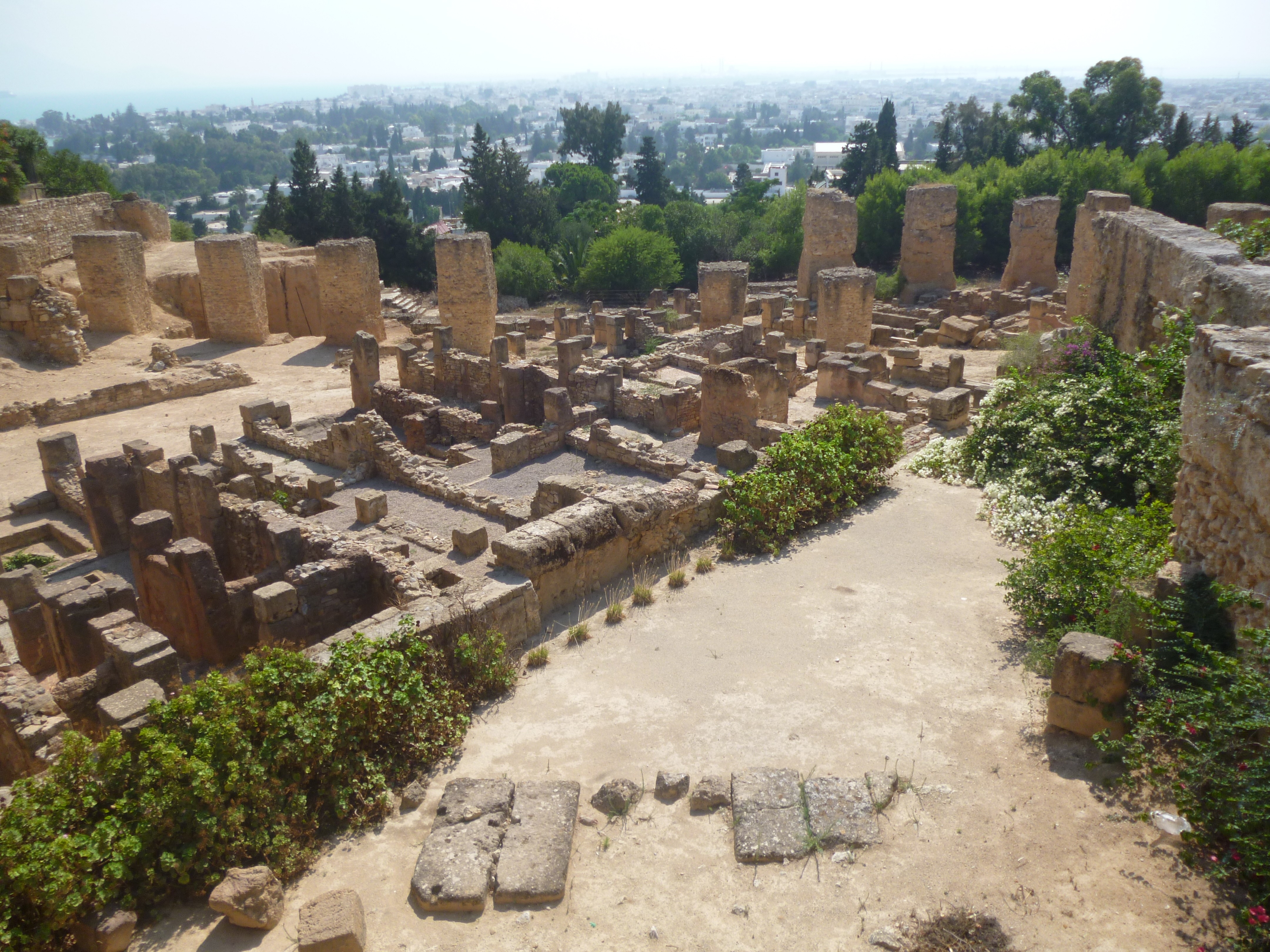

Site archéologique de Carthage (Tunisie)

Saints Lucius, Montanus

et leurs compagnons, martyrs à Carthage (✝ 259)

Lucius, Montanus, Julien et Victoric étaient disciples

de saint Cyprien et

appartenaient presque tous au clergé. Ils furent rendus responsables de

désordres provoqués dans la ville et pour cette raison furent mis à mort.

À Carthage, en 259, les saints martyrs Lucius, Montan, Julien et Victoric. Sous

l’empereur Valérien, ils furent décapités pour la religion et la foi que saint

Cyprien leur avait enseignées. Avec eux sont commémorés saint Victor, prêtre,

martyrisé avant eux, et saint Donatien, mort en prison.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1208/Saints-Lucius--Montanus.html

Dans l'Afrique

proconsulaire, la mort de saint Cyprien donna le signal de la persécution. Le

proconsul ayant provoqué une émeute par sa férocité, affecta, comme jadis

Néron, d'y voir l'ouvrage des chrétiens. Parmi les victimes se trouve un groupe

de martyrs dont nous avons des actes très curieux et dignes de toute confiance,

mais dans lesquels, comme dans ceux de Jacques et Marien, le mauvais goût

littéraire du temps a prodigué l'obscurité et la déclamation. Nous n'avons pas

pensé que ces taches, qui peuvent intéresser vivement dans l'étude de

l'original, dussent être reproduites dans la présente traduction. M. de Rossi a

rapproché une phrase de la lettre écrite par les martyrs à leurs « frères » de

quatre vers hexamètres du poète Commodien qu'ils citaient fort exactement.

BOLL. 24/III, 454-459. RUINART, Act. sinc. p.132 et suiv. —

DE ROSSI, Inscript. christ. Urb. Rom. t. II, p. XXXII. — P.

ALLARD, Hist. des persec. III, 116 et suiv. — DE ROSSI, Bullett. di arch. crist. (1880), p. 66-68. — TILLEMONT, Mém. IV, 206-14, 647-9. — PIO FRANCHI DE CAVALIERI, Gli

atti dei SS. Montano, Lucio e compagni, dans Romische

Quartalschrift., VIII,1898, et Anal. boll., 1899, p. 67.

Nous vous

envoyons, frères bien-aimés, le récit de nos combats ; car des serviteurs de

Dieu, consacrés à son Christ, n'ont pas d'autre devoir que de penser à leurs

nombreux frères. C'est une raison de fraternelle tendresse et de charité qui

nous a portés à vous envoyer ces lettres, afin que les frères qui viendront

après nous y trouvent un témoignage fidèle de la magnificence de Dieu, de nos

travaux et de nos souffrances pour lui.

A la suite de

l'émeute qu'excita la férocité du pro-consul, et de la persécution qui vint

aussitôt après, nous, Lucius, Montan, Flavien, Julien, Victor, Primole, Renon

et Donatien, nous fumes arrêtés. Donatien n'était encore que catéchumène, il

fut baptisé dans la prison et mourut aussitôt, passant ainsi du baptême au

martyre. Primole eut la même fin. Toutefois on n'eut pas le temps de lui

administrer le sacrement, sa confession lui en tint lieu.

Dès que l'on

nous eut pris, nous fûmes confiés à la garde des magistrats municipaux; nos

gardes nous dirent que le proconsul voulait nous faire brûler vifs dès le

lendemain. Mais le Seigneur, à qui seul appartient de garder ses disciples de

la flamme et entre les mains de qui sont les ordres et la volonté du prince,

détourna de nous la cruauté du proconsul, et, par nos prières incessantes, nous

obtînmes ce que nous demandions dans l'ardeur de notre foi; le feu déjà presque

allumé pour nous consumer fut éteint et la flamme des bûchers embrasés fut

étouffée par la rosée divine.

Eclairés par

les promesses que le Seigneur a faites par son Saint-Esprit, les fidèles

croiront sans peine que les miracles récents égalent ceux d'autrefois, car le

Dieu qui avait fait éclater sa gloire dans les trois enfants, triomphait de

même en nous. Ainsi donc, — Dieu aidant, — le proconsul, revenu de son dessein,

donna ordre de nous conduire dans les prisons. Nous y fûmes menés par une garde

de soldats et nous nous montrâmes assez peu soucieux de l'obscurité fétide de

notre nouveau séjour. Bientôt la prison toute noire fut éclairée des feux du

Saint-Esprit, et au lieu des fantômes de l'obscurité et

des ignorances aveugles qu'apporte la nuit, la foi nous revêtit d'une lumière

semblable à celle du jour, et nous descendions dans la geôle la plus

douloureuse comme nous serions montés au ciel.

Les mots nous

manquent pour dire quels jours et quelles nuits nous passâmes en ce lieu.

L'imagination se refuse à concevoir l'horreur de ce cachot, et la parole ne

peut suffire à en décrire les souffrances. Mais la gloire de celui qui triomphe

en nous se mesure à l'épreuve elle-même : ce n'est pas nous qui combattons, la

victoire est à celui qui combat pour nous. Qu'importe la mort au fidèle, cette

mort dont le Seigneur a triomphé par sa croix, dont il a émoussé l'aiguillon et

fait, par son supplice, évanouir l'horreur? Mais on ne parle d'armes que pour

le soldat, et le soldat lui-même ne s'arme que pour le combat ; ainsi nos couronnes

ne sont une récompense que parce qu'il y a eu combat : on donne les prix à la

fin des jeux.

Pendant

plusieurs jours nous fûmes réconfortés par la visite des frères, de sorte que

la joie et la consolation des jours faisait oublier l'horreur des nuits.

