Saint Guthlac holding the scourge (whip) given to him by Saint Bartholomew and a demon at his feet. The statue from the second tier of the Croyland Abbey's west front of the ruined nave; dates from the XVth century.

Saint Guthlac

(+ 714)

Il vécut d'abord comme un

véritable bandit en Angleterre. Mais il laissait toujours un tiers de

leurs biens à ceux qu'il dépouillait. A 24 ans, il voulut retrouver une vie

plus innocente et se fit ermite dans un îlot de l'estuaire du Wash. Les oiseaux

venaient l'entourer et chanter pour lui. Il s'y livra à de grandes austérités

et, sur son tombeau, s'édifia l'abbaye de Crowland.

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/6532/Saint-Guthlac.html

The quatrefoil above the West Door of the Croyland Abbey shows in relief scenes from the life of Saint Guthlac. The sculpture dates from the middle years of the XIIIth century.

Saint Guthlac de Croyland

Ermite en Est-Anglie

Fête le 11 avril

OSB

en Mercie v. 674 – †

Croyland, Lincolnshire, 11 avril 714

Autres mentions : 12

avril – 30 août – 26 août

Autre graphie :

Guthlac of Crowland

Tout ce que nous savons

de Guthlac provient d’une « Vie » de ce saint, rédigée au VIIIe

siècle, et assurément digne de crédit. Né vers 673, il était parent de la

maison royale de Mercie. Dans sa jeunesse, il prit part aux guerres de

succession, commandant une bande armée, attaquant les villes, massacrant les

ennemis, et se livrant en toute occasion au pillage. Il se convertit aux

environs de sa vingt-quatrième année et entra au monastère double de Repton,

que dirigeait alors l’abbesse Elfrida. Sa vocation le poussait à la vie

érémitique ; ayant reçu permission de l’abbesse, il s’établit, avec deux

compagnons, dans une île des Fens, marécages de l’est de la Grande-Bretagne,

autour de l’estuaire du Wash, lieu futur de l’abbaye de Crowland ou Croyland,

dans les environs de Peterborough. Peu à peu de nombreux disciples venaient

occuper des cellules voisines de la sienne. Bien que sa sœur, sainte Pègue,

vécût en anachorète tout près de lui, à Peakirk (Pega’s Kirk, « église de Pègue »),

il refusa toujours de la voir. Il devait pourtant, sentant la mort approcher,

l’inviter à son enterrement. L’abbesse de Repton lui envoya son cercueil. Il

mourut le 11 avril 714. L’abbaye de Crowland, fut construite en 716 par

Ethelbald, roi de Mercie, sur l’emplacement de la cellule de saint Guthlac.

SOURCE : http://www.martyretsaint.com/guthlac-de-croyland/

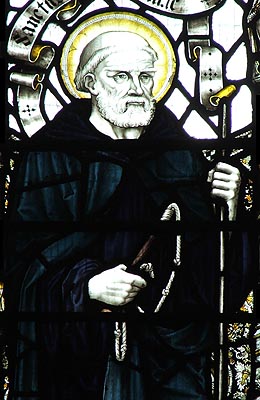

Stained

glass panel depicting Guthlac of Crowland, in Crowland

Abbey

Saint Guthlac de

Croyland, ermite

Né en Mercie, vers 673; mort à Crowland, Lincolnshire, Angleterre en 714;

originellement fêté le 12 avril; fête de sa translation le 30 août, et on le

commémore aussi le 26 août.

Comme jeune homme de sang royal, du clan des Guthlacingas, Guthlac avait été

soldat 9 ans durant, combattant pour Ethelred, roi de Mercie. A l'âge de 24

ans, il renonça tant à la violence qu'à la vie du monde et devint moine dans la

double-abbaye de Repton, qui était dirigée par une abbesse appelée Elfrida.

Même en ces jeunes années, sa discipline était extraordinaire. Certains des

moines ne l'aimaient pas parce qu'il refusait tout vin et toute boisson

enivrante. Mais il passait outre des critiques et finit par gagner le respect

de ses frères. Après 2 ans dans le monastère, cela lui sembla un lieu trop

agréable. Lors de la fête de saint Barthélémy vers 701, il trouva un endroit

reclus, humide, désagréable, sur la rivière Welland, dans les Fens, qu'on ne

pouvait atteindre qu'en bateau, et il y vécut en ermite le restant de sa vie,

cherchant à imiter les rigueurs des anciens pères du désert.

Ses tentations rivalisèrent les leurs. Des sauvages sortirent de la forêt et le

battirent. Même les corbeaux lui volèrent le peu qu'il avait. Mais Guthlac

était patient, même avec les créatures sauvages. Petit à petit, les animaux et

les oiseaux commencèrent à lui faire confiance, comme à un ami. Un saint homme

appelé Wilfrid visita Guthlac un jour, et fut étonné de voir 2 hirondelles se

posant sur ses épaules, puis lui sautillant dessus. Guthlac lui dit :

"N'as-tu pas appris, frère, que celui qui aura mené une vie conforme à la

volonté de Dieu, les bêtes sauvages et les oiseaux lui deviendront intimes,

comme pour ceux qui quittent le monde, les Anges se rapprochent?".

Apparemment, Guthlac eut aussi une vision de saint Barthélémy, son patron. Il ne

restera pas seul dans son refuge : il aura plusieurs disciples, Saints Cissa,

Bettelin, Egbert, et Tatwin, qui auront une cellulle proche de la sienne.

L'évêque Hedda de Dorchester l'ordonnera à la prêtrise durant une visite. Le

prince exilé Ethelbald venant souvent le voir pour un conseil, apprendra de

Guthlac qu'il porterait un jour la couronne des Merciens.

A l'article de la mort, Guthlac fit quérir sa soeur, sainte Pega, qui était

ermitesse dans le même voisinage (Peakirk ou église de Pega). L'abbesse Edburga

de Repton lui envoya un linceul et un cercueil de plomb. Un an après sa mort,

le corps de Guthlac fut exhumé et trouvé incorrompu. Bien vite son tombeau,

dans lequel sa soeur avait aussi placé son Psautier et son fouet, devint

populaire. Lorsqu'ensemble, le roi Wiglaf de Mercie (827-840) et l'archevêque

Ceolnoth de Canterbury (qui avait été guérit par Guthlac de la fière paludéenne

en 851) devinrent ses fidèles, le culte de Guthlac grandit et se répandit. Un

monastère fut fondé sur l'emplacement de l'ermitage de saint Guthlac, qui se

développa en la grande abbaye de Crowland, dans laquelle ses reliques furent

transférées en 1136. Il y eut une nouvelle translation en 1196.

On peut aller de nos jours en pèlerinage sur le site, qui est très intéressant,

mais il ne reste hélas rien de l'époque du saint, car tout fut détruit par les

envahisseurs païens qui ravagèrent la région à l'époque. Ceux qui ont fréquenté

Cambridge se souviendront que leur université a été fondée sous l'inspiration

de l'abbé de Crowland, et comme le rappelle Sabine Baring-Gould, cela fait donc

de saint Guthlac le père spirituel de cette université.

La Vita de Guthlac fut rédigée en latin par Félix, un quasi contemporain.

D'autres furent composées en Vieil Anglais, en vers comme en prose. Avec saint

Cuthbert, Guthlac a été un des saints ermites les plus populaires dans

l'Angleterre d'avant la Conquête. (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Farmer,

Gill, Husenbeth).

