Bienheureux Georges HAYDOCK

Nom: HAYDOCK

Prénom: Georges

Pays: Grande Bretagne

Naissance:

Mort: 1584

Etat: Prêtre - Martyr du Groupe des 85

martyrs de Grande Bretagne (1584-1679) 2

Note:

Béatification: 22.11.1987 à Rome par Jean

Paul II

Canonisation:

Fête: 12 février (4 mai)

Réf. dans l’Osservatore Romano: 1987 n.48

Réf. dans la Documentation Catholique: 1988 p.59

& 127

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/hagiographie/fiches/f0294.htm

Bienheureux Thomas Hemmeford, Jacques Fenn, Jean Nutter, Jean Munden et Georges Haydock, prêtres et martyrs

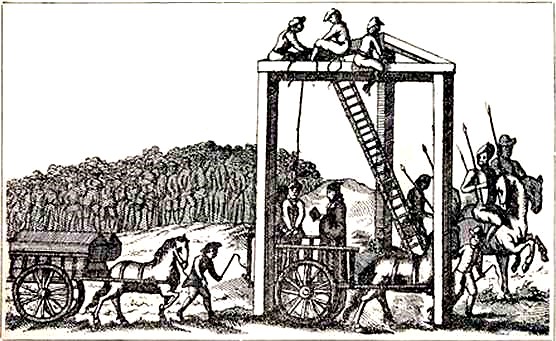

Sous la reine Elisabeth Ière, ces prêtres catholiques furent condamnés, suppliciés et éviscérés à Tyburn, près de Londres, en 1584 pour leur fidélité à la sainte Église romaine.

Plaque honouring Blessed George Haydock in St. Andrew's & Blessed George Haydock's Catholic Church, Cottam, Lancashire, UK.

Blessed George Haydock

- 12 February

- 22 November as one of the Martyrs of England, Scotland, and Wales

- 29 October as one of the Martyrs of Douai

Profile

Youngest son of Evan and

Helen Haydock. Educated at the English College in Douai, France, and the English College in Rome, Italy. Ordained on 21 December 1581 at Rheims, France. He then returned to England to minister to covert Catholics during the persecutions of Queen Elizabeth I. Arrested in London, England, he served 15 months in the Tower

of London for the crime of being a priest; at one point he was finally allowed to

administer the Sacraments to fellow prisoners. Zealous supporter of the pope, and not secular authorities, as ruler of the Church. One of

the Martyrs of

England, Scotland, and Wales.

- hanged, drawn and

quartered on 12 February 1584 in Tyburn, London, England

- 10 November 1986 by Pope John Paul II (decree of martyrdom)

Additional Information

- 105 Martyrs

of Tyburn

- Catholic

Encyclopedia

- Mementoes of the English Martyrs and Confessors, by Father Henry Sebastian Bowden

- Saints of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

- books

- A Calendar of the English Martyrs of the

Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

- Book of Saints, by the Monks of Ramsgate

- Our Sunday Visitor’s

Encyclopedia of Saints

- other

sites in english

- sitios

en español

- Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

- fonti

in italiano

- Cathopedia

- Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

- Santi e

Beati

- nettsteder

i norsk

Readings

I pray God that my blood may increase the Catholic faith in England. – Blessed George, speaking from the

gallows

MLA Citation

- “Blessed George

Haydock“. CatholicSaints.Info. 18 May 2020. Web. 12 February

2021. <https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-george-haydock/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-george-haydock/

On November 22, 1987, Pope John Paul II beatified Blessed George

Haydock and 84 other men who died for their faith in England during

the Reformation. The rite of beatification at St. Peter's in Rome was a notable

British celebration. A large delegation from England and Wales was on hand: 32

bishops, 300 priests, and a crowd of layfolk, including blood descendants of 12

of the new “blesseds”.

The beatification crowned a study of the

deaths of the 85 candidates that had lasted for 12 years, and had produced

seven volumes of information, totaling 2667 pages, about their lives and deaths.