Renon, l'un de

nous, eut une vision pendant son sommeil. C'étaient des hommes qu'on menait

mourir. devant chacun desquels on portait une lampe ; ceux qu'une lampe ne

précédait pas étaient abandonnés. Il nous ,vit marcher précédés de nos lampes ;

sur ces entrefaites, il s'éveilla. Quand Renon nous raconta sa vision, nous

fûmes bien heureux, nous savions maintenant que nous étions dans le bon chemin,

nous marchions avec le Christ, lumière de nos pas et Verbe de Dieu.

Après une

telle nuit, on passait le jour dans la joie. Précisément, ce matin-là, nous

fûmes subitement traduits devant le procurateur, qui faisait l'intérim du

proconsul, mort depuis peu.

O jour de joie ! ô

glorieux liens ! ô chaînes désirées ! ô fers plus glorieux et plus précieux que

l'or ! ô bruit des anneaux qui sursautent sur le pavé ! Nous parlions de

l'avenir et de peur que notre félicité ne fût retardée, les soldats, ne sachant

où le procurateur voulait nous entendre, nous menèrent dans tout le Forum ;

enfin nous fûmes appelés dans son cabinet.

Mais l'heure

de mourir n'était pas arrivée. Ayant vaincu le diable, nous fûmes renvoyés en

prison ; l'on nous réservait à une autre victoire. Vaincu cette fois, le diable

combina de nouvelles embûches, il tenta de nous vaincre par la faim et la soif.

Cette nouvelle épreuve se prolongea longtemps, et nos corps épuisés

n'obtenaient même pas un peu d'eau froide de Solon, l'économe.

Cette fatigue,

ces privations, ce temps de misère étaient permis de Dieu, car celui qui voulut

que nous fussions éprouvés, montra qu'il voulait nous parler au sein même de

l'épreuve. Voici donc ce que le prêtre Victor apprit dans une vision qui

précéda de peu d'instants son martyre. Il nous l'a racontée ainsi : « Je voyais

un enfant entrer dans cette prison; son visage était resplendissant au delà de

ce que l'on peut dire; il nous conduisait à toutes les portes, comme pour nous

rendre à la liberté, mais nous ne pouvions sortir. Il me dit alors : « Encore

quelques jours de souffrance, puisque vous êtes retenus ici, mais ayez confiance,

je suis avec vous ». Il reprit : « Dis-leur que leurs couronnes seront d'autant

plus glorieuses, car l'esprit vole vers son Dieu et l'âme près de souffrir

aspire aux demeures qui l'attendent ». Connaissant que c'était le Seigneur,

Victor demanda où était le Paradis. « Hors du monde », dit l'enfant.— «

Montrez-le-moi. » — « Et où serait la foi? » dit encore l'enfant. Par un reste

de faiblesse humaine, le prêtre dit : « Je ne puis m'acquitter de l'ordre que

vous m'avez donné : laissez-moi un signe qui serve de témoignage à mes frères

».

L'enfant répondit :

« Dis-leur que mon signe est le signe de Jacob ». Maintenant voici ce qui a

trait à notre compagne de captivité, la matrone Quartillosa, dont le mari et le

fils avaient été martyrisés trois jours auparavant, et qui ne devait pas tarder

à les suivre. Elle nous a raconté sa vision en ces termes : « Je vis mon enfant

martyr venir à la prison et il s'assit au bord de l'eau; il me dit : « Dieu

voit votre angoisse et votre souffrance ». Alors entra un jeune homme d'une

taille extraordinaire, portant dans chaque main une coupe de lait ; il me dit :

« Courage, Dieu tout-puissant s'est souvenu de vous ». Et il donna à boire à

tous les prisonniers, mais il n'y paraissait pas, ses coupes ne diminuaient pas.

Soudain la pierre qui bouchait la moitié de la fenêtre du cachot sembla

s'écrouler, laissant voir un coin de ciel; le jeune homme posa les coupes à

droite et à gauche : « Vous voilà rassasiés, dit-il; cependant les coupes sont

encore pleines et même l'on va vous en apporter une troisième ».

Il disparut.

Le lendemain,

nous étions dans l'attente de l'heure où l'administrateur de la prison nous

ferait porter, non la nourriture, il ne nous en donnait plus et depuis deux

jours nous n'avions rien mangé, mais de quoi sentir notre souffrance et notre

privation, lorsque tout à coup, ainsi que la boisson arrive à celui qui est

altéré, la nourriture à l'affamé, le martyre à celui qui le demande, de même le

Seigneur nous réconforta par l'intermédiaire du prêtre Lucien qui, forçant

toutes les consignes, nous envoya deux coupes, par l'entremise de Hérennien,

sous-diacre, et Janvier, catéchumène, qui portèrent à chacun l'aliment qui ne

diminue pas. Ce secours soutint les malades et les infirmes ; ceux-là mêmes que

la férocité de Solon et le manque d'eau avaient rendus malades, furent guéris,

ce dont tous rendirent à Dieu de grandes actions de grâces.

Il est temps de

dire quelque chose de la tendresse mutuelle que nous nous portions.

Montan avait

eu avec Julien d'assez vives discussions au sujet d'une femme exclue de la

communion, qui s'y fit recevoir par surprise. La dispute finie, une certaine

froideur ne laissa pas que de subsister entre les confesseurs ; mais, la nuit

suivante, Montan eut une vision. La voici telle qu'il l'a racontée : « Je vis

des centurions venir à nous, ils nous conduisirent, après une longue traite,

dans une plaine immense où Cyprien et Lucius vinrent à nous. Une blanche

lumière baignait la campagne, nos propres vêtements étaient blancs, notre chair

plus blanche que nos vêtements. A travers la chair transparente les regards

pénétraient jusqu'au coeur. Je regardais ma poitrine, il y avait des taches. A

ce moment je m'éveillais et Lucius entrait. Je lui racontai la vision : «

Sais-tu, ajoutai je, d'où viennent ces tâches ? De ce que je ne me suis pas

tout de suite réconcilié avec Julien. J'en conclus, frères très chers, que nous

devons mettre tous nos soins à conserver la concorde, la paix, l'entente entre

nous. Efforçons-nous d'être dès ce monde tels que nous serons dans l'autre. Si

les récompenses promises aux justes nous attirent, si le châtiment réservé aux

impies nous épouvante, si nous souhaitons vivre et régner avec le Christ,

faisons ce qui y conduit. Adieu. »

Ce qui précède

fut écrit par les martyrs dans leur prison, mais il était indispensable que

quelqu'un recueillît de ce martyre tout ce que la modestie des confesseurs

s'ingéniait à tenir secret. Flavien m'a confié la charge de suppléer à tout ce

qu'ils avaient omis ; j'ai donc ajouté ce qui suit :

Après

plusieurs mois d'une détention pendant laquelle ils souffrirent de la faim et

de la soif, tous les confesseurs :furent amenés un soir devant le nouveau

proconsul.

Tous confessèrent le Christ.

Flavien s'était déclaré diacre, mais ses amis présents déclarèrent, poussés par

une affection intempestive, qu'il n'avait pas cette qualité.

Quant à

Lucius, Montan, Julien, Victor, ils furent condamnés sur-le-champ. Flavien fut

ramené en prison. Encore qu'il eût tout sujet de s'affliger d'être séparé d'une

compagnie si sainte, cependant sa foi et sa charité étaient si profondes qu'il

n'y voulut voir que la volonté de Dieu. Ainsi sa piété modérait son chagrin.

Pendant que Flavien regagnait la prison, les condamnés se rendaient au lieu des

exécutions. Une cohue énorme, où les chrétiens roulaient pêle-mêle avec les

païens, suivait les martyrs. Les fidèles en avaient vu un grand nombre déjà,

mais jamais avec autant d'émotion et de respect. Le visage des victimes rayonnait

de bonheur, leurs paroles étaient brûlantes et fortifiaient les fidèles.

Lucius, naturellement doux et timide, épuisé par ses infirmités et le séjour de

la prison, avait pris les devants avec quelques amis, car il craignait d'être

étouffé dans les remous de la foule et de perdre l'occasion de répandre son

sang. Pendant le trajet, il s'entretenait avec ses compagnons et ne laissait

pas de les instruire. Ceux-ci lui disaient : « Vous vous souviendrez de

nous ! » — « C'est à vous, répondit-il, à vous souvenir de moi » ; car son

humilité était si profonde qu'à cet instant même il ne se prévalait pas de son

martyre. Julien et Victor recommandaient aux frères avec instances la concorde,

le soin des clercs, de ceux-là surtout qui souffraient en prison les horreurs

de la faim. Joyeux et calmes, les confesseurs arrivaient au lieu du supplice.

Montan était

de haute taille, intrépide et habitué jusqu'alors à dire toute sa pensée sans

ménagement. Exalté par la perspective du martyre tout proche, il criait à

pleine voix « Quiconque sacrifiera à d'autres qu'au seul Dieu sera anéanti ».

Et il répétait sans se lasser qu'il n'est pas permis de déserter l'autel de

Dieu pour s'adresser aux idoles fabriquées. Il s'adressait ensuite aux

hérétiques : « Que la multitude des martyrs, leur disait-il, vous apprenne où

est la véritable Eglise, celle dans laquelle vous devez entrer ». Aux apostats

il rappelait que la communion ne leur serait accordée qu'après la pénitence. A

ceux qui n'avaient pas faibli il disait: « Tenez ferme, frères, combattez avec

courage. Les exemples ne vous manquent pas. Que la lâcheté de ceux qui sont

tombés ne vous entraîne pas dans leur ruine ; loin de là, que nos souffrances

vous excitent à gagner la couronne ». Apercevant des vierges chrétiennes, il adressa

la parole à chacune d'elles, les exhortant à garder la chasteté. A tous les

fidèles il recommanda d'obéir aux prêtres ; aux prêtres il demanda de garder

entre eux la bonne entente qui,disait-il, est préférable à tout. De l'exemple

qu'ils en donneront, dépendront l'obéissance et l'affection du peuple envers

eux. Voilà qui est vraiment souffrir pour le Christ et le reproduire par

l'action et par la parole. Quel exemple pour le fidèle !