Dans l'art, Saint Guthlac est dépeint avec un fouet en main et un serpnet à ses

pieds. Parfois on peut le voir

(1) fouetté par saint Barthélémy;

(2) ordonné prêtre par saint Hedda de Winchester;

(3) avec des démons le molestant et des Anges le consolant. (Roeder).

On trouve au British Museum une magnifique Vita du 12ème siècle, illustrée, le

Harleian Roll Y.6, que l'on appelle habituellement le Guthlac Roll. C'est une

série de 18 ronds, des dessins pour vitrail, basés sur la Vita par Félix et

l'Histoire de Crowland par le pseudo-Ingulph.

Crowland a aussi plusieurs sculptures de sa vie datant du 13ème siècle. Le

sceau de l'abbé Henry de Crowland, 13ème siècle, montra Guthlac recevant un

fouet de saint Barthélémy pour écarter les attaques diaboliques (Farmer). Il

est vénéré dans le Lincolnshire (Roeder).

o "The Deserts of Britain"

o 4 endroits de lutte ascétique en Grande-Bretagne et les saints qui y oeuvrèrent : Saint Gwyddfarch, Sainte Melangell, Saint Cadfan, et Saint Guthlac

en anglais : http://www.nireland.com/orthodox/deserts.htm

Alternative Tinyurl: http://tinyurl.com/yq4rn

en français : http://www.amdg.be/sankt/deserts.htm

o Acathiste à notre saint père Guthlac (en anglais):

http://www.orthodoxengland.btinternet.co.uk/akaguth.htm

o "Saint Pega and Saint Guthlac in the South English Legendary"

par Alexandra H. Olsen

http://www.umilta.net/guthlac.html

SOURCE : http://home.scarlet.be/amdg/oldies/sankt/avr11.html

Scenes

from the life of Saint Guthlac showing the attack of the daemons.

Also

known as

Guthlac of Crowland

Guthlacus….

Guthlake….

formerly 12 April

30

August (translation of relics)

Profile

Born to the Mercian

nobility, the son of Penwald; brother of Saint Pega

of Peakirk. Soldier for

nine years in the army of King Ethelred

of Mercia; the freedom to loot led to him amassing a large forture. However,

in 697 he

had a conversion experience and gave up the violent life to become a Benedictine monk at

Repton under abbess Elfrida.

Known for his ascetic and strict habits. Hermit in

the Lincolnshire fens, living like the Desert Fathers in an inhospitable swamp

area rumoured to be the haunt of monsters and devils;

the abbey of Croyland was

built on the site of his hermit’s cell. Had

visions of angels, demons and Saint Batholomew,

to whom he had special devotion. Became friends with wild animals,

had the gift of prophecy, and his reputation for holines attracted many

would-be students including Saint Bettelin. Ordained by Bishop Hedda

of Winchester who

consecrated Guthlac’s cell as

a chapel so

he could celebrate Mass there.

Born

legend says that when he

was born, a shining hand surrounded by reddish-yellow light came down from

heaven and blessed the house

11 April 714 in

Croyland, England of

natural causes

initially buried, Saint Pega had

the body interred in a tomb

body found incorrupt

after a year

relics translated

to the re-built Croyland Abbey in 1136

relics translated

again in 1196

relics destroyed

in the 16th

century during the dissolution of the English monasteries

fighting a demon with

a scourge

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Legends

of Saints and Birds, by Agnes Aubrey Hilton

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Stories

of the Saints by Candle-Light, by Vera Barclay

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

images

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

MLA

Citation

“Saint Guthlac of

Croyland“. CatholicSaints.Info. 28 February 2024. Web. 10 April 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-guthlac-of-croyland/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-guthlac-of-croyland/

Roundel

from the Guthlac Roll depicting various benefactors to St Guthlac's shrine,

including King Æthelbald of Mercia, Abbot Thurketel and Earl Ælfgar, circa 1210

Guthlac of Croyland, OSB

Hermit (AC)

Born in Mercia, c. 673;

died at Crowland, Lincolnshire, England, in 714; feast day formerly on April

12; feast of his translation is August 30 and there is a commemoration on

August 26.

As a young man of royal

blood from the tribe of Guthlacingas, Guthlac had been a soldier for nine

years, fighting for Ethelred, the King of Mercia. At age 24, he renounced both

violence and the life of the world and became a monk in an Benedictine double

abbey at Repton, which was ruled by an abbess named Elfrida.

Even in these early years

his discipline was extraordinary. Some of the monks in fact disliked him

because he refused all wine and cheering drink. But he lived down the criticism

and gained the respect of his brothers. After two years in the monastery it

seemed to him far too agreeable a place. On the feast of Saint Bartholomew

about 701, he found a wet, remote, unloved spot on the River Welland in the

Fens, which could be reached only by boat, and lived there for the rest of his

life as a hermit, seeking to imitate the rigors of the old desert fathers.

His temptations rivalled

theirs. Wild men came out of the forest and beat him. Even the ravens stole his

few possessions. But Guthlac was patient, even with wild creatures. Bit by bit

the animals and birds came to trust him as their friend. A holy man named

Wilfrid once visited Guthlac and was astonished when two swallows landed on his

shoulders and then hopped all over him. Guthlac told him, "Those who

choose to live apart from other humans become the friends of wild animals; and

the angels visit them, too- -for those who are often visited by men and women

are rarely visited by angels."

Apparently, Guthlac was

also had a vision of Saint Bartholomew, his patron. Nor was he entirely alone

in his refuge: He had several disciples, Saints Cissa, Bettelin, Egbert, and

Tatwin, who had cells nearby. Bishop Hedda of Dorchester ordained him to the

priesthood during a visit. The exiled prince Ethelbald, often came to him for

advice, learned from Guthlac that he would wear the crown of the Mercians.

When he was dying,

Guthlac sent for his sister, Saint Pega, who was a hermitess in the same

neighborhood (Peakirk or Pega's church). Abbess Edburga of Repton sent him a

shroud and a leaden coffin. A year after his death, Guthlac's body was exhumed

and found to be incorrupt. Soon his shrine, to which his sister had donated his

Psalter and scourge, began popular. When both King Wiglaf of Mercia (827-840)

and Archbishop Ceolnoth of Canterbury (who was cured by Guthlac of the ague in

851) became devotees, Guthlac's cultus grew and spread. A monastery was

established on the site of Saint Guthlac's hermitage, which developed into the

great abbey of Crowland, to which his relics were translated in 1136. There was

another translation in 1196.

Guthlac's vita was recorded

in Latin by his near contemporary Felix. Several others were composed in Old

English verse and prose. Together with Saint Cuthbert, Guthlac was one of

England's most popular pre-Conquest hermit saints (Attwater, Benedictines,

Bentley, Farmer, Gill, Husenbeth).

In art, Saint Guthlac is

depicted holding a scourge in his hand and a serpent at his feet. At times he

may be shown (1) receiving the scourge from Saint Bartholomew; (2) being

ordained priest by Saint Hedda of Winchester; or (3) with devils molesting and

angels consoling him (Roeder). A magnificent pictorial record of his life

survives in the late 12th-century Harleian Roll Y.6 at the British Museum,

which is usually called the Guthlac Roll. This is a series of eighteen

roundels, cartoons for stained glass windows, based on Felix's vita and the

pseudo-Ingulph's history of Crowland.