The time of these martyrdoms extended from

1584, when Bl. William Carter, a printer, was hanged, until 1679, when the last

of the 85 died on the scaffold - Blessed Charles Meehan, an Irish Franciscan

priest. Most of the group were diocesan priests; a few like Blessed Charles

belonged to religious orders; and 22 were laymen of various estate: landowners,

teachers, a bartender, a stableboy, etc

As they represented every level of

society, so they represented every adult age from the 20's to the 80's. The

government books declared that they had been executed for “treason” or

“felony”. What the historical investigation proved was that the priests'

“treason” was simply that they had been ordained as priests and went about

Britain fulfilling their priestly duties. A law of 1585 had declared that any

Catholic priest who ministered in England was by that fact a traitor, deserving

of hanging.

The non-priests of the group were not

condemned for treason, but for aiding these “traitors”. They had opened their

homes to the Catholics for Mass; they had hidden the priests from the police;

they had done them a thousand loyal services to show their devotion and

gratitude. They had, so to speak, offered these “apostles” a “cup of cold

water”. But this sort of aid to priests was a felony according to the

anti-Catholic law; and felony, too, was punishable by death. These laity,

therefore, collaborated gladly with the clergy for the glory of God, even to

the point of sharing death with them.

When the new list of blesseds was

announced, some asked why no women were among them. Certainly there were women

- over 20 of them - who suffered for their Catholic faith, some of them the

wives of those who were executed. Three of these women have already been

canonized, and one beatified. But these four had been executed. Generally,

British law felt a delicacy about executing women. Therefore, most of the

Catholic women who died for the faith died in prison; and it is harder to judge

in those cases whether they are to be considered as “martyrs” or “confessors”

(tortured for the faith, but not executed).

Another question raised was the effect of

the beatifications on ecumenical relations. Would it not alienate the

Anglicans, whose heads, the queen (or king) were responsible for the Catholic

martyrs' deaths? Or was it fair to proclaim Catholic martyrs while saying

nothing of the 200 Protestants who were executed for religious reasons by

Catholic Queen Mary Tudor? After all, Vatican II declared that the human person

should never be forced to act against his conscience (Declaration of Religious

Liberty, 2).

If complaints have been made in the past

about beatifications of English Catholic Reformation martyrs, these criticisms

were mostly absent in the present case. Sincere ecumenical dialogue between

Catholics and Anglicans since Vatican II has changed the whole outlook. This time

the Church of England even sent a bishop to represent it at the beatification

ceremony. This time, too, Archbishop Robert Runcie, Anglican primate of

Canterbury, and Cardinal George Basil Hume, Catholic archbishop of Westminster,

answered the question in a joint statement. They prayed together, “God our

Father, giver of all peace and concord, forgive the sins which we have

committed against each other, heal our divisions and bring us to peace and

unity through the prayer of your Son, Jesus Christ our Lord.”

--Father Robert F. McNamara

Ven. George Haydock

English martyr; born 1556; executed at Tyburn, 12 February, 1583-84. He was the youngest son of Evan Haydock of Cottam Hall, Lancashire, and Helen, daughter of William Westby of Mowbreck Hall, Lancashire; was educated at the English Colleges at Douai and Rome, and ordained priest (apparently at Reims), 21 December, 1581. Arrested in London soon after landing, he spent a year and three months in the strictest confinement in the Tower, suffering from the recrudescence of a severe malarial fever first contracted in the early summer of 1581 when visiting the seven churches of Rome. About May, 1583, though he remained in the Tower, his imprisonment was relaxed to "free custody", and he was able to administer the Sacraments to his fellow-prisoners. During the first period of his captivity he was accustomed to decorate his cell with the name and arms of the pope scratched or drawn in charcoal on the door or walls, and through his career his devotion to the papacy amounted to a passion. It therefore gave him particular pleasure that on the following feast of St. Peter's Chair at Rome (16 January) he and other priests imprisoned in the Tower were examined at the Guildhall by the recorder touching their beliefs, though he frankly confesses it was with reluctance that he was eventually obliged to declare that the queen was a heretic, and so seal his fate. On 5 February, 1583-4, he was indicted with James Fenn, a Somersetshire man, formerly fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, the future martyr William Deane, who had been ordained priest the same day as himself, and six other priests, for having conspired against the queen at Reims, 23 September, 1581, agreeing to come to England, 1 October, and setting out for England, 1 November. In point of fact he arrived at Reims on 1 November, 1581. On the same 5 February two equally ridiculous indictments were brought, the one against Thomas Hemerford, a Dorsetshire man, sometime scholar of St. John's College, Oxford, the other against John Munden, a Dorsetshire man, sometime fellow of New College, Oxford, John Nutter, a Lancashire man, sometime scholar of St. John's College, Cambridge, and two other priests. The next day, St. Dorothy's Day, Haydock, Fenn, Hemerford, Munden, and Nutter were brought to the bar and pleaded not guilty.