Le bourreau était

prêt, sa longue épée déjà suspendue sur le cou des condamnés, lorsqu'on vit

Montan lever les bras au ciel, et, tout haut, de manière à être entendu des

païens et des chrétiens, il demanda à Dieu que Flavien, séparé de ses

compagnons par l'ordre du peuple, les suivit dans trois jours. Et comme pour

donner un gage que sa prière était exaucée, il déchira en deux morceaux le

bandeau mis sur ses yeux et prescrivit qu'on en gardât la moitié pour servir à

Flavien. Enfin il recommanda de réserver la place de celui-ci entre leurs

tombeaux,afin que la mort au moins lui rendît leur compagnie. Nous avons vu de

nos yeux s'accomplir la promesse faite par le Seigneur dans l'Évangile, que

rien ne sera refusé à une demande inspirée par une foi vive. Deux jours après,

Flavien fut exécuté.

Comme je l'ai

dit, Montan ne voulait pas que le retard imposé à Flavien le séparât de leur

compagnie dans le tombeau ; il me faut maintenant raconter sa fin.

A la suite des

réclamations qui s'étaient produites à son sujet, Flavien avait été ramené en

prison ; il était fort, intrépide et confiant. Son malheur n'avait pu entamer

la trempe de son âme. Un autre peut-être eût été ébranlé ; quant à lui, la foi

qui l'avait précipité vers le martyre, lui faisait mépriser tous les obstacles

humains.

Son admirable

mère, qui, digne par sa foi des anciens patriarches, rappelait ici Abraham

lui-même impatient d'immoler son fils, se désolait que Flavien eût perdu la

gloire du martyre. Quelle mère ! Quel modèle ! elle était digne d'être la

mère des Macchabées, car qu'importe le nombre ? puisqu'elle offrait à Dieu

l'unique objet de son amour.

Mais Flavien

lui disait : « Mère que j'aime tant, j'avais souvent désiré confesser le

Christ, rendre mon témoignage, porter des chaînes, et jamais cela n'arrivait.

Aujourd'hui mon désir est accompli; rendons gloire au lieu de gémir ».

Quand les

geôliers vinrent, ils eurent peine à ouvrir la porte malgré leurs efforts ; il

semblait que la prison elle-même répugnait à recevoir un hôte déjà marqué pour

le ciel ; mais comme ce sursis était dans les desseins de Dieu, le cachot,

quoique à regret, reçut son hôte. Que dire des sentiments de Flavien pendant

ces deux jours ? son espérance, sa confiance dans l'attente du martyre ?

Le troisième jour sembla non celui de la mort, mais celui de la résurrection.

Les païens, qui avaient entendu la prière de Montan, ne cachaient plus leur

admiration.

Dès que l'on

sut donc, le troisième jour, que Flavien allait mourir, tous les mécréants et

impies se rendirent au prétoire,afin de voir comment il se comporterait.

Il sortit

enfin de cette prison où il ne devait plus rentrer. Quand il parut , la joie

fut grande parmi les spectateurs, mais lui-même était plus joyeux encore,

assuré que sa foi et la prière d'autrui lui procureraient le martyre, quelque

opposition qu'on y fît. Aussi disait-il à tous les frères qui venaient le

saluer qu'il leur donnerait la paix dans les plaines de Fuscium. Quelle

confiance ! quelle foi !

Enfin il pénétra

dans le prétoire et attendit son tour d'appel dans la salle des gardes. J'étais

à côté de lui, ses mains dans les miennes, rendant au martyr l'honneur et les

soins dus à un ami intime. Ses anciens élèves l'importunaient afin qu'il

renonçât à son obstination et qu'il sacrifiât; on l'eût laissé faire ensuite

tout ce qu'il eût voulu. « Il faut être fou, disaient-ils, pour ne pas craindre

la mort et avoir peur de vivre. »

Flavien les remerciait d'une

affection qu'ils témoignaient à leur manière et des conseils qu'elle lui valait

; cependant il reprenait : «Sauver la liberté de sa conscience vaut mieux

qu'adorer des pierres. Il n'y a qu'un seul Dieu, qui a tout fait et à qui seul

est dû notre culte ». Il disait encore d'autres choses dont les païens

convenaient malaisément : « Même quand on nous tue, nous vivons, disait-il ;

nous ne sommes pas vaincus, mais vainqueurs de la mort ; et vous-mêmes, si vous

voulez savoir la vérité, soyez chrétiens ».

Reçus de la

sorte, les païens, voyant que la persuasion ne réussissait pas, usèrent d'une

étrange miséricorde à l'égard de Flavien : ils s'imaginèrent que la torture

viendrait à bout de sa résistance. On le mit sur le chevalet et le proconsul

lui demanda pourquoi il prenait indûment la qualité de diacre : « Je ne mens

pas, dit-il je le suis ». Un centurion apporta un certificat qui prouvait le

contraire. « Pouvez-vous croire que je mente, dit Flavien, et que l'auteur de

cette fausse pièce dise vrai ? » Le peuple brailla: « Tu mens ». Le

proconsul revint à la charge et lui demanda s'il mentait ; il répondit :

« Quel intérêt aurais-je à mentir ? » Le peuple, exaspéré, hurlait : « La

torture, la torture ! » Mais Dieu savait assez, depuis l'épreuve de la

prison, la fermeté de son serviteur ; il ne permit pas que le corps du martyr

déjà éprouvé fût déchiré. Flavien fut condamné à être décapité.

Maintenant qu'il

était sûr de mourir, Flavien marchait plein de joie et causait avec une extrême

liberté à ceux qui l'entouraient. Ce fut alors qu'il me chargea d'écrire

l'histoire de tout ce qui s'était passé. Il tenait en outre à ce que le récit

des visions qui avaient occupé ses deux derniers jours fût consigné avec

quelques autres plus anciennes.

« Peu après la

mort de saint Cyprien, nous raconta-t-il, il me sembla que je causais avec lui,

et je lui demandai si le coup de la mort est bien douloureux, — futur martyr,

ces questions m'intéressaient . — Il me répondit : « Ce n'est plus notre chair

qui souffre quand l'âme est au ciel. Le corps ne sent plus quand l'esprit

s'abandonne tout entier à Dieu. Plus tard, ajouta-t-il, après le supplice de

mes compagnons, je me sentais sous le coup d'une grande tristesse, à la pensée

que je demeurais seul ; mais pendant mon sommeil je vis un homme qui me dit : «

Pourquoi t'affliges-tu ? » Je lui dis le sujet de mon chagrin. — « Quoi !

reprit-il, te voilà triste, toi qui, deux fois confesseur, seras demain martyr

par le glaive ? » Et ceci arriva de point en point. Après une première

confession dans le cabinet du proconsul, et une autre en public, il fut

reconduit en prison, puis, traduit de nouveau, il confessa encore et mourut. Il

nous raconta une autre vision, qui eut lieu le lendemain de la mort de Successus

et de Paul. « Je vis, dit-il, l'évêque Successus qui entrait dans ma maison,le

visage radieux, mais à peine reconnaissable à cause de l'éclat céleste dont

brillaient ses yeux. Cependant je le reconnus et il me dit : « J'ai été envoyé

pour t'annoncer que tu souffriras ». Aussitôt deux soldats m'emmenèrent en un

lieu où une multitude de frères étaient assemblés. On me conduisit au juge, qui

me condamna à mort. Soudain ma mère se montra dans la foule: « Vivat, vivat !

disait-elle, il n'y a pas eu de martyre plus glorieux ». Elle disait vrai ;

car, outre les privations de la prison, imaginées par la rapacité

du fisc, Flavien savait encore se

priver du peu qu'on lui donnait, tant il aimait à pratiquer les jeûnes

prescrits et à s'abstenir du nécessaire pour en faire part à autrui.

J'en viens aux

circonstances de son martyre. Tout en parlant, Flavien habitait déjà en esprit

? dans le royaume où, dans peu d'instants, il devait régner avec Dieu ; ses

entretiens en avaient la dignité sereine. Le ciel lui-même avait pris parti

pour nous. Une pluie torrentielle avait dispersé la foule, les païens curieux

étaient partis,comme pour laisser le champ libre aux consolations et afin que

nul profane ne fût témoin du suprême baiser de paix. Flavius remarqua que la

pluie semblait tomber afin que l'eau et le sang fussent mélangés,ainsi qu'il

arriva dans la passion du Sauveur.

Après qu'il

eut fortifié chacun et donné le baiser, il quitta l'étable où il avait cherché

un abri et qui touche au domaine de Fuscium et monta sur un pli de terrain ;

d'un geste il réclama le silence : « Frères bien-aimés, dit-il, vous avez la

paix avec nous si vous restez en paix avec l'Église ; gardez l'union dans la

charité. Ne méprisez pas mes paroles : Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ lui-même,

peu avant sa passion, a dit: « Je vous laisse le commandement de vous aimer les

uns les autres ». Il termina donnant à ses dernières paroles l'apparence d'un

testament par lequel il désignait le prêtre Lucien comme le plus capable, à ses

yeux, d'occuper le siège de saint Cyprien. Puis il descendit à l'endroit où il

devait mourir, se lia le bandeau laissé par Montan à cette intention, se mit à

genoux et mourut pendant sa prière.