Crowland also has several

13th-century sculptures of his life. Abbot Henry of Crowland's 13th-century

seal depicts Guthlac receiving a scourge from Saint Bartholomew for fending off

diabolical attacks (Farmer). He is venerated in Lincolnshire (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0411.shtml

Roundel

from the Guthlac Roll depicting Guthlac appearing to the Mercian king Æthelbald

in a dream, circa 1210

St. Guthlac

Hermit; born about 673;

died at Croyland, England,

11 April, 714. Our authority for the life of St. Guthlac is

the monk Felix (of

what monastery is

not known), who in his dedication of the "Life" to King

Æthelbald, Guthlac's friend, assures him that whatever he has

written, he had derived immediately from old and intimate companions of

the saint.

Guthlac was born of noble stock, in the land of the Middle Angles. In his

boyhood he showed extraordinary signs of piety;

after eight or nine years spent in warfare,

during which he never quite forgot his early training, he became filled with

remorse and determined to enter a monastery.

This he did at Repton (in what is now Derbyshire). Here after two

years of great penance and earnest application to all the duties of

the monastic life, he became fired with enthusiasm to emulate the wonderful penance of

the Fathers of the Desert. For this purpose he retired with two

companions to Croyland,

a lonely island in the dismal fen- lands of modern Lincolnshire. In this

solitude he spent fifteen years of the most rigid penance, fasting daily

until sundown and then taking only coarse bread and water. Like St. Anthony he

was frequently attacked and severely maltreated by the Evil

One, and on the other hand was the recipient of extraordinary graces and

powers. The birds and the fishes became his familiar friends, while

the fame of his sanctity brought

throngs of pilgrims to

his cell. One of them, Bishop Hedda (or Dorchester or

of Lichfield),

raised him to the priesthood and consecrated his humble chapel.

Æthelbald, nephew of the terrible Penda, spent part of his exile with the saint.

Guthlac, after his death,

in a vision to Æthelbald, revealed to him that he should

one day become king. The prophecy was verified in 716. During Holy

Week of 714, Guthlac sickened and announced that he should die on the

seventh day, which he did joyfully. The anniversary (11 April) has always

been kept as his feast. Many miracles were

wrought at his tomb,

which soon became a centre of pilgrimage.

His old friend, Æthelbald, on becoming king, proved himself a generous

benefactor. Soon a large monastery arose,

and through the industry of the monks,

the fens of Croyland became

one of the richest spots in England. The

later history of his shrine may be found in Ordericus

Vitalis (Historia Ecclesiastica) and in the "History of

Croyland" by the

Pseudo-Ingulph. Felix's Latin "Life" was turned

into Anglo-Saxon prose by some unknown hand. This version was first

published by Goodwin in 1848. There is also a metrical version

attributed to Cynewulf contained

in the celebrated Exeter Book (Codex Exoniensis).

Sources

Acta SS., XI, 37,

contains FELIX'S chronicle and extracts from ORDERICUS and the PSEUDO-INGULPH;

FULMAN, ed. Historia Croylandensis in R. S.; GOODWIN, Anglo-Saxon

Version of the Life of Guthlac (London, 1848); THORPE, Codex

Exoniensis (London, 1842); GOLLANCZ, The Exeter Book (London,

1895); GALE, edition of INGULPH, though old (1684), is still valuable.

Murphy, John F.X.

"St. Guthlac." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert

Appleton Company, 1910. 11 Apr. 2015

<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07092a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Bryan R. Johnson.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. June 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07092a.htm

Roundel from Guthlac Roll, depicting St Guthlac in contemplation, circa 1210

The

life of Saint Guthlac (Manuscript from the XIIth century, British Museum

Library Board -- Harley Roll Y.6 [1])

Das

Leben des heiligen Guhlac (Manuskript aus dem 12. Jahrhundert, British Museum

Library Board). H. W. Koch: Illustrierte Geschichte der Kriegszüge im

Mittelalter, S. 142, Bechtermünz Verlag, ISBN 3-8289-0321-5

St. Guthlake, Hermit, and

Patron of the Abbey of Croyland

HE 1 was

a nobleman, and in his youth served in the armies of Ethelred, king of Mercia:

but the grace of God making daily stronger impressions on his heart, in the

twenty-fourth year of his age he reflected how dangerous a thing it is to the

soul to serve in wars which too often have no other motive than the passions of

men and the vanities of the world, and resolved to consecrate the remainder of

his life totally to the service of the King of kings. He passed two years in

the monastery of Repandun, studying to transcribe the virtues and

mortifications of all the brethren into the copy of his own life. After this

novitiate in the exercises of an ascetic life, with the consent of his

superior, in 699, with two companions, he passed in a fisher’s boat into the

isle of Croyland, on the festival of St. Bartholomew, whom he chose for his

patron, and, by having recourse to his intercession, he obtained of God many

singular favours. Here he suffered violent temptations and assaults, not unlike

those which St. Athanasius relates of St. Antony: he also met with severe

interior trials; but likewise received frequent extraordinary favours and consolations

from God. Hedda, bishop of Dorchester, visiting him, ordained him a priest. The

prince Ethalbald, then an exile, often resorted to him, and the saint foretold

him the crown of the Mercians, to which he was called after the death of King

Coelred, in 719. The saint, foreknowing the time of his death, sent for his

sister Pega, 2 who

lived a recluse in another part of the fens four leagues off to the west. He

sickened of a fever, and on the seventh day of his illness, during which he had

said mass every morning, and on that day, by way of Viaticum, he sweetly slept

in our Lord, on the 11th of April, 714, being forty-seven years old, of which

he had passed fifteen in this island. See his life written by Felix, monk of

Jarrow, a contemporary author, from the relation of Bertelin, the companion of

the saint’s retirement, with the notes of Henschenius; 3 Mabillon,

Acta Bened. t. 3, p. 263, n. 1. See also his short English-Saxon life, Bibl.

Cotton. Julius, A. X.

Note

1. Called in the English Saxon language Guthlacer of Cruwland. [back]

Note

2. St. Pega is honoured on the 8th of January. Her cell, near Peakirk,

stood at the extremity of a high ground, which juts out into the fenny level,

where is the chapel of St. Pega’s monastery. Here passed Carsdike, so called

from Carausius. It was projected by Agricola, and perfected by Severus to carry

corn in boats for the army in the North. It was conducted from Peterborough

into the Trent at Torksey, below Burton, whence the navigation was carried on

by natural rivers to York. Carausius repaired it, and continued it on the

borders of the fenny level as far as Cambridge, which he built and called

Granta. This place was the head of the navigation, and Carausius instituted the

great fair when the fleet of boats set out with corn and other provisions,

which is still kept, with many of the ancient Roman customs, under the name of

Stourbridge fair. See Stukeley’s Medallic History of Carausius, t. 1, p. 172,

&c. t. 2, c. 5, p. 129. [back]

Note

3. Ingolphus, the great and learned abbot of Croyland, who died in

1109, wrote a book on the life and miracles of St. Guthlake, which is not now

extant. His accurate history of the abbey of Croyland, from the year 664 to

1091, was published by Sir Henry Saville, but far more complete and correct by

Thomas Gale, in 1684. In it he relates, p. 16, that in the year 851, Ceolnoth,

archbishop of Canterbury, by having recourse to the intercession of St.