Haydock had for a long time shown a great devotion to St. Dorothy, and was accustomed to commit himself and his actions to her daily protection. It may be that he first entered the college at Douai on that day in 1574-5, but this is uncertain. The "Concertatio Ecclesiae" says he was arrested on this day in 1581-2, but the Tower bills state that he was committed to the Tower on the 5th, in which case he was arrested on the 4th. On Friday the 7th all five were found guilty, and sentenced to death. The other four were committed in shackles to "the pit" in the Tower, but Haydock, probably lest he should elude the executioner by a natural death, was sent back to his old quarters. Early on Wednesday the 12th he said Mass, and later the five priests were drawn to Tyburn on hurdles; Haydock, being probably the youngest and certainly the weakest in health, was the first to suffer. An eyewitness has given us an account of their martyrdom, which Father Pollen, S.J., has printed in the fifth volume of the Catholic Record Society.

He describes Haydock as "a man of complexion fayre, of countenance milde, and in professing of his faith passing stoute". He had been reciting prayers all the way, and as he mounted the cart said aloud the last verse of "Te lucis ante terminum". He acknowledged Elizabeth as his rightful queen, but confessed that he had called her a heretic. He then recited secretly a Latin hymn, refused to pray in English with the people, but desired that all Catholics would pray for him and his country. Whereupon one bystander cried "Here be noe Catholicks", and another "We be all Catholicks"; Haydock explained "I meane Catholicks of the Catholick Roman Church, and I pray God that my bloud may encrease the Catholick faith in England". Then the cart was driven away, and though "the officer strock at the rope sundry times before he fell downe", Haydock was alive when he was disembowelled. So was Hemerford, who suffered second. The unknown eyewitness says, "when the tormentor did cutt off his members, he did cry, 'Oh! A!'; I heard myself standing under the gibbet". As for Fenn, "before the cart was driven away, he was stripped of all his apparell saving his shirt only, and presently after the cart was driven away his shirt was pulled of his back, so that he hung stark naked, whereat the people muttered greatly". He also was cut down alive, though one of the sheriffs was for mercy. Nutter and Munden were the last to suffer. They made speeches and prayers similar to those uttered by their predecessors. Unlike them they were allowed to hang longer, if not till they were dead, at any rate until they were quite unconscious. Haydock was twenty-eight, Munden about forty, Fenn, a widower, with two children, was probably also about forty, Hemerford was probably about Haydock's age; Nutter's age is quite unknown.

Sources

GILLOW, Bibl. Dict. Eng. Cath.,

III, 202; cf. III, 265; V, 142, 201; CATHOLIC RECORD SOCIETY, publications

(London, 1905-), II, V, passim, III, 12-15; IV, 74; FOLEY, Records Eng.

Prov. S.J., VI (London, 1875-1883), 74, 103; BRIDGEWATER, Concertatio

Ecclesiae Catholicae (Trier, 1588), passim; WAINEWRIGHT in CATHOLIC

TRUTH SOCIETY's pamphlets: George Haydock; James Fenn; John Nutter; Two

English Martyrs; POLLEN, Acts of English Martyrs (London,

1891), 252, 253, 304.

Wainewright, John. "Ven. George

Haydock." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York:

Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 27 Nov.