Oh ! qu'ils

sont glorieux les enseignements des martyrs ! qu'elles sont nobles les épreuves

qu'ont subies les témoins de Dieu ! C'est avec raison que l'Écriture les

transmet aux générations à venir ; car, si nous trouvons dans l'étude des

ouvrages anciens de précieux exemples, il convient que les saints qui ont

fleuri de nos jours deviennent également nos maîtres.

Les Martyrs, TOME

II. Le Troisième Siècle. Dioclétien. Recueil de pièces authentiques sur les

martyres depuis les origines du christianisme jusqu'au XXe siècle. Traduites et publiées par le B. P. DOM H. LECLERCQ, Moine bénédictin de

Saint-Michel de Farnborough. Imprimi potest, FR. FERDINANDUS CABROL, Abbas Sancti Michaelis Farnborough. Die 15 Martii 1903. Imprimatur. Pictavii, die 24 Martii 1903. + HENRICUS, Ep. Pictaviensis.

Montanus, Lucius & Companions MM (RM)

Died 259. Montanus, Lucius, Julian, Victoricus, Flavian, Rhenus, and two

companions were a group of African martyrs. Several of them were clergy of

Saint Cyprian, who had been executed the previous year under Valerian. Their

acta are thoroughly authentic: the first part of their acts- -their

imprisonment--was written down by themselves, and that of their martyrdom by

eyewitnesses.

After Cyprian's

martyrdom, the proconsul Galerius Maximus died. Solon, the procurator,

continued the persecution while awaiting the arrival of a new proconsul from

Rome. The citizens of Carthage rose up against Solon's tyranny, but instead of

seeking to discover the culprits, Solon vented his fury upon the Christians,

knowing this would be agreeable to the idolaters.

Eight disciples of

Saint Cyprian were arrested on a false charge of complicity in the revolt.

After interrogation they were remanded to custody; they were kept on short

rations, and suffered greatly from hunger and thirst. One of them writes:

"As soon as we

were taken, we were given in custody to the officers of the quarter: when the

governor's soldiers told us that we should be condemned to the flames, we

prayed to God with great fervor to be delivered from that punishment and He in

whose hands are the hearts of men, was pleased to grant our request. The

governor altered his first intent, and ordered us into a very dark and

incommodious prison, where we found the priest, Victor and some others, but we

were not dismayed at the filth and darkness or the place, our faith and joy in

the Holy Ghost reconciled us to our sufferings in that place, though these were

such as it is not easy for words to describe; but the greater our trials, the

greater is He who overcomes them in us.

"Our brother

Rhenus in the mean time, had a vision, in which he saw several of the prisoners

going out of prison with a lighted lamp preceding each of them, while others,

that had no such lamp, stayed behind. He discerned us in this vision, and

assured us that we were of the number of those who went forth with lamps. This

gave us great joy; for we understood that the lamp represented Christ, the true

light, and that we were to follow Him by martyrdom.

"The next day

we were sent for by the governor, to be examined. It was a triumph to us to be

conducted as a spectacle through the market-place and the streets, with our

chains rattling. The soldiers, who knew not where the governor would hear us,

dragged us from place to place, till, at length, he ordered us to be brought

into his closet.

"He put several

questions to us; our answers were modest, but firm: at length we were remanded

to prison; here we prepared ourselves for new conflicts. The sharpest trial was

that which we underwent by hunger and thirst, the governor having commanded

that we should be kept without meat and drink for several days, inasmuch that

water was refused us after our work: yet Flavian, the deacon, added great

voluntary austerities to these hardships, often bestowing on others that little

refreshment which was most sparingly allowed us at the public charge.

"God was

pleased Himself to comfort us in this our extreme misery, by a vision which He

vouchsafed to the priest Victor, who suffered martyrdom a few days after. 'I

saw last night,' said he to us, 'an infant, whose countenance was of a

wonderful brightness, enter the prison. He took us to all parts to make us go

out, but there was no outlet; then he said to me, "You have still some

concern at your being retained here, but be not discouraged. I am with you:

carry these tidings to your companions, and let them know that they shall have

a more glorious crown."

"'I asked him

where heaven was; the infant replied, "Out of the world." Show it

me,' says Victor. The infant answered, "Where then would be your

faith?" Victor said, 'I cannot retain what you command me: tell me a sign

that I may give them.' He answered, "Give them the sign of Jacob, that is,

his mystical ladder, reaching to the heavens."' Soon after this vision,

Victor was put to death. This vision filled us with joy.

"God gave us,

the night following, another assurance of His mercy by a vision to our sister

Quartillosia, a fellow-prisoner, whose husband and son had suffered death for

Christ three days before, and who followed them by martyrdom a few days after.

'I saw,' says she, 'my son, who suffered; he was in the prison sitting on a

vessel of water, and said to me: "God has seen your sufferings." Then

entered a young man of a wonderful stature, and he said "Be of good

courage, God hath remembered you."'"

The martyrs had received

no nourishment the preceding day, nor had they any on the day that followed

this vision; but at length Lucian, then priest, and afterwards bishop of

Carthage, surmounting all obstacles, got food to be carried to them in

abundance by the subdeacon, Herennian, and by Januarius, a catechumen. The acta

say they brought the never-failing food, the Blessed Eucharist.

The acta continue:

"We have all

one and the same spirit, which unites and cements us together in prayer, in

mutual conversation, and in all our actions. These are those amiable bands

which put the devil to flight, are most agreeable to God, and obtain of Him, by

joint prayer, whatever they ask. These are the ties which link hearts together,

and which make men the children of God. To be heirs of His kingdom we must be

His children, and to be His children we must love one another. It is impossible

for us to attain to the inheritance of His heavenly glory, unless we keep that

union and peace with all our brethren which our heavenly Father has established

among us.

"Nevertheless,

this union suffered some prejudice in our troop, but the breach was soon

repaired. It happened that Montanus had some words with Julian, about a person

who was not of our communion, and who was got among us, (probably admitted by

Julian). Montanus on this account rebuked Julian, and they, for some time

afterwards, behaved towards each other with coldness, which was, as it were, a

seed of discord.

"Heaven had

pity on them both, and, to reunite them, admonished Montanus by a dream, which

he related to us as follows: 'It appeared to me that the centurions were come

to us, and that they conducted us through a long path into a spacious field,

where we were met by Cyprian and Lucius. After this we came into a very

luminous place, where our garments became white, and our flesh became whiter

than our garments, and so wonderfully transparent, that there was nothing in

our hearts but what was clearly exposed to view: but in looking into myself, I

could discover some filth in my own bosom; and, meeting Lucian, I told him what

I had seen, adding, that the filth I had observed within my breast denoted my

coldness towards Julian. Wherefore, brethren, let us love, cherish, and

promote, with all our might, peace and concord. Let us be here unanimous in

imitation of what we shall be hereafter. As we hope to share in the rewards

promised to the just, and to avoid the punishments wherewith the wicked are

threatened: as, in the end, we desire to be and reign with Christ, let us do

those things which will lead us to him and his heavenly kingdom.'"

Hitherto the

martyrs wrote in prison what happened to them there: the rest was written by

those persons who were present, to whom Flavian, one of the martyrs, had

recommended it. Their imprisonment lasted several months, and then those in

holy orders were condemned to death because the edict of Valerian condemned

only bishops, presbyters, and deacons.

Because of his

popularity, the false friends of Flavian maintained before the judge that he

was no deacon, and, consequently, was not included within the emperor's decree.

Though Flavian declared himself to be one, he was not then condemned; but the

rest were adjudged to die. They walked cheerfully to the place of execution,

and each of them gave exhortations to the people.

Lucius went to the

place of execution in advance, being so enfeebled that he feared he could not

keep up with the others; but Montanus was full of vigor and exhorted the

heathen among the bystanders to repentance and the brethren to faithfulness:

"He that

sacrificeth to any God but the true one, shall be utterly destroyed." He

also checked the pride and wicked obstinacy of the heretics, telling then that

they might discern the true church by the multitude of its martyrs. He exhorted

those that had fallen not to be over hasty, but fully to accomplish their

penance. He exhorted the virgins to preserve their purity, and to honor the

bishops, and all the bishops to abide in concord.

When the

executioner was ready to give the stroke, Montanus prayed aloud to God that

Flavian who had been reprieved at the people's request, might follow them on

the third day. And, to express his assurance that his prayer was heard, he

ripped in half the handkerchief with which his eyes were to be covered, and

asked that one part of it to be reserved for Flavian, and desired that a place

might be kept for him where he was to be interred, that they might not be

separated even in the grave.

Flavian, seeing his

crown delayed, made it the object of his ardent desires and prayers. He

continued to insist that he was a deacon, and so he was beheaded three days

later (Attwater, Benedictines, Husenbeth).

Saint of the Day: Sts. Montanus and Lucius and their

Companions

“We have all one and the same spirit”

Martyrs (d. 259)

Their story

+ In the year 259, the Roman procurator Solon arrested

eight Christians following an uprising in Carthage in North Africa. Although

the Christian community was not connected to the insurgence, Solon used this as

an excuse for persecuting Christians.

+ Many of those arrested were clergy serving Saint

Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage.

+ After being imprisoned for several months, during

which time they were deprived of food and water, each of the martyrs died after

having spoken to the crowds, especially urging those who have denied their

faith in Christ to return to the Church.

+ Only the names of the two of the martyrs—the priest

Lucius and a layman named Montanus—have come down to us.

+ Saints Montanus, Lucius, and companions died in the

year 250. Devotion to the martyrs spread quickly throughout the Christian world

and the historic account of their martyrdom is considered to be authentic.