Guthlake, was miraculously cured of a palsy, after his recovery had been

despaired of. This miracle the archbishop attested in a council of bishops and

noblemen, in the presence of King Bertulf: upon which occasion, all who were

present bound themselves by oath to perform a pilgrimage to the shrine of the

saint at Croyland. After this miracle, great numbers seized with the same

distemper recovered their health, by resorting thither from all parts of the

kingdom to implore the divine succour through the intercession of his servant.

Ethelbald, coming to the crown, had founded there a monastery. He had caused

great stakes and piles of oak to be driven into the ground in this swampy

place, and the quagmire to be filled up with earth brought from the country

called Upland, eight miles distant. This foundation being laid, he erected a

church of stone with a sumptuous monastery. This building was utterly destroyed

by the Danes in 870, of all the monks and domestics, only one boy escaping to

give the world an account of this massacre and devastation; in which the bodies

of Cissa, priest and hermit, St. Egbat, St. Tatwin, St. Bettelina, St.

Etheldrith, and others, were reduced to ashes. Some few monks still chose their

residence there among the ruins, till Turketil, the pious chancellor to King

Edred, in 946, rebuilt the abbey. This great man was cousin-german to three

brothers who were all successively kings, Athelstan, Edmund, and Edred, being

son of Ethelward, younger brother to their father Edward the Elder. To all

these three kings he had been chief minister at home, and generalissimo in all

their wars abroad, and had often vanquished the Danes and other enemies. When

Analaph had rebelled and usurped the kingdom of Northumberland, with a numerous

army of Danes, Norwegians, Scots, Picts, and Cumbrians, mostly idolaters, and

put King Athelstan to flight at Bruntford in Northumberland; Turketil rescued

him out of danger by defeating the enemy with his Londoners and Mercians, and

killing Constantine, king of the Scots. The Emperor Henry, Hugh, king of

France, and Lewis, prince of Aquitain, sent ambassadors with letters of

congratulation for this victory, and rich presents of spices, jewels, horses,

gold vessels, a part of the true cross, and of the crown of thorns in rich

cases, the sword of Constantine the Great, in the hilt of which was one of the

nails with which Christ was crucified, &c. Turketil was afterward sent by

King Athelstan to conduct his four royal sisters to their nuptials; the two

first to Cologne, to the Emperor Henry, where one married his son Otho, the

other one of his princes: the third he accompanied to King Hugh, whose son she

married; and the fourth was given in marriage to Lewis, prince of Aquitain. The

chancellor was enriched by these princes with many precious relics and other

presents; all which he afterward bestowed on the abbey of Croyland. Having long

served his country, and subdued all its enemies, he earnestly begged of King Edred

leave to resign his honours. The king, startled at the proposal, threw himself

at his feet, entreating him not to forsake him. Turketil, seeing his sovereign

at his feet, cast himself on the ground, and only rose to lift up the king: but

adjuring him by the Apostle St. Paul, (to whom the religious prince bore a

singular devotion,) he at length extorted his consent. Immediately he

dispatched a crier to proclaim through all the streets of London, that whoever

had any demands upon Turketil, he should repair to him on a day, and at a place

by him assigned, and he should be paid: and that if any one thought he had ever

been injured by him, upon his complaint, he should receive full satisfaction

for all damages, and three-fold over and above. This he amply executed: then

made over sixty of his manors to the king, and six to the monastery of

Croyland. Being accompanied thither by the king, he there took the monastic

habit, and was made abbot in 948. He restored the house to the greatest

splendour; and, having served God in it twenty-seven years, died of a fever in

975, in the sixty-eighth year of his age. It was his usual saying, which he

often repeated to his monks: “Preserve well the fire of your charity, and the

fervour of your devotion.” Croyland, pronounced Crouland, signifies a desert

fenny land. The monks, with incredible industry, rendered it fruitful, joined

the island to the continent, and raised several stupendous works about

it. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume IV: April. The Lives of the

Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/4/113.html

Roundel

from the Guthlac Roll, depicting Guthlac building a chapel at Crowland, circa 1210

Saint

Guthlac. Etching by G.F. Storm, 1842, after C.A. Stothard.

St. Guthlac

(c.AD 673-714)

St. Guthlac was the son

of Penwald, a minor prince from the Royal Mercian House of Icling, and his

wife, Tette. Born around AD 673, he was a serious child, not given to boyish

pranks. Yet upon reaching manhood at fifteen, he decided to become a soldier of

fortune. He collected a great troop of armed followers around him and,

together, they ravaged the countryside, burning, raping and pillaging as they

went. For nine years, Guthlac carried on with this thoughtless way of life

until, one night, he had a heavenly dream that instilled him with love and

compassion for his fellow man. He made an oath to dedicate his life to the

service of the Lord and, in the morning, bade his companions farewell. He

forsook his accumulated wealth and went off to join the dual-monastery at

Repton in Derbyshire, where he received the tonsure from Abbess Aelfthrith.

After two years in the

monastery, Guthlac began to long for the more secluded life of a hermit. So,

having acquired leave from the monastic elders, he departed for the great Fens,

north of Cambridge. Unlike the well drained arable land of today, the Fens were

then a labyrinth of black wandering streams, broad lagoons and quagmires with

vast beds of reeds, sedge and fern. The islands amongst this dismal swamp were

a great attraction for the recluse.

Guthlac was directed to a

particular one of these islands by a local man named Tatwin. Many people had

attempted to inhabit it before, but none had succeeded, on account of the

loneliness of the wilderness and its manifold horrors. The twenty-six year old

Guthlac eagerly rose to such a challenge and arrived in a little boat at his

new home of the "Crow Land" on St. Bartholomew's Day. He surveyed the

area a while before returning to Repton for supplies and building materials with

which he returned with the help of two servants. St. Guthlac found an ancient

tumulus on the island, against which he built himself a hermitage. He resolved

to wear only skins and ate only barley bread and drank water each day. For a

while, he was disturbed on his little island by a number of the native British

inhabitants who dragged him into the swamp and beat him. In the dark night,

Guthlac imagined he was attacked by horrible monsters. There were other dangers

closer to home however. Guthlac's servant, Beccel, was shaving him one day,

when he was seized by a desire to cut his master's throat and install himself

in his cell, that he might instead be honoured by the locals as a holyman.

Luckily, the perceptive Guthlac saw the temptation within and shamed the

offender into confession and repentance.

Guthlac was a tall trim

man. He was mild, engaging, tolerate, modest, patient and humble. These many

virtues were recognised by the Fenland wildlife. All the wild birds came to him

and fed from his hands. Ravens, though at first tormenting him by stealing

letters and gloves from his visitors, later, seized with compunction at his

reproofs, brought them back. As Wilfrid, a holy visitant, was once conversing

with him on his island, two passing swallows flew down onto the saint's

shoulders and burst into song. Guthlac believed that, "With him who has

led his life after God's will, the wild beasts and wild birds are tame."

After fifteen years in

the Fens, Guthlac was seized by an alarming illness while at prayers in his

chapel. Beccel ran to his side and tended him; but the holy man was dying. He

hung on for another eight days, giving his servant detailed instruction for his

burial by his sister, Pegge, in a lead coffin and a sheet given him by Abbess

Edburga. He died on 11th April AD 714 and the great Abbey of Croyland grew up

around his grave.