2020 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07159a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was

transcribed for New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. Honoribus altaris, Rex

martyrum Domine, glorifica servum tuum.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil

Obstat. June 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07159a.htm

St. Andrew's & Blessed George Haydock's Catholic Church. Built during the Recusant era in 1790 and still in operation. Haydock's name was added after his beatification in 1987. Cottam, Lancashire, UK

THE MARTYRDOM OF BLESSED GEORGE HAYDOCK:

"Sadness turned into Joy"

by Barry Coldrey and Leo Griffin

(Melbourne, 2001. Available from Tamanaraik Press,

7/67 Collins Street, Thornbury, Vic, 3071, tel (03) 9480 2119. Spiral bound,

$9.95 post free)

This is the third book in a series of modern lives of the English martyrs, commenced by Br Leo Griffin CFC 10 years ago. The first was a Life of St Margaret Clitherow, published in 1992, and the second, The Life of St Philip Howard, Martyr, released in 1998.

On this occasion, Br Griffin is joined by another author, and fellow Christian Brother, in completing the work, as advancing years and arthritis have taken some toll.

During penal times in Elizabethan England the principal stronghold of the Catholic survivors of persecution and repression was the county of Lancashire where a cluster of reasons guaranteed the survival of the Old Faith.

Lancashire was a large, sparsely-populated county remote from the wealth and commerce of the south- east and distant from the seat of government in London.

However, the principal reason for the survival of

Catholicism was the strength of the Catholic gentry.

The Haydocks were Lancashire gentry, their estates centred on Cottam, near Preston. Their forbears had been prominent in the political and social life of the county for generations. In the religious turmoil of the 16th century the family remained firmly Catholic through trial and persecution.

This account is focused on the story of Blessed George Haydock, the martyr, but there were three priests from the family ministering during Elizabeth's reign - George himself, his father, Vivian, and his older brother, Richard.

In the "lives" a little piece of 16th-century England comes alive, on the one hand its excitement and splendour - it is the age of Shakespeare and exploration of the New World of the Americas - and, on the other, the reality of its awfulness and tragedy.

In spite of the risks of capture, imprisonment, torture and a gruesome death, there was no shortage of vocations to the priesthood.

During Queen Elizabeth I's reign (1558-1603), 815 young Englishmen fled England to be trained as priests in continental seminaries; 547 were ordained and returned to England secretly, of whom more than one-half were captured and imprisoned and between 120-130 of them were executed. And 60 lay men and women were executed for assisting priests in some way.

While the story focuses on the Haydock family, there are many vignettes of life in the English Church in penal times.

There was Mistress (Mrs) Margaret Line who managed a secret hostel in London for some years for priests who came to the capital on business. Eventually she was caught and condemned to death for "harbouring a priest". "Pity it wasn't a thousand," she remarked to the judge.

There were the Vaux sisters whose vast semi-fortified mansion at Badderly Clinton in a remote part Warwickshire was used for priests' meetings and retreats.

There is the finance officer in the municipality of Newcastle-on- Tyne outlining the substantial costs of arranging an execution of a priest and keen on finding cheaper suppliers.

This is an interesting portrait of the English-speaking Church in an heroic age.

The

One Hundred and Five Martyrs of Tyburn – 12 February 1584

Venerable James Fenn, secular priest

Venerable George Haydock, secular priest

Venerable Thomas Hamerford, secular priest

Venerable John Munden, secular priest

Venerable John

Nutter, secular priest

On the Feast of Saint Peter’s Chains, these prisoners

of Christ were accounted worthy to hear the death sentence passed on them for

upholding the primacy of Peter.

James Fenn was born at Montacute, in Somersetshire. He

made his studies at Oxford, at New College and Corpus Christi College. On the

death of his wife he became a Seminary Priest. A moving scene took place at the

Tower Gate after he was bound on the hurdle; his little daughter Frances, with

many tears, came to take her last leave of him and receive his blessing, which

he gave her with difficulty, striving to raise his manacled hands.

George Haydock, the son of the Squire of Cottamhall,

near Preston, Lancashire was the youngest of the five martyr priests, being

only twenty-four years old when he suffered. In answer to the questions put by

the minister, he said that if he and the Queen were alone in some desert place

where he could do to her what he would he would not so much as prick her with a

pin: “No, not to gain the whole world, and,” he added, “I beg and beseech all

Catholics to pray together with me to our common Lord for me and for our

Country’s weal.”

Venerable Thomas Hamerford and Venerable John Munden

welcomed death with great fortitude. Father Munden acknowledged his sentence by

joyfully reciting the “Te Deum.” They were both natives of Dorset.