For prayer and reflection

“We have all one and the same spirit which unites and

cements us together in prayer, in mutual intercourse, and in all actions. These

are the bonds of affection which put the devil to flight, which are most

pleasing to God… It is impossible for us to attain the inheritance of heavenly

glory unless we keep that union and peace with our brothers which our heavenly

Father has established among us.”—Saint Lucius

Prayer

O God, from whom faith draws perseverance and weakness

strength, grant, through the example and prayers of the Martyrs Montanus,

Lucius and their companions, that we may share in the Passion and Resurrection

of your Only Begotten Son, so that with the Martyrs we may attain perfect joy

in your presence. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns

with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

(from The Roman Missal: Common of Martyrs—For

Several Martyrs During the Easter Season)

Saint profiles prepared by Brother Silas Henderson,

S.D.S.

SOURCE : https://aleteia.org/daily-prayer/saturday-may-23/

Montanus, Lucius, Flavian, Julian, Victoricus &

Companions

St Montanus (Died 259) was a disciple of St Cyprian, a

lawyer and then Bishop of Carthage in Tunisia.

In 258, St Cyprian was martyred on the orders of

Galerius Maximus by the sword; the reason, spreading Christianity and

refusing to offer deities to pagan gods. The soldier who executed St Cyprian

died soon afterwards and a replacement soldier was ambushed and killed by

rebels. In revenge, eight Christians, a mixture of lay people, Priests and

Bishops, including St Montanus, St Lucius, St Flavian, St Julian and St

Victoricus were selected at random for execution by beheading.

On the day of their execution, St Montanus, who had

lived a hermit lifestyle, spoke to the gathered crowd, probably a large number

of them peasant Christians. He said, hold dear to your faith, live the life

Jesus asked and never forget Jesus’ promise namely, “Your reward will be great

in heaven”.

All eight martyrs accepted their torture and execution

by beheading rather than renounce their Christian faith. Their Feast Day is

24th February.

St Montanus & Companions:

Pray for us that we will never forget Jesus’ promise,

“Your reward will be great in Heaven”.

Glory be to the…

SOURCE : https://www.daily-prayers.org/saints-library/montanus-companions/

SS. Montanus,

Lucius, Flavian, Julian, Victoricus, Primolus, Rhenus, and Donatian, Martyrs at

Carthage

From their

original acts, written, the first part by the martyrs themselves, the rest by

an eye-witness. They are published more correctly by Ruinart than by Surius and

Bollandus. See Tillemont, t. 4. p. 206.

A.D. 259

THE PERSECUTION,

raised by Valerian, had raged two years, during which, many had received the

crown of martyrdom, and, amongst others, St. Cyprian, in September, 258. The

proconsul Galerius Maximus, who had pronounced sentence on that saint, dying

himself soon after, the procurator, Solon, continued the persecution, waiting

for the arrival of a new proconsul from Rome. After some days, a sedition was

raised in Carthage against him, in which many were killed. The tyrannical man,

instead of making search after the guilty, vented his fury upon the Christians,

knowing this would be agreeable to the idolaters. Accordingly he caused these

eight Christians, all disciples of St. Cyprian, and most of them of the clergy,

to be apprehended. As soon as we were taken, say the authors of the acts, we

were given in custody to the officers of the quarter: 1 when the governor’s soldiers told us that we should be condemned to the

flames, we prayed to God with great fervour to be delivered from that

punishment: and he, in whose hands are the hearts of men, was pleased to grant

our request. The governer altered his first intent, and ordered us into a very

dark and incommodious prison, where we found the priest, Victor, and some

others: but we were not dismayed at the filth and darkness of the place, our

faith and joy in the Holy Ghost reconciled us to our sufferings in that place,

though these were such as it is not easy for words to describe; but the greater

our trials, the greater is he who overcomes them in us. Our brother Rhenus, in

the mean time, had a vision, in which he saw several of the prisoners going out

of prison with a lighted lamp preceding each of them, whilst others, who had no

such lamp stayed behind. He discerned us in this vision, and assured us that we

were of the number of those who went forth with lamps. This gave us great joy;

for we understood that the lamp represented Christ, the true light, and that we

were to follow him by martyrdom.

The next day we

were sent for by the governor, to be examined. It was a triumph to us to be

conducted as a spectacle through the market-place and the streets, with our

chains rattling. The soldiers, who knew not where the governor would hear us,

dragged us from place to place, till, at length, he ordered us to be brought

into his closet. He put several questions to us; our answers were modest, but

firm: at length we were remanded to prison; here we prepared ourselves for new

conflicts. The sharpest trial was that which we underwent by hunger and thirst,

the governor having commanded that we should be kept without meat and drink for

several days, insomuch that water was refused us after our work: yet Flavian,

the deacon, added great voluntary austerities to these hardships, often

bestowing on others that little refreshment which was most sparingly allowed us

at the public charge.

God was pleased

himself to comfort us in this our extreme misery, by a vision which he

vouchsafed to the priest Victor, who suffered martyrdom a few days after. “I

saw last night,” said he to us, “an infant, whose countenance was of a

wonderful brightness, enter the prison. He took us to all parts to make us go

out, but there was no outlet; then he said to me, ‘You have still some concern

at your being retained here, but be not discouraged, I am with you: carry these

tidings to your companions, and let them know that they shall have a more

glorious crown.’ I asked him where heaven was; the infant replied, ‘Out of the

world.’” Show it me, says Victor. The infant then answered, “Where then would

be your faith?” Victor said, “I cannot retain what you command me: tell me a

sign that I may give them.” He answered, “Give them the sign of Jacob, that is,

his mystical ladder, reaching to the heavens.” Soon after this vision, Victor

was put to death. This vision filled us with joy.

God gave us, the

night following, another assurance of his mercy by a vision to our sister

Quartillosia, a fellow-prisoner, whose husband and son had suffered death for

Christ three days before, and who followed them by martyrdom a few days after.

“I saw,” says she, “my son who suffered; he was in the prison sitting on a

vessel of water, and said to me: ‘God has seen your sufferings.’ Then entered a

youug man of a wonderful stature, and he said: ‘Be of good courage, God hath

remembered you.’” The martyrs had received no nourishment the preceding day,

nor had they any on the day that followed this vision; but at length Lucian,

then priest, and afterwards bishop of Carthage, surmounting all obstacles, got

food to be carried to them in abundance by the subdeacon, Herennian, and by

Januarius, a catechumen. The acts say they brought the never failing food, 2 which Tillemont understands of the blessed eucharist, and the following

words still more clearly determine it in favour of this sense. They go on: We

have all one and the same spirit, which unites and cements us together in

prayer, in mutual conversation, and in all our actions. These are those amiable

bands which put the devil to flight, are most agreeable to God, and obtain of

him, by joint prayer, whatever they ask. These are the ties which link hearts

together, and which make men the children of God. To be heirs of his kingdom we

must be his children, and to be his children we must love one another. It is

impossible for us to attain to the inheritance of his heavenly glory, unless we

keep that union and peace with all our brethren which our heavenly Father has

established amongst us. Nevertheless, this union suffered some prejudice in our

troop, but the breach was soon repaired. It happened that Montanus had some

words with Julian, about a person who was not of our communion, and who was got

among us (probably admitted by Julian). Montanus on this account rebuked

Julian, and they, for some time afterwards, behaved towards each other with

coldness, which was, as it were, a seed of discord. Heaven had pity on them

both, and, to reunite them, admonished Montanus by a dream, which he related to

us as follows: “It appeared to me that the centurions were come to us, and that

they conducted us through a long path into a spacious field, where we were met

by Cyprian and Lucius. After this we came into a very luminous place, where our

garments became white, and our flesh became whiter than our garments, and so

wonderfully transparent, that there was nothing in our hearts but what was

clearly exposed to view: but in looking into myself, I could discover some

filth in my own bosom; and, meeting Lucian, I told him what I had seen, adding,

that the filth I had observed within my breast denoted my coldness towards

Julian. Wherefore, brethren, let us love, cherish, and promote, with all our

might, peace and concord. Let us be here unanimous in imitation of what we

shall be hereafter. As we hope to share in the rewards promised to the just,

and to avoid the punishments wherewith the wicked are threatened: as, in fine,

we desire to be and reign with Christ, let us do those things which will lead

us to him and his heavenly kingdom.” Hitherto the martyrs wrote in prison what

happened to them there: the rest was written by those persons who were present,

to whom Flavian, one of the martyrs, had recommended it.

After suffering

extreme hunger and thirst, with other hardships, during an imprisonment of many

months, the confessors were brought before the president, and made a glorious

confession. The edict of Valerian condemned only bishops, priests, and deacons

to death. The false friends of Flavian maintained before the judge that he was

no deacon, and, consequently was not comprehended within the emperor’s decree;

upon which, though he declared himself to be one, he was not then condemned;

but the rest were adjudged to die. They walked cheerfully to the place of

execution, and each of them gave exhortations to the people. Lucius, who was

naturally mild and modest, was a little dejected on account of his distemper,

and the inconveniences of the prison; he therefore went before the rest,

accompanied but by a few persons, lest he should be oppressed by the crowd, and

so not have the honour to spill his blood. Some cried out to him, “Remember

us.” “Do you also,” says he, “remember me.” Julian and Victorius exhorted a long

while the brethren to peace, and recommended to their care the whole body of

the clergy, those especially who had undergone the hardships of imprisonment.

Montanus, who was endued with great strength, both of body and mind, cried out,

“He that sacrificeth to any God but the true one, shall be utterly destroyed.”