SOURCE : http://www.earlybritishkingdoms.com/adversaries/bios/guthlac.html

Legends

of Saints and Birds – Saint Guthlac and the Ravens

He of whom I write was a

hermit, who had his dwelling in desolate mid-England. This bleak fen district

was indeed the “dismal swamp,” where black streams wandered, oozing in stagnant

morasses round the roots of the alder and willow trees. Reed and sedge grew

there amidst the floating peat – all that remained of the vast forests of oak,

hazel, and yew, which had sunk beneath the sea as year upon year passed by.

Trees, torn down by flood and storm, dammed the waters back upon the land.

Will-o’-the-wisp lights shone forth by night, warnings which were needless, for

no travellers set foot in this land of marsh and mud, where even the sky seemed

less blue than in fairer climes.

Yet to this fen came

Guthlac, monk of the monastery of Repton, having permission to seek that

wilderness for which his soul longed. And he asked of one called Tatwin, who

dwelt on the edge of the fenland, whether he knew of any land in that morass

which might serve him for a dwelling. Then Tatwin told him that there was,

indeed, an island, yet because of its loneliness no man dare live there.

“Strange tales,” said Tatwin, “are told of this land. Demons torment those who

dwell there, making the dreary night a terror with their howlings.”

“I fear no demons,” answered

Guthlac, “so show me the way thither.”

So they rowed through the

fens until they came to the island called Crowland or Croyland, known to few

but Tatwin. On the Feast of Saint Bartholomew did Guthlac first see the place

where he was to dwell all his life.

Now, after he had settled

there he was tormented at night by strange noises; fierce-eyed, hairy men, with

teeth like horse-tusks, having crooked shanks and deformed feet, came to him.

And they tugged and pulled him from his hut, leading him to the fen, where they

let him sink in the dark waters, or dragging him through reed and thorn until

his body was torn and bleeding, or carrying him on great wings through the cold

regions of the air until he fell trembling and shivering, so chill he was.

These, then, were the demons of which Tatwin had spoken; yet some folk hold

them to have been naught evil, but simply the cries of the water-wolf, and the

moaning of the wind in the alder trees, which were thought to be the shrieks of

demons by those whom the marsh fever had laid low. And, maybe, the burning heat

and trembling cold of an ague fit caused Guthlac to imagine he was being

dragged through brambles or carried through the cold air. But he persevered and

dwelt on in that land.

Now, the wild birds of

the fens came to him, and he fed them. We are told how the ravens teased him,

for they came to steal from the men who sometimes came to Guthlac for the

teaching he was ever ready to give to them.

Over the fens came the

ravens, with their necks and feet drawn in; they floated high in the air,

steady and self-possessed, then on a sudden off they flew, swooping down upon

Guthlac and his friends.

“Cawruk! cawruk!” they

cried, then flew off with some treasure. But Guthlac told them that it was not

kind to do this, whereat the ravens listened, sitting upon the alder boughs,

and it seemed as if they understood the Saint, for after having communed with

each other, they flew down with what they had taken, giving it back to the

Saint. Therefore Guthlac praised the ravens, and the ravens bowed their heads

and flapped their wings, making obeisance to him.

Now, one day a holy man

named Wilfred came to visit Guthlac. He sat speaking with him on that island in

the dismal swamp, when the ravens came, as was their wont, crying “Cawruk!” And

Wilfred deemed those cries to bode evil, but Guthlac told him not so. “The

raven speaks but after his kind,” saith he, “and willeth no ill to any. The

good God gave them those hoarse voices and clothed them with sombre feathers.

Blessed be His Holy Name who hath given us eyes to see, and wit to perceive the

beauty of yonder raven’s wings as the sun shines upon them.” And another time

two swallows came to Guthlac, perching upon his shoulders. They lifted up their

voices, singing joyously. Then said Wilfred, for he chanced to be there again:

“I marvel at these birds.

Tell me wherefore comes it that the wild birds so tamely sit upon thee?”

To whom Guthlac made

reply:

“Hast thou not learned,

Brother Wilfred, in Holy Writ, that with him who has led his life after God’s

will the wild beasts and wild birds are tame?”

Thus dwelt Guthlac in the

fens. After his death monks came to the isle whereon he had dwelt, and driving

great piles deep into the morass, they built the great Abbey of Croyland that

abbey which became a sanctuary for all who were desolate and oppressed.

Wherefore let us give thanks to God who gave Guthlac grace to persevere, and

ourselves learn not to be lightly turned from well-doing. For had the Hermit

Guthlac forsaken this place where he proposed to lead a holy life, in prayer

serving God, because of night fears or marsh fever, the Abbey of Croyland would

not have been built.

– taken from Legends

of Saints and Birds by Agnes Aubrey Hilton

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/legends-of-saints-and-birds-saint-guthlac-and-the-ravens/

St.

Guthlac: the parish church of Astwick The exterior of this church shows that it

was once a cruciform church. The arch over the entrance was once the opening

into the south transept. This is the view from the roadside gate.

Miniature

Lives of the Saints – Saint Guthlake, Hermit

Article

Of royal birth, but of a

wild and adventurous disposition, Guthlake at the age of fifteen joined a

robber band, and became famous through the kingdom of Mercia for his daring

deeds. One night, after nine years of this life, as he lay awake in the forest,

new thoughts of death, the vanity of earth, and the joys of heaven stirred his

heart; whereupon, waking his companions, he bade them choose another chief, as

he had vowed himself to the service of Christ. Tearing himself from their

entreaties and embraces, he exchanged his arms for the dress of a rude peasant,

and humbly begged admittance into the abbey of Repton. There he did penance two

years, when, moved by the example of the desert Saints, he withdrew to the

marshes of Lincolnshire to lead a hermit’s life. In this solitude he suffered

the most terrible assaults from the evil spirits. They cast him into foul

swamps, reproached him incessantly with the sins ofhis youth, and once seemed

to have brought him to the mouth of hell itself. But Guthlake was stronger in

his weakness than in the most brilliant days of his youth. He prayed

constantly, and when quite worn out drove the devils off by the name of Jesus,

and made frequent acts of hope. He died, in 714, in the odour of sanctity, at

the age of forty-seven, and the famous abbey of Croyland rose over his grave.

Every good thought is the

whisper of grace in our hearts. Listen and instantly obey, lest you grieve and

extinguish the Holy Spirit of God.

How indispensably

necessary to me is Thy grace, O Lord, in order to begin, to continue, and to

accomplish what is good! For without it, I can do nothing; but in Thee I can do

everything by the strength of Thy grace. — Imitation of Christ

It was a dreary and

fearful waste to which God called Guthlake, but it became a holy and refreshing

sanctuary before he died. Morning and night an angel visited him, and whispered

the secrets of heaven to him as he knelt in prayer. The lower creatures obeyed

him. The birds and the fishes came at his call and ate out of his hand, while

the swallows would perch on his head and knees, and let him help them to build

their nests. To one who expressed surprise he said, “Know ye not that all

created beings unite themselves with him who unites himself with God?”

If you be willing, and

will hearken to Me, you shall eat the good things of the land. – Isaiah

1:19

MLA

Citation

Henry Sebastian Bowden.

“Saint Guthlake, Hermit”. Miniature Lives of the

Saints for Every Day of the Year, 1877. CatholicSaints.Info.