Venerable John Nutter was born in Lancashire. He won

for himself the name “John of Plain Dealing” from his fellow prisoners for his

outspokenness in rebuking vice. He is said to have been timid by nature, but he

now met a most cruel death with no less courage and constancy than his

companions.

– from The One Hundred

and Five Martyrs of Tyburn, by The Nuns of the Convent of

Tyburn, 1917

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/the-one-hundred-and-five-martyrs-of-tyburn-12-february-1584/

Mementoes

of the English Martyrs and Confessors – Venerable George Haydock, Priest, 1584

Article

He was the son of Verran Haydock, the representative of an ancient Catholic family of Cottam Hall, Lancashire; his mother, a Westby of Westby, York. When on her deathbed, to console her sorrowing husband, she pointed, with the infant George in her arms, to the motto embroidered at the foot of the bed, “Tristitia vestra in gaudium vertetur.” (“Your sorrow shall be turned into joy.”) But the joy prophesied was not to be of this world. The widowed husband, seeing how persecution was ravaging the Church in England, to offer some reparation made over his property to his son William, and went over to Douay with the two others, Richard and George, all three to be trained for the priesthood. The father became procurator of the Douay College in England, and filled the office with great success. Richard after varied missionary work died in Rome, and George returned to England as a priest in February 1581, and was betrayed on arriving by an old tenant of his father’s who had apostatised. His aged father on the previous All Souls Eve, when about to say the accustomed midnight Mass, seemed to see his son’s severed head above the altar, and to hear the words, “Tristitia vestra, etc.,” and, swooning away, gave back his soul to God to find his sorrow turned to joy.

Arrested as a priest in February 1582 in Saint Paul’s

Churchyard, he was confined in the Tower, where he was robbed of all his money,

and suffered much from the hardships of his imprisonment, and from a lingering

disease that he had contracted in Italy. On 7 February 1583, he was sentenced

to death for having been made priest by the Pope’s authority beyond the seas.

He attributed this happy event to the prayers of Saint Dorothy, Virgin and

Martyr, whose day it was, and he marked it in the Calendar of his Breviary,

which he left to Dr. Creagh, Archbishop of Armagh, then a prisoner in the

Tower. But to his sorrow he heard that the Queen had changed her mind, and that

he was not to suffer. His Confessor, however, a man of great experience,

encouraged him by the assurance that these rumours were industriously spread

abroad only to represent the Queen as averse from these cruelties, and to

remove any odium from her, as if they were extorted from her against her

inclinations. The falseness of the Queen’s reported leniency was proved by the

event. Father Haydock, without a sign of any pardon, was hung at Tyburn, and

the whole butchery performed 12 February 1584.

MLA Citation

Father Henry Sebastian Bowden. “Venerable George

Haydock, Priest, 1584”. Mementoes of the English

Martyrs and Confessors, 1910. CatholicSaints.Info.

21 April 2019. Web. 12 February 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/mementoes-of-the-english-martyrs-and-confessors-venerable-george-haydock-priest-1584/>

Beato Giorgio Haydock Sacerdote e martire

>>>

Visualizza la Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

Lancashire, 1556 – Londra, 12 febbraio 1584

Londinese del Lancashire, dove era nato nel 1556,

Giorgio Haydock studiò a Douai, in Francia e a Roma e venne ordinato sacerdote

il 21 dicembre 1581. Partì per l'Inghilterra come missionario «seminarista»,

come erano allora chiamati gli inglesi che si recavano all'estero per studiare

e ritornare poi a riconvertire i loro connazionali. Arrivato a Londra il 6

febbraio 1582 venne subito scoperto ed arrestato e chiuso nella famosa Torre,

dove visse al buio e in grande solitudine per un anno e tre mesi. Rimesso in un

regime carcerario più leggero, ebbe la possibilità di confortare e amministrare

i sacramenti ai suoi compagni di prigionia. Venne nuovamente denunciato insieme

ad altri e il 12 febbraio 1584 fu impiccato; anche a lui fu riservata

l'orribile fine di essere sciolto dal cappio ancora vivo e sventrato. È stato

beatificato a Roma da Giovanni Paolo II il 22 novembre 1987.