This he often repeated. He also checked the pride and wicked obstinacy of the

heretics, telling them that they might discern the true church by the multitude

of its martyrs. Like a true disciple of Saint Cyprian, and a zealous lover of

discipline, he exhorted those that had fallen not to be over hasty, but fully

to accomplish their penance. He exhorted the virgins to preserve their purity,

and to honour the bishops, and all the bishops to abide in concord. When the

executioner was ready to give the stroke, he prayed aloud to God that Flavian,

who had been reprieved at the people’s request, might follow them on the third

day. And, to express his assurance that his prayer was heard, he rent in pieces

the handkerchief with which his eyes were to be covered, and ordered one half

of it to be reserved for Flavian, and desired that a place might be kept for

him where he was to be interred, that they might not be separated even in the

grave. Flavian, seeing his crown delayed, made it the object of his ardent

desires and prayers. And as his mother stuck close by his side with the

constancy of the mother of the holy Maccabees, and with longing desires to see

him glorify God by his sacrifice, he said to her: “You know, mother, how much I

have longed to enjoy the happiness of dying by martyrdom.” In one of the two

nights which he survived, he was favoured with a vision, in which one said to

him: “Why do you grieve? You have been twice a confessor, and you shall suffer

martyrdom by the sword.” On the third day he was ordered to be brought before

the governor. Here it appeared how much he was beloved by the people, who

endeavoured by all means to save his life. They cried out to the judge that he

was no deacon; but he affirmed that he was. A centurion presented a billet

which set forth that he was not. The judge accused him of lying to procure his

own death. He answered: “Is that probable? and not rather that they are guilty

of an untruth who say the contrary?” The people demanded that he might be

tortured in hopes he would recall his confession on the rack; but the judge

condemned him to be beheaded. The sentence filled him with joy, and he was

conducted to the place of execution, accompanied by a great multitude, and by

many priests. A shower dispersed the infidels, and the martyr was led into a

house where he had an opportunity of taking his last leave of the faithful

without one profane person being present. He told them that in a vision he had

asked Cyprian whether the stroke of death is painful, and that the martyr

answered; “The body feels no pain when the soul gives herself entirely to God.”

At the place of execution he prayed for the peace of the church and the union

of the brethren; and seemed to foretell Lucian that he should be bishop of

Carthage, as he was soon after. Having done speaking, he bound his eyes with

that half of the handkerchief which Montanus had ordered to be kept for him,

and, kneeling in prayer, received the last stroke. These saints are joined

together on this day in the present Roman and in ancient Martyrologies.

Note 1. Apud regionantes. [back]

Note 2. Alimentum indeficiens. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume II: February. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

Santi Lucio, Montano e compagni Martiri

23 maggio

m. 259

Martirologio Romano: A Cartagine, nell’odierna

Tunisia, santi Lucio, Montano, Giuliano, Vittorìco, Vittore e Donaziano,

martiri, che, per la religione e la fede che avevano appreso dall’insegnamento

di san Cipriano, affrontarono il martirio sotto l’imperatore Valeriano.

San MONTANO, Martire

Discepolo di Cipriano, subì il martirio a Cartagine nel 259 sotto l’impero di

Valentiniano. Dopo che a Cartagine aveva avuto luogo una sedizione popolare,

l’autorità civile mise in atto un’azione repressiva nei confronti dei

cristiani. Montano venne arrestato per ordine del governatore, e insieme a

Lucio, Flaviano, Giuliano, Vittorico, Primolo, Iteno e Donaziano, fu portato in

carcere e lasciato là alcuni mesi a soffrire la fame e la sete. Quindi venne

condotto davanti al giudice per essere interrogato, e continuò coraggiosamente

a professare la sua fede in Cristo, fino a quando subì l’estremo supplizio.

Mentre, si avviava a incontrare il suo carnefice sotto gli occhi del popolo

incuriosito, mostrava un aspetto gioioso e invitava tutti alla carità e

all’unità.

Montano con i suoi compagni è protagonista di una passione, ovvero la “Passio

SS. Montani et Luci” (cfr. BHL 6009) ed è menzionato in vari calendari antichi.

La “Passio SS. Montani et Luci”, il “Calendarium Carthaginensis” e il “Martyrologium

hieronymianum” pongono al 23 maggio il supplizio di Montano e Lucio e al 25

maggio il supplizio di Flaviano. Viceversa il “Martyrologium Romanum”,

probabilmente sbagliando, assegna la festa di Montano e di tutti i suoi

compagni al 24 febbraio.

Il culto di Montano nella zona di Tebessa è attestato da un’iscrizione, non

anteriore al VI secolo, appartenente all’altare della basilica di

Henchir-el-Beguer.

Autore: Paola Marone

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/54410

Nome: Santi Lucio, Montano e compagni

Titolo: Martiri

Ricorrenza: 23 maggio

Tipologia: Commemorazione

Questi martiri cartaginesi Subirono tutti il martirio durante la persecuzione

di Valeriano, nel corso della quale fu ucciso anche S. Cipriano (16 set.). Gli

Atti a loro contemporanei sono generalmente accettati come veri e degni di

fede, fornendo un legame diretto con coloro che nell'Africa del secolo patirono

per Cristo. Il governatore Solone era stato il bersaglio di un'insurrezione a

Cartagine, e invece di indagare per scoprire il vero colpevole, fece arrestare

otto cristiani, molti dei quali erano chierici di Cipriano, e tutti suoi

discepoli.

Subito dopo il loro arresto i servi del governatore dissero loro che sarebbero

stati arsi vivi: essi però pregarono con fervore di essere liberati da quella

punizione.

Vennero poi rinchiusi «in una prigione molto buia e scomoda [...] ma non

eravamo spaventati dalla sporcizia del posto, perché la nostra fede e gioia

nello Spirito Santo ci riconciliarono con le soffe-renze, anche se erano tali

da non poter essere facilmente descritte». Reno ebbe anche la visione di

parecchi prigionieri che uscivano fuori, preceduti da una lampada accesa: erano

i futuri martiri che seguivano Cristo, vera lucerna per i loro passi.

Il giorno seguente il governatore mandò a prenderli per interrogarli: «Fu un

trionfo per noi essere resi come uno spettacolo attraverso il luogo del mercato

e lungo le strade con le nostre catene che risuonavano».

Il governatore li interrogò; le loro risposte furono miti e ferme. Furono così

rispediti in prigione, dove rimasero senza cibo c bevanda per molti giorni.

Si registrarono altre visioni. Il prete Luciano riuscì infine a ottenete da un

suddiacono e un catecumeno portassero loro del cibo. Questo «cibo che non viene

mai meno» fu probabilmente l'eucaestia.

Ugualmente straordinaria era l'esigenza di condividere lo spirito della carità:

«Noi abbiamo tutti un solo e unico spirito che ci unisce e ci lega nella

preghiera, nei rapporti vicendevoli e in tutte le nostre azioni. Sono questi i

vincoli d'amore che spingono il diavolo alla fuga e sono molto graditi a Dio

[...] questi sono i legami che uniscono insieme i cuori e rendono gli uomini

figli di Dio [...]

È impossibile per noi ottenere l'eredità della gloria celeste, se non

conserviamo con i nostri fratelli quell'unione e quella pace che il Padre

celeste ha costituito tra noi».

Queste sono le parole dei martiri; il resto della loro vicenda fu descritto da

alcuni testimoni, come Flaviano, prima di morire, raccomandò loro.

Dopo essere stati imprigionati per alcuni mesi in durissime condizioni, patendo

oltre misura la fame e la sete, fecero una gloriosa professione di fede.

Ciascuno di essi camminò fino al luogo dell'esecuzione ed esortò il popolo.

Un certo Montano denunciò l'orgoglio e l'ostinazione degli eretici, dicendo

loro che avrebbero potuto riconoscere la vera Chiesa dalla moltitudine dei suoi

martiri. Esortò coloro che avevano ritrattato a completare la loro penitenza e

incoraggiò l'insieme dei vergini a conservare la loro purezza e a onorare i

vescovi.

Poi pregò ad alta voce che Flaviano, di cui per richiesta del popolo era stata

sospesa l'esecuzione, potesse seguirli il terzo giorno. Egli divise in due

parti la benda che gli doveva coprire gli occhi, lasciandone una metà per

Flaviano e chiedendo di poter dividere con lui la stessa tomba.

Fu quindi giustiziato con la spada. Flaviano lo seguì pochi giorni più tardi,

dopo aver consolato la madre ed essere stato sottoposto alla tortura. Disse ai

cristiani che lo seguivano che S. Cipriano, gli aveva assicurato in visione che

«il corpo non avverte il dolore, quando l'anima si offre interamente a Dio».

Sul luogo dell'esecuzione pregò per la pace e l'unità della Chiesa e dei

fratelli. Bendandosi gli occhi con la metà della benda di Montano e

inginocchiandosi in preghiera, ricevette l'ultimo colpo. In passato questi

martiri erano venerati il 24 febbraio.

MARTIROLOGIO ROMANO. A Cartagine, nell’odierna Tunisia, santi Lucio,

Montano, Giuliano, Vittoríco, Vittore e Donaziano, martiri, che, per la

religione e la fede che avevano appreso dall’insegnamento di san Cipriano,

affrontarono il martirio sotto l’imperatore Valeriano.

SOURCE : https://www.santodelgiorno.it/santi-lucio-montano-e-compagni/

LUCIO, MONTANO E I LORO COMPAGNI

Una cieca retata di polizia provoca l'arresto di

parecchi cristiani della comunità cartaginese. Due di loro muoiono in carcere.