2 March 2015. Web. 10 April 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/miniature-lives-of-the-saints-saint-guthlake-hermit/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/miniature-lives-of-the-saints-saint-guthlake-hermit/

Іканапіс

XXI стагоддзя

Дызайн

Алены Мядзведзь. Іканапісцы Вольга Шаламава, Аляксандр Чашкін і Антон Дайнека

Peinture

d'icônes du 21e siècle

Conception par Alena Medvedz. Peintres d'icônes Olga Shalamova, Alexander Chashkin et Anton Daineka

Stamp of Belarus - 2018 - Colnect 767163 - Contemporary Icon Art in Belarus

Stamp

of Belarus - 2018 - Colnect 769947 - Saint Guthlac of Croyland

St Guthlac

of Crowland

April 11, 2009 by Mark Armitage

St. Guthlac holding the

whip given to him by St. Bartholomew and, a demon at his feet. (The statue from

the second tier of the Croyland Abbey's west front of the ruined nave; dates

from the XVth century).

Born of royal blood in

the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia around 673, Guthlac joined the army of King

Ethelred of Mercia aged fifteen – which in practice involved a good deal of

burning, raping and pillaging.

Aged twenty four, he

renounced military life and entered the double monastery (i.e. a monastery with

male and female wings) at Repton (in modern Derbyshire). His enthusiastic

asceticism (he spurned all alcoholic drink) earned him first the hostility and

later the respect of his brethren.

After a couple of years

he decided that the relative comfort of the monastery did not fulfil his

spiritual needs, and, seeking to imitate the lifestyle of the desert fathers of

old, he retired to Croyland (modern Crowland in Lincolnshire) –a wet, abandoned

and utterly miserable island in the River Welland in the East Anglian fens,

which in those times were a wilderness of black streams, meres and quagmires,

rank with reed and sedge and fern, in order to create for himself a very

English equivalent of the Egyptian desert.

In order to understand

the desert fathers (and hence Guthlac) we need first to appreciate their

theological presuppositions. For the desert fathers, Christ had won a decisive

victory in the war against Satan and his demons, but the skirmishing continued,

and the Church was constantly under attack from demons who, though the war was

lost, were determined to prolong the fighting.

Ascetics went out into

the desert because it was here that the demons could be directly confronted.

The primary purpose of this confrontation was not so much the personal

sanctification of the monk as the protection of the world which the monks had

left behind from demonic attack.

A figure like Guthlac,

accordingly, effectively left a worldly army (of sorts) in order to enlist in

spiritual army, and, in withdrawing into the remote wilderness of the Fens, he

was not so much escaping from the world as going out to do battle on behalf of

God’s Church.

His biographer Felix

(writing within living memory of Guthlac’s own life) recounts how he

constructed a cell out of a plundered barrow, dressed in animal skins and,

for his daily rations, consumed nothing more than a scrap of barley bread and a

small cup of muddy water after sunset (all of which inevitably led to

bouts of ague and marsh fever).

As if these self-inflicted

hardships were not sufficient, Guthlac was beaten up by wild men (at first

Guthlac thought they were monsters) – native Britons who dragged him off his

island and beat him up in the swamp – and he also had to endure the

depradations of the wild animals and birds who threatened his everyday

existence (crows and magpies stole what few possessions he had, and also stole

letters and gloves from his visitors).

Finally, however, in the

best tradition of the desert fathers, he befriended the birds and animals, to

the extent that a visiting holy man beheld two swallows landing on his

shoulders and hopping all over him. Guthlac is said to have remarked that

“those who choose to live apart from other humans become the friends of wild

animals; and the angels visit them, too – for those who are often visited by

men and women are rarely visited by angels”.

Guthlac was not entirely

alone in his Fenland wilderness, but, like the great desert fathers, aggregated

a group of disciples who inhabited cells nearby (Saints Cissa, Bettelin,

Egbert, and Tatwin). Bishop Hedda of Dorchester paid him a visit and ordained

him to the priesthood, and the exiled prince Ethelbald came to him for advice

(Guthlac prophesied – accurately – that Ethelbald would eventually wear the

Mercian crown).

Guthlac died in 714 in

the compamy of his sister Saint Pega (a local hermitess). A year later his

exhumed body was found to be incorrupt, and in the following century his shrine

became the centre of a growing cult visited by King Wiglaf of Mercia (827-840)

and Archbishop Ceolnoth of Canterbury (miraculously cured of ague by Guthlac in

851). A monastery grew up on the site of Saint Guthlac’s hermitage, and this in

turn evolved into Crowland Abbey, where his relics were brought in 1136.

SOURCE : https://saintsandblesseds.wordpress.com/2009/04/11/st-guthlac-of-crowland/

The parish church

of Crowland and, the west front of the ruined nave of the Croyland Abbey.

Wednesday 11 April 2012

St Guthlac, Warrior and Hermit

11 April is the anniversary of the death in 714 of St Guthlac, a soldier who

took up the life of a hermit at Crowland in the Lincolnshire fens, and

subsequently became one of Anglo-Saxon England's most important saints. Guthlac

was born into a noble Mercian family and began his life like any other

Anglo-Saxon nobleman, as a warrior; his was the Mercia of the

newly-discovered Staffordshire

Hoard, a kingdom of great wealth and power, and we might imagine Guthlac

carrying weapons adorned like this. Inspired by

"the valiant deeds of heroes of old", according to his biographer

Felix, Guthlac fought in the army of the king of Mercia, and spent his youth as

leader of a warband. And then one night, at about the age of twenty-four, he

went to bed brooding on his usual concerns:

[W]hen... Guthlac was

being storm-tossed amid the gloomy clouds of life's darkness, and amid the

whirling waves of the world, he abandoned his weary limbs one night to their

accustomed rest; his wandering thoughts were as usual anxiously contemplating

mortal affairs in earnest meditation, when suddenly, marvellous to tell, a

spiritual flame, as though it had pierced his breast, began to burn in this

man's heart. For when, with wakeful mind, he contemplated the wretched deaths

and the shameful ends of the ancient kings of his race in the course of the

past ages, and also the fleeting riches of this world and the contemptible glory

of this temporal life, then in imagination the form of his own death revealed

itself to him; and, trembling with anxiety at the inevitable finish of this

brief life, he perceived that its course daily moved to that end. He further

remembered that he had heard the words: 'Let not your flight be in the winter

neither on the sabbath day.' As he thought over these and similar things,

suddenly by the prompting of the divine majesty, he vowed that, if he lived

until the next day, he himself would become a servant of Christ.

Felix’s Life of Saint

Guthlac, trans. Bertram Colgrave (Cambridge, 1956), pp.81-3.

"He contemplated the wretched deaths and the shameful ends of the ancient

kings of his race in the course of the past ages, and also the fleeting riches

of this world and the contemptible glory of this temporal life" - in other

words, he lay in the dark and thought about the chief theme of Anglo-Saxon

heroic poetry, which is that earthly glory is splendid and beautiful but is

always passing into nothingness.

What stories did he reflect on, if Felix's description has any basis in reality? It would be wonderful to know. Perhaps the tales of his ancestors in the tribe of the Guthlacingas, or the kings of the royal line of Mercia - but those stories are all lost to us, and we can only speculate. Whatever it was, the sudden awareness of death brought about a great change in Guthlac: he gave up his military life and became first a monk at Repton and then a hermit at Crowland, exchanging battles with the king's enemies for fierce struggles against demons. His story was vividly brought to life by a later Crowland artist, working probably at the beginning of the thirteenth century, who produced a series of pictures illustrating Guthlac's life on a long roll of parchment (now British Library Harley Roll Y. 6). Above is Guthlac bidding farewell to a soldier's life; then we see him receiving the tonsure at Repton:

The Crowland artist has fudged the truth here in showing Guthlac receiving the

tonsure from a bishop; Repton was a double monastery (i.e. for men and women)

under the rule of an abbess, and the Life is clear that Guthlac

received the tonsure under Abbess Ælfthryth. I wrote about Repton, still a

fantastically evocative place for imagining Guthlac's Mercia, here.