La storia delle persecuzioni anticattoliche in Inghilterra, Scozia, Galles, parte dal 1535 e arriva al 1681; il primo a scatenarla fu com’è noto il re Enrico VIII, che provocò lo Scisma d’Inghilterra con il distacco della Chiesa Anglicana da Roma.

Artefici più o meno cruenti furono oltre Enrico VIII, i suoi successori Edoardo VI (1547-1553), la terribile Elisabetta I, la “regina vergine” († 1603), Giacomo I Stuart, Carlo I, Oliviero Cromwell, Carlo II Stuart.

Morirono in 150 anni di persecuzione, migliaia di cattolici inglesi appartenenti ad ogni ramo sociale, testimoniando il loro attaccamento alla fede cattolica e al papa e rifiutando i giuramenti di fedeltà al re, nuovo capo della religione di Stato.

Primi a morire come gloriosi martiri, il 4 maggio e il 15 giugno 1535, furono 19 monaci Certosini, impiccati nel tristemente famoso Tyburn di Londra, l’ultima vittima fu l’arcivescovo di Armagh e primate d’Irlanda Oliviero Plunkett, giustiziato a Londra l’11 luglio 1681.

L’odio dei vari nemici del cattolicesimo, dai re ai puritani, dagli avventurieri agli spregevoli ecclesiastici eretici e scismatici, ai calvinisti, portò ad inventare efferati sistemi di tortura e sofferenze per i cattolici arrestati.

In particolare per tutti quei sacerdoti e gesuiti, che dalla Francia e da Roma, arrivavano clandestinamente come missionari in Inghilterra per cercare di riconvertire gli scismatici, per lo più essi erano considerati traditori dello Stato, in quanto inglesi rifugiatosi all’estero e preparati in opportuni Seminari per il loro ritorno.

Tranne rarissime eccezioni, come i funzionari di alto rango (Tommaso Moro, Giovanni Fisher, Margherita Pole) decapitati o uccisi velocemente, tutti gli altri subirono prima della morte, indicibili sofferenze, con interrogatori estenuanti, carcere duro, torture raffinate come “l’eculeo”, la “figlia dello Scavinger”, i “guanti di ferro” e dove alla fine li attendeva una morte orribile; infatti essi venivano tutti impiccati, ma qualche attimo prima del soffocamento venivano liberati dal cappio e ancora semicoscienti venivano sventrati.

Dopo di ciò con una bestialità che superava ogni limite umano, i loro corpi venivano squartati ed i poveri tronconi cosparsi di pece, erano appesi alle porte e nelle zone principali della città.

Solo nel 1850 con la restaurazione della Gerarchia Cattolica in Inghilterra e Galles, si poté affrontare la possibilità di una beatificazione dei martiri, perlomeno di quelli il cui martirio era comprovato, nonostante i due - tre secoli trascorsi.

Nel 1874 l’arcivescovo di Westminster inviò a Roma un elenco di 360 nomi con le prove per ognuno di loro. A partire dal 1886, i martiri a gruppi più o meno numerosi, furono beatificati dai Sommi Pontefici, una quarantina sono stati anche canonizzati nel 1970.

Per altri 85 nel 1987, si sono conclusi gli adempimenti necessari e così il 22 novembre 1987 papa Giovanni Paolo II li ha beatificati a Roma, con il capofila Giorgio Haydock, confermando il giorno della loro celebrazione al 4 maggio.

Di essi 63 sono sacerdoti, di cui 2 gesuiti, 1 domenicano, 5 francescani e 55

diocesani; gli altri 22 sono laici, fra cui il tipografo William Carter.

GIORGIO HAYDOCK nacque nel 1556 a Lancashire, studiò a Douai (Francia) e

Roma e fu ordinato sacerdote il 21 dicembre 1581.

Partì per l’Inghilterra come missionario ‘seminarista’, come erano allora chiamati gl’inglesi che si recavano all’estero per studiare e ritornare poi a riconvertire i loro connazionali. Arrivato a Londra il 6 febbraio 1582 venne subito scoperto ed arrestato quindi chiuso nella famosa Torre, dove visse nel buio e in grande solitudine per un anno e tre mesi.