Altri cinque saranno giustiziati, nel maggio del 259, dopo otto mesi di

interrogatori, di privazioni e di sofferenze. A guisa di memoriale, i

prigionieri redigono una lettera che riferisce le condizioni della loro

detenzione e proclama la loro speranza.

Completata dopo il loro martirio da un testimone

oculare, questa lettera è oggi uno dei più commoventi documenti antichi

sull'universo carcerario. Nell'oscurità e nell'afa di una cella, spossati dalla

fame e dalla sete, angosciati dall'attesa interminabile della morte, i

detenuti, dei quali si ignora la posizione esatta all'interno della Chiesa, si

rifugiano nella preghiera e nei sogni. Questi, abbaglianti di luce, non hanno bisogno,

per essere interpretati, dei manuali di oniromanzia pagana: essi parlano di

bevande rinfrescanti e di sbarre che cadono, di un fanciullo-guida nella notte

e di un aldilà risplendente in cui si è accolti dal vescovo Cipriano

di Cartagine, da poco decapitato.

Dietro a ogni avvenimento della loro prigionia, questi

comuni cristiani scoprono la presenza del Dio di misericordia al quale il

salmista fa dire: «Invocami nel giorno dell'angoscia, io ti libererò e tu mi

renderai gloria ... Scritta in una lingua relativamente sobria, quest'opera si

colloca nella tradizione inaugurata dalla Passione delle sante

Perpetua e Felicita. Lucio e i suoi compagni hanno voluto, espressamente,

insegnare alle generazioni future che la repressione più violenta non ha il

potere di spezzare coloro che camminano sulle orme di Cristo. La nostra sola

fonte di informazione su Lucio e i suoi compagni è il racconto in latino della

loro prigionia e del loro martirio, considerato fin dal XVI secolo come uno dei

gioielli della letteratura cristiana antica.

In seguito a una sommossa che era degenerata in un

tentativo d'assassinio a danno del proconsole d'Africa, otto cristiani di

Cartagine sono arrestati dalla polizia. La condanna a morte del vescovo

Cipriano, eseguita alcuni giorni prima, il 14 settembre del 258, aveva già

provocato veementi proteste e anche dei tafferugli. In una provincia

regolarmente agitata da forze centrifughe (essa tenterà anche la secessione

intorno al 265), la situazione è tesa per il potere.

Una lettera dal carcere

La prima parte della Passione dei martiri è una

lettera collettiva, inviata dai prigionieri ai loro fratelli cristiani rimasti

in libertà. Parecchi documenti di questo tipo si sono conservati tanto in greco

quanto in latino, in particolare nella corrispondenza di san Cipriano:

espressione letteraria di uno spirito comunitario che pare non avere

l'equivalente nel mondo pagano. Dalla seconda parte della Passione apprendiamo

il nome del redattore principale della lettera: si tratta di Flaviano, che,

dopo aver citato il proprio nome al terzo posto nell'enumerazione iniziale, ha

evitato in seguito di mettersi in scena.

Ma l'ispirazione del testo, che manca talora di

coerenza, rimane autenticamente collettiva. Il racconto in prima persona

plurale si interrompe solamente quando l'uno o l'altro dei prigionieri narra ai

compagni di carcere i suoi sogni notturni. Oltre che ai fratelli di Cartagine,

il documento si rivolge espressamente alle generazioni future, a «testimonianza

fedele della magnificenza di Dio» e a «memoria delle sofferenze sopportate con

l'aiuto del Signore». Gli otto cristiani sono in un primo momento sorvegliati a

vista. Costretti a udire le chiacchiere dei guardiani, che predicono loro il

rogo, essi vivono per qualche ora nel terrore di un supplizio che, agli occhi

di persone semplici, pareva impedire ogni possibilità di resurrezione futura

della carne. Con sollievo perciò essi si vedono incarcerati nella cittadella di

Cartagine, nonostante l'oscurità della cella.

La relazione del martirio

Ciò che segue non è più che una lunga attesa, nei

tormenti della sete, della fame e della malattia: attesa punteggiata solamente

dalle convocazioni giudiziarie e dalle visite dall'esterno. Lucio e i suoi

compagni hanno trovato in prigione altri fratelli, tra i quali una donna,

Quartillosia, il cui figlio e il cui marito avevano già subito il martirio. In

questo piccolo gruppo che cerca di vivere nella carità, la promiscuità non

sembra essere sentita come una sofferenza. I detenuti si comunicano i loro

sogni, nei quali cercano instancabilmente di leggere il loro avvenire e di

trovare dei motivi di speranza. Si intuisce infatti che l'indebolimento

progressivo dei corpi fa temere la capitolazione delle volontà. Il messaggio

finale della lettera è un'esortazione «alla concordia, alla pace e all'unità»,

il che fa pensare che la Chiesa di Cartagine, come già nove anni prima sotto il

regno di Decio, si fosse divisa dinanzi alla persecuzione. La parte che segue è

meglio costruita, ma più convenzionale. Degli otto cristiani arrestati verso la

fine di settembre del 258, due sono morti in prigione: Primolo e Donaziano.

La sorte di un terzo, Reno, non è precisata, ma si può

supporre con una certa verosimiglianza che sia stato rilasciato. Flaviano ha

affidato a un amico l'incarico di riferire il processo e l'esecuzione dei

cinque ultimi membri del gruppo. L'udienza, però, non si svolge esattamente

come era stato previsto. Tutti confessano la loro fede, ma l'avvocato di

Flaviano, al fine di permettere a questo di sfuggire alle disposizioni della

legge, nega che il suo cliente sia diacono. Un tale argomento rende necessario

un supplemento d'inchiesta, di modo che il caso di Flaviano si trova disgiunto

da quello dei suoi quattro coimputati. Egli è ricondotto in carcere mentre i

suoi compagni, condannati a morte, vanno gioiosi al supplizio. Lucio, timido

per natura e indebolito dalla prigionia, teme la ressa, e si apparta con poche

persone alle quali manifesta sino alla fine la sua umiltà. Giuliano e Vittorico

raccomandano ai fratelli i chierici che hanno fatto loro visita in carcere.

Montano, le cui forze sono rimaste intatte e che è sempre stato sicuro nel

parlare, arringa a lungo la folla degli amici e dei curiosi.

Le sue parole, che riflettono l'insegnamento di

Cipriano, si rivolgono, con un'autorità profetica, agli scismatici e alle

diverse componenti della comunità cristiana: come la lettera collettiva,

anch'esse si chiudono con un appello ardente alla pace della carità. Alcuni

istanti prima di essere decapitato con la spada, nel momento in cui gli si

coprono gli occhi, Montano fa tenere da parte metà della benda per Flaviano e

chiede a Dio per l'amico la grazia del martirio entro tre giorni. La fine della

Passione dimostra che una giusta preghiera è esaudita dal Signore. La dilazione

imposta a Flaviano da amici maldestri è per lui un'occasione di esercitare la

sua pazienza. Sua madre, pari per fervore a quella dei Maccabei, vera figlia di

Abramo, si affligge nel veder rinviare il martirio del suo unico figlio: egli

la consola dimostrandole la sua costanza. Ai condiscepoli pagani che lo

esortano a sacrificare per pura formalità e a scegliere la vita piuttosto che

la morte, egli risponde che la morte, agli occhi di un cristiano, non è che

apparenza. Il terzo giorno, Flaviano compare di nuovo dinanzi al proconsole.

I suoi amici hanno fabbricato un falso per salvarlo,

ma egli riafferma di essere diacono e, nonostante l'imbarazzo evidente del

magistrato e la rumorosa simpatia del pubblico, ottiene di essere condannato.

La sua morte, in mezzo a un grande concorso di popolo, assomiglia più a un

trionfo che a un'esecuzione capitale. Un violento acquazzone consente

provvidenzialmente al piccolo gruppo dei fratelli di appartarsi per un ultimo

bacio di pace. Flaviano ricorda ai membri della comunità il duplice

comandamento dell'unità e dell'amore e raccomanda un candidato alla successione

di Cipriano. Muore pregando, con gli occhi coperti dalla benda che gli aveva

lasciato Montano.

Sette racconti di sogni

I sogni assicurano l'unità dell'opera e conferiscono

ad essa, per un lettore d'oggi, il suo tono così particolare. Quattro sono riferiti

e subito interpretati nella lettera collettiva. Altri tre, di cui Flaviano è

stato il beneficiario e sui quali egli aveva taciuto per discrezione, sono

narrati dal cronista degli ultimi giorni dei martiri. Analoghi a quelli che

sono esposti in altre Passioni africane (in particolare quella di Perpetua e

Felicita), essi sono stati ampiamente commentati dagli psicanalisti e dagli

storici moderni, che sono in generale d'accordo nel riconoscere il loro

carattere non letterario. I racconti più lunghi sono vicini alla lingua parlata

e si distinguono nettamente, sul piano stilistico, dalle parti narrative che

sono attribuibili a Flaviano o al suo continuatore anonimo. Avrebbe però torto

chi vedesse in questa diversità un motivo per isolare i sogni dal loro contesto

interpretativo e per considerarli come documenti greggi. Un testo agiografico è

sempre una forma di preparazione, e i redattori scelgono ciò che deve entrare a

fame parte in riferimento ai loro scopi apologetici o parenetici.

Quello che oggi è visto come un fenomeno psichico,

legato al subcosciente dell'individuo, non era altro, per questi cristiani del

III secolo, che un messaggio implicito e premonitore della compassione divina.