Then we see Guthlac, looking pensive, arriving at Crowland in the wilds of the

Lincolnshire fens, on St Bartholomew's Day 699:

(Compare the same scene rendered in stone at Crowland). Guthlac established a hermitage for himself in an earthen mound, and there he underwent many trials, including being assailed by devils which were vividly imagined by the Crowland artist:

He overcame the devils with the help of St Bartholomew, his patron, and became a miracle-worker and counsellor to kings. You can see illustrations of all this in the Guthlac Roll.

After he died and was buried at Crowland, a monastery was later founded at the site of his hermitage. As well as the Life written by Felix, there are two Old English poems about him, and a post-Conquest account, produced by Orderic Vitalis at the direction of the monks of Crowland, who were ever enthusiastic workers in Guthlac's cause. This is what Crowland Abbey looks like today, a magnificent structure even now it's half in ruins:

Here, and at a number of other churches named for him in Lincolnshire, Guthlac

was long venerated. And thus, in fleeing glory, he won himself fame which has

lasted 1300 years.

SOURCE : https://aclerkofoxford.blogspot.com/2012/04/guthlac-warrior-hermit.html

Saint Guthlac, parish church

of Crowland, Lincolnshire.

San Guthlac Eremita

674 - 714

Nato principe nel regno

di Mercia, Guthlac, dopo una giovinezza avventurosa tra le armi, si convertì

alla vita monastica, distinguendosi per rigore ascetico e avversione all'alcol.

Attratto dalla vita eremitica, si stabilì in un'isoletta paludosa del Crowland,

dove condusse un'esistenza austera ispirata a Sant'Antonio Abate. Superate

prove e tentazioni, incluso l'attacco di misteriosi "mostri", Guthlac

acquisì fama per la sua santità e il dono della profezia, attirando visitatori

illustri come il vescovo Edda e il principe ereditario Atebaldo. La sua

biografia rimarca la sua imperturbabilità di fronte a rabbia, ansia e

tristezza. Presagendo la propria morte, invitò al funerale la sorella Santa

Pega. La sua tomba divenne meta di pellegrinaggi, alimentati dalla miracolosa

guarigione del vescovo Ceolnoth. Dedicatigli dieci luoghi di culto in

Inghilterra, le sue reliquie furono traslate nel 1136 nell'abbazia di Crowland,

eretta sul luogo della sua cella.

San Guthlac fu uno dei numerosi principi del regno inglese della Mercia ad essere elevati alla gloria degli altari. Nato nel 674, in giovane età con alcuni amici intraprese la carriera militare, compiendo così violenze e razzie. Quasi tutte le guerre in cui fu coinvolto, che si combatterono sul confine con il Galles, gli guadagnarono un invidiabile bottino, nonché la fama di grande condottiero. Trascorsi nove lunghi anni, arrivò per Guthlac il tempo della conversione che si concretizzò con l’ingresso nel monastero Repton nel Derbyshire. Secondo la “Vita” che narra la sua vicenda, il principe monaco si contraddistinse tra i suoi confratelli per l’ascetismo estremo e la profonda avversione all’alcolismo. Dopo due anni sentì però la chiamata alla vita eremitica ed a tal scopo gli fu proposto un luogo tanto lugubre a tal punto da essere odiato da tutti. Nel 699 si ritirò dunque con qualche compagno in questa isoletta delle paludi del Crowland per il resto della sua esistenza terrena. Assunse principalmente come modello di vita Sant’Antonio Abate, uno dei più grandi Padri del deserto.

Dovette superare numerose prove e tentazioni e subì l’attacco da dei cosiddetti “mostri”, identificanti probabilmente i discendenti dei britanni che si erano rifugiati in quella zona durante le invasioni dei sassoni. Divenuto famoso per la sua vita austera e per aver ricevuto il dono della profezia, si trovo a dover ricevere un numero sempre crescente di visitatori, tra i quali il vescovo Edda di Lichfeld, che lo ordinò sacerdote, ed il principe ereditario di Mercia Atebaldo. Dalla sua biografia si può notare come Guthlac non abbia mai manifestato rabbia, ansia o tristezza. Avendo predetto il giorno della propria morte, poté invitare al funerale sua sorella Santa Pega, anch’essa eremita.

Morto dunque nel 714, la sua tomba divenne immediatamente meta di pellegrinaggi

ed il fenomeno aumentò in seguito in seguito alla miracolosa guarigione dalla

malaria del vescovo Ceolnoth di Canterbury avvenuta nell’851. Una decina di

luoghi di culto gli furono dedicati in Inghilterra. Nel 1136 le sue reliquie

furono traslate nell’abbazia di Crowland, edificata ove sorgeva la sua cella.

San Guthlac è considerato uno degli eremiti inglesi più famosi della sua epoca.

Autore: Fabio Arduino

SOURCE : https://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/92326

Icon

of St Guthlac of Crowland

Den hellige Guthlac av

Croyland (~674-714)

Minnedag: 11.

april

Den hellige Guthlac (lat:

Guthlacus) ble født rundt 674 i Mercia i England. Han var sønn av Penwald og

hans hustru Tette og kom fra Mercia-grenen av slekten Guthlacinga og var av

kongelig blod og i slekt med kongehuset i Mercia. I sin barndom var han svært

alvorlig og viste uvanlige tegn på fromhet. Men da han var rundt 15 år, ble han

soldat i hæren til kong Ethelred av Mercia (675-704), og den sene

middelalderkatalogen over engelske helgener, Catalogus Sanctorum

Pausantium in Anglia fra 1200-tallet, kalte ham robustus depraedator.

I ni år hadde han stor

suksess i det som blir kalt en militær karriere, men som med større rett kan

beskrives som et liv viet til røveri og vold. Nesten alle hans kamper fant sted

langs grensen til Wales, og han bygde seg opp en stor formue. Han fikk åpenbart

ry som leder, for hans ledsagere kom fra alle kanter.

Men som 24-åring ga han i

697 opp dette livet etter en natt tilbrakt i kontemplasjon, og han bestemte seg

for å bli munk i Repton i det som nå er Derbyshire. Det var et dobbeltkloster

hvor noen konger av Mercia var gravlagt, styrt av abbedisse Elfrida (Ælfrith).

Da han avla løftene, ga han en tredjedel av sitt krigsbytte tilbake til ofrene.

Guthlacs biograf forteller at han var temmelig upopulær i begynnelsen på grunn

av sine strenge vaner, spesielt sin totale avholdenhet fra rusdrikker, men han

ble bedre likt etter hvert.

Etter et par år som munk

følte han imidlertid et kall til et liv i ensomhet i etterligning av

ørkenfedrene. Han fikk høre om et sted i The Fens i Lincolnshire som var så

dystert og hjemsøkt av onde ånder og monstre at ingen turde å bo der. Det var

Croyland (nå Crowland), et fuktig område ved en sving på elva Welland i The

Fens, et sted som bare kunne nås med båt. Navnet kommer fra gammelengelsk cru

lande, «vilt land».