Rimesso in un regime carcerario più leggero, ebbe la possibilità di confortare e amministrare i Sacramenti ai suoi compagni di prigionia.

Venne denunciato di nuovo insieme ad altri e il 12 febbraio 1584 venne impiccato; anche a lui fu riservata l’orribile fine di essere sciolto dal cappio ancora vivo e sventrato.

Autore: Antonio Borrelli

Beati Martiri Inglesi Beatificati nel 1987

>>> Visualizza la Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

George Haydock e 84 compagni furono beatificati da Papa Giovanni Paolo II il 22 novembre 1987.

Durante il periodo che va dal 1535 al 1681 la persecuzione religiosa fu molta diffusa in Inghilterra, Galles e Scozia. Fin da quel tempo di persecuzione, i cattolici che diedero la loro vita per la fedeltà a Cristo e alla Chiesa vennero considerati come martiri. Come tali, essi furono venerati segretamente nel Regno Unito - ancora in stato di persecuzione - e più apertamente all'estero.

All'origine delle cruente persecuzioni contro i cattolici inglesi del secolo XVI e XVII sta lo scisma d'Inghilterra, provocato da Enrico VIII con l'Atto di supremazia del 3 novembre 1534. Questo solco scavato tra Roma e Londra venne poi approfondito dalle riforme anticattoliche di Edoardo VI (1547-1553) e, dopo un fragile periodo di restaurazione cattolica da parte di Maria Tudor (1553-1558), di Elisabetta (1558-1603), che dimostrò un implacabile odio antiromano. Fu proibita la messa con l'Atto di uniformità (1559), furono imposte le idee luterane e calviniste con i 39 articoli del 1563 e la dottrina cattolica fu proclamata un coacervo di superstizioni e di pratiche idolatriche. Furono eseguite altre esecuzioni capitali, specialmente dopo la scomunica del 1570 e le conseguenti leggi di rappresaglia del 1571, che fece numerosissime vittime soprattutto tra i cosiddetti preti seminaristi. Il loro arrivo, infatti, segnò l'immediata ripresa della persecuzione.

Molti di essi erano stati educati in diversi Collegi all'estero: nel collegio di Douai (poi Reims) in Francia, fondato dal futuro cardinale Guglielmo Allen nel 1568, a Valladolid in Spagna, a Roma in Italia e a Vilna in Lituania, eretti appunto per la formazione dei giovani sacerdoti da inviare poi nella loro patria di origine. Tutti sapevano come il loro ritorno in Inghilterra equivaleva ad una sentenza di morte.

Questi collegi erano inoltre centri di informazione e di diffusione di notizie su ciò che accadeva in quelle terre. In essi si custodiva anche il ricordo di quanti, una volta partiti, erano stati arrestati e giustiziati in Inghilterra, Galles e Scozia. Qui si pregava davanti ai loro ritratti e si teneva viva, come anche in molti altri posti, la venerazione di questi martiri.

Ciò portò alla formulazione della teoria governativa che ogni prete inglese, ogni missionario era un traditore, e che tutti quelli che erano inviati da Roma erano spie, agitatori, cospiratori contro la vita della regina, fino a giungere alla proclamazione dell'editto del 23 novembre 1584 circa la sicurezza personale della regina. Nel gennaio del 1585 fu approvata una legge ancora più severa contro i cattolici, allo scopo di privarli di ogni assistenza spirituale e di ogni ministero sacerdotale. Infatti, la legge ordinava a tutti i sacerdoti di abbandonare entro un dato tempo 1'Inghilterra, proibiva ai giovani inglesi di diventare seminaristi nel continente, diffidandoli in caso contrario dal ritornare, pena la morte per alto tradimento. Infine, la legge estendeva la pena capitale a tutti coloro che li avessero ospitati ed avessero fornito loro vitto e alloggio.

L'ultimo editto di persecuzione emanato da Elisabetta il 2 novembre 1602 ordinò l'esilio di tutto il clero cattolico, pena la consueta sentenza di morte riservata ai traditori per chi fosse rimasto nel regno o vi fosse rientrato ed anche per chiunque avesse dato alloggio o aiuto a qualche sacerdote