Nonostante le condizioni penose in cui vivevano i prigionieri, non è fatta

parola di alcun incubo. Colui che sogna prova semplicemente una sensazione

oscura di disagio, un'inquietudine diffusa che corrisponderebbe, in uno stato

di veglia, a un momento di depressione spirituale.

La parte successiva del sogno reca una risposta positiva

e luminosa, tanto più abbagliante quanto più si avvicina il momento cruciale

della grande prova. I quattro sogni che sono inseriti nella lettera iniziale

formano una specie di rivelazione progressiva del disegno di Dio riguardo ai

suoi servitori sofferenti. In conformità con la profezia di Isaia (IX, 1), Reno

non vede dapprima che delle lucerne che precedono i prigionieri, i quali

camminano ancora senza meta nelle tenebre. Il prete Vittorico, che era già in

carcere quando vi sono giunti Lucio e i suoi compagni, fa un passo in più nella

contemplazione del mistero: le lucerne di Reno sono divenute il volto

risplendente di un fanciullo-guida, ma nessuna via d'uscita si apre dinanzi ai

prigionieri; la vista del paradiso è negata a Vittorico, che riceve l'incarico,

in quanto prete, di incoraggiare i fratelli ricordando loro le parole che

concludono la visione di Giacobbe: «In verità, il Signore è in questo luogo e

io non lo sapevo ! ... Quanto è terribile questo luogo ! Esso è proprio la casa

di Dio e la porta del cielo» (Genesi, XXVIII, 16-17).

La tappa successiva è superata da Quartillosia, che è

più degli altri protesa verso il martirio, in quanto anela a ricongiungersi con

il figlio e il marito, già incoronati nella prova. « Vidi - ella dice - venire

qui nel carcere mio figlio, che ha sofferto la sua passione; sedendo sulla

vasca dell'acqua, egli disse: "Dio ha visto la vostra tribolazione e la

vostra sofferenza". E dopo di lui entrò un giovane di statura

straordinaria, che portava, una per mano, due coppe piene di latte, e disse:

"Fatevi coraggio, Dio si è ricordato di voi ". E da quelle coppe che

portava diede a tutti da bere, e le coppe non si svuotavano. E d'un tratto fu

tolta la pietra che divideva in due la finestra; ed ecco anche le sbarre della

finestra stessa, tolte di mezzo, lasciarono entrare liberamente la vista del

cielo. E il giovane posò a terra le coppe che portava, una a destra e l'altra a

sinistra, e disse: "Ecco, siete sazi e vi rimane latte in abbondanza, e vi

sarà data ancora una terza coppa". E se ne andò».

I corpi sono ancora prigionieri, ma la «porta del

cielo» è ormai aperta. Il fanciullo si è trasformato in giovane; il confronto

non deriva più dalla meditazione sulle Scritture, ma dal cibo eucaristico

(portato, fin dall'indomani, da un suddiacono e da un catecumeno). La terza

coppa annunciata sembra essere quella del martirio. A Montano infine è

riservata la rivelazione ultima. I centurioni che, nella realtà, avevano

assurdamente girato in cerchio nel foro senza sapere dove dovessero condurre

gli imputati, guidano questa volta i loro prigionieri in una pianura lontana,

immensa e scintillante di candore. La presenza, in questo luogo, di Cipriano

rivela che si tratta del paradiso dei giusti, celato poco prima a Vittorico. La

luce che vi regna era prefigurata, nelle visioni precedenti, dalle lucerne, dal

volto radioso del fanciullo e dalla sinistra aperta sul cielo.

Essa richiede non solo il candore di una veste

nuziale, ma anche la trasparenza assoluta del cuore. La lunga attesa dei detenuti

si spiega con la necessità di purificarsi da ogni sozzura. Nel Regno possono

entrare solamente coloro che sono divenuti essi stessi luce nella notte per gli

altri. Nel racconto redatto dal continuatore anonimo, i tre sogni di Flaviano

presentano una progressione analoga. Dapprima preoccupato per il timore della

sofferenza, poi angosciato dall'idea di essere separato dai compagni, il

martire perviene infine, nel suo ultimo sogno, alla pace interiore. Questa

riconciliazione con se stesso è simboleggiata dall'elogio pubblico che fa di

lui sua madre e dal fatto che un vescovo in persona, già rivestito di luce, è

inviato ad annunciargli l'imminenza della passione. Poiché ha conquistato la

pace, Flaviano è divenuto degno del sacrificio. La stretta corrispondenza tra

la realtà e il sogno procede da una riflessione, individuale e collettiva, sul

valore religioso del martirio.

I santi e il loro ambiente

Questi confessori cartaginesi, che nella tribolazione

hanno voluto divulgare i loro sogni, le loro angosce e le loro speranze,

rimangono sotto molti aspetti degli sconosciuti. L'introduzione della loro

lettera ci fa sapere che Donaziano e Primolo erano catecumeni. Vittorico, che

riceve l'incarico di commentare per i compagni di prigionia la visione di

Gia-obbe, è prete. Una circostanza del processo consente di attribuire a

Flaviano il titolo di diacono. Di tutti gli altri, si ignorano completamente la

condizione sociale e la posizione precisa all'interno della comunità cristiana.

Gli storici moderni hanno supposto che i quattro condannati del 23 maggio 259 -

Lucio, Montano, Giuliano e Vittorico - facessero parte anch'essi del clero,

come se la qualità di laico riconosciuta a Flaviano fosse tale da permettere a

questo di sfuggire alla pena capitale.

Si dimentica in realtà che il secondo editto di

Valeriano colpiva anche notabili e funzionari e che inoltre l'arresto degli

imputati era stato conseguente a una sommossa. Famiglie intere, come quella di

Quartillosia, furono eliminate nel corso della persecuzione, che evidentemente

non si limitò ai vescovi, preti e diaconi. È dunque imprudente voler a tutti i

costi precisare ciò che gli autori della nostra unica fonte hanno passato sotto

silenzio. Risulta chiaro tuttavia, dai discorsi dei martiri, che i tre

protagonisti - Lucio, Montano e Flaviano - hanno beneficiato direttamente degli

insegnamenti di Cipriano e conoscevano dall'interno i dissidi esistenti nella

Chiesa cartaginese.

Ciascuno di loro ha una sua personalità ben precisa:

Lucio è fragile e modesto; Montano è invece noto per la sua eloquenza e non

risparmia i consigli; Flaviano è ancora vicino al mondo delle scuole, e sono i

suoi antichi compagni di studi che tentano di salvarlo contro la sua volontà;

del resto, l'amico a cui egli ha affidato l'incarico di continuare la sua opera

è anche lui un intellettuale, esperto nelle finezze della retorica e della

prosa metrica. Il racconto iniziale della prigionia e le ultime parole dei

condannati ci fanno conoscere certi aspetti della società africana del III

secolo. La comunità cristiana è profondamente divisa, e non è un caso che il

tema fondamentale della Passione sia quello della pace che deve regnare tra i

fratelli. Lo scisma causato dagli strascichi della persecuzione di Decio non è

ancora stato riassorbito. Parecchi cristiani che hanno abiurato sotto le

minacce cercano indebitamente di sfuggire alle conseguenze disciplinari della

loro debolezza. Per una sorta di contraccolpo, le numerose scomuniche provocano

dei contrasti nelle file stesse dei fedeli. Ma queste ombre non devono far

dimenticare il fervore dei prigionieri, la coraggiosa solidarietà di una parte

del clero con i detenuti, la carità sollecita dei fratelli verso i condannati a

morte.

L'impronta lasciata da Cipriano è profonda, e il

vescovo martire rimane i riferimento ultimo dei cristiani nella tempesta. La

società pagana, dal canto suo, non compare sotto una luce polemica. I

magistrati persecutori non sono chiamati per nome, poiché sono solamente gli

strumenti di un padrone esigente che è il diavolo: «Perché dovrei adirarmi,

dice Flaviano, contro un uomo che ripete soltanto ciò che gli è ordinato di

dire ?».

I rappresentanti del potere sono manifestamente messi

a disagio da una repressione impopolare e temono le udienze pubbliche. Il nuovo

proconsole non ha le medesime ragioni del suo predecessore di lasciarsi

trascinare dalla collera: si accontenterebbe di un falso per evitare a Flaviano

una sentenza di morte, se l'accusato stesso si mostrasse maggiormente disposto

a collaborare, e quando la folla si esaspera non acconsente a servirsi della

tortura. I guardiani del carcere sono naturalmente più rozzi e non hanno alcun

motivo di riservare al cristiano un trattamento privilegiato: sono capaci

tuttavia di chiudere gli occhi su certe visite dall'esterno, se lo si chiede

loro con le parole giuste. Il racconto sugli ultimi giorni dei martiri mostra

chiaramente che i cristiani godevano di grande simpatia presso i pagani. Per

amicizia nei confronti di Flaviano si tenta di ingannare in suo favore la

giustizia ufficiale.

I suoi compagni di studi accettano senza difficoltà la

credenza del loro amico in un Dio unico e creatore, ma non riescono a

comprendere il suo desiderio di morte carnale, che essi interpretano come una

follia suicida. Al momento dell'ultima udienza in tribunale, che vedrà la

condanna di Flaviano, il pubblico non è veramente ostile: se chiede che si

ricorra alla tortura, è per una sorta di pietà distorta, per spezzare cioè

l'ostinazione di un accusato sordo ad argomenti meno convincenti. La luce sotto

la quale appare la società cartaginese non ha nulla, è chiaro, di

convenzionale.

Autenticità e sopravvivenza del documento

Somiglianze incontestabili - a un duplice livello,

stilistico e aneddotico - tra la Passione delle sante Perpetua e Felicita e