Rundt 700 – legenden sier

at det skjedde på den hellige apostelen Bartolomeus'

minnedag den 24. august 699 – ble Guthlac eneboer der sammen med noen få

ledsagere. Han valgte Bartolomeus til sin skytshelgen og der bodde han resten

av livet, og hans liv lignet ørkenfedrenes. Ubehagelighetene inkluderte angrep

fra det han kalte «monstre», men som trolig var etterkommere etter keltiske

briter som hadde søkt tilflukt i The Fens under de saksiske invasjonene. Han

ble også utsatt for voldsomme fristelser fra djevler, men han ble trøstet av

visjoner av engler og sin skytshelgen Bartolomeus.

Som andre eneboere

utviklet Guthlac nære forbindelser med fugler og dyr, og han klaget ikke på de

tyvaktige vanene til kråker og skjærer, «for mennesker burde være et eksempel

på tålmodighet til og med for ville dyr». En hellig mann ved navn Wilfrid

besøkte en gang Guthlac og ble forbløffet da to svaler landet på skuldrene hans

og hoppet rundt på ham. Guthlac fortalte ham at «de som velger å bo borte fra

andre mennesker, blir venner med de ville dyrene; og englene besøker dem også,

for de som ofte blir besøkt av menn og kvinner, blir sjelden besøkt av engler».

Til tross for sin

isolasjon ble Guthlac berømt for sin askese og for sine profetiske evner, og

han fikk stadig flere besøkende. En av dem var den hellige biskop Hedda av Winchester,

som presteviet ham og konsekrerte hans beskjedne kapell. Hans biograf sier at

ingen noen sinne så ham sint, opphisset eller trist. Etter femten år som eremitt

visste han at døden nærmet seg i 714. Reptons abbedisse, den hellige Edburga av Repton,

skal ha sendt ham et likklede og en blykiste (selv om hennes dødsår vanligvis

angis til rundt 700). Han inviterte sin hellige søster Pega, som bodde som

eneboerske i det nærliggende Peakirk (= Pega's church), til sin begravelse. Dit

kom hun sammen med Guthlacs disipler, de hellige Cissa, Bettelin, Egbert

og Tatwin,

som bodde i celler i nærheten.

Guthlac døde den 11.

april 714 og ble gravlagt i jorden i all enkelhet, i henhold til hans eget

ønske. Men en kult startet øyeblikkelig, slik at hans søster Pega ønsket å

gravlegge ham på nytt på en mer passende måte. På årsdagen for begravelsen ble

graven åpnet, og Guthlacs legeme ble da funnet uten tegn til forråtnelse.

Guthlacs kult hadde sitt sentrum rundt hans grav i Croyland, hvor Pega hadde

gitt hans psalter og svøpe, som hun hadde arvet. Kong Ethelbald (Æthelbald) av

Mercia (716-57), som hadde vært en nær venn av den hellige, fikk graven bygd

opp og dekorert på passende vis. Allerede på Bartolomeusdagen i 716 la kong

Ethelbald ned grunnsteinen til et kloster til ære for Guthlac. Ethelbald hadde

besøkt Guthlac mens han var tronpretendent, og eneboeren hadde da profetert at

han ville bli rettmessig konge. Ethelbald avla da løfte om at han i tilfelle

ville bygge et kloster i Croyland, og dette løftet holdt han.

Den mest troverdige kilde

til informasjon om Guthlac finner vi i en biografi skrevet på latin mellom 730

og 740 av den angelsaksiske munken Felix – vi vet ikke hvilket kloster han kom

fra. Han dediserte biografien til Guthlacs venn, kong Ethelbald, og forsikret

ham at alt han hadde skrevet, hadde han hørt fra gamle og nære ledsagere av

Guthlac. Felix forteller at da den hellige ble født, steg en skinnende hånd

omgitt av et gulrødt lys ned fra himmelen og velsignet huset hvor han ble født

før den steg opp til himmelen igjen. Det ble også forfattet biografier på

gammelengelsk i prosa og vers.

Guthlac må nest etter den

hellige Cuthbert

av Lindisfarne regnes som den mest populære eremitten før den

normanniske invasjonen i 1066, men det må innrømmes at en rekke hendelser i

Felix' biografi ligner svært mye på episoder i den hellige abbed Antonius' liv og

i den hellige Beda

den Ærverdiges biografi om Cuthbert.

Guthlacs minnedag er 11.

april (tidligere 12. april), med en translasjonsfest den 30. august og en

minnedag (commemoratio) den 26. august. Kulten ble snart populær, og

blant dens tilhengere var kong Wiglaf av Mercia (827-40) og erkebiskop Ceolnoth

av Canterbury (833-70), som ble kurert for malaria av helgenen i 851. Festen

spredte seg snart over hele Mercia og til Westminster, St. Albans og Durham, og

ble etter hvert alminnelig i hele landet. Minst ni gamle kirker og et kloster

ble viet til ham.

Det opprinnelige

klosteret ble ødelagt av danskene i 870 og den hellige abbed Theodor og

hans store kommunitet ble myrdet mens de feiret messe. Det neste klosteret ble

brent ned i 1091. Det tredje klosteret på stedet ble påbegynt i 1113, men ble

delvis ødelagt av et jordskjelv i 1118 og en brann i 1143. Guthlacs relikvier

hadde i 1136 blitt overført til den klosterkirken som ble bygd på stedet for

hans celle, og skrinet ble utsmykket med gull, sølv og juveler. En annen

translasjon fant sted i 1196. Et segl som tilhørte Henrik de Longchamp, abbed

av Croyland mellom 1191 og 1236, viser apostelen Bartolomeus som gir Guthlac en

svøpe. Denne var ikke for selvpisking, men for bruk som et defensivt og offensivt

våpen mot djevelske angrep. Klosteret ble delvis revet ned etter oppløsningen

av klostrene under kong Henrik VIIIs (1509-47) reformasjon på 1500-tallet. Bare

nordskipet, som i dag brukes som sognekirke, og klokketårnet er bevart.

Guthlacs grav ble så fullstendig ødelagt at det aldri siden ble funnet noen

spor av den eller av relikviene.

Et unikt billedmateriale

fra Guthlacs liv er bevart på British Museum. Den kalles «Harleian Roll Y.6»

eller vanligvis «Guthlac-rullen» og er en velum-rull med 17 ½ runde bilder som

hvert er rundt 15 cm i diameter. De viser scener fra hans liv og stammer fra

andre halvdel av 1100-tallet. Rullen ble trolig laget for abbeden i Croyland og

bildene kan ha vært skisser til glassmalerier. En skulptur i klosteret i

Crowland viser Guthlac som holder en pisk og med en slange ved sine føtter.

Kilder: Attwater/John,

Attwater/Cumming, Farmer, Bentley, Butler (IV), Benedictines, Bunson, Cruz (1),

KIR, CE, CSO, Patron Saints SQPN, Infocatho, earlybritishkingdoms.com,

churchmousewebsite.co.uk, peterborough.net - Kompilasjon og oversettelse:

p. Per Einar

Odden - Opprettet: 1998-05-06 00:13 -

Sist oppdatert: 2006-01-01 17:22

SOURCE : http://www.katolsk.no/biografier/historisk/guthlac

Voir aussi : http://www.umilta.net/pega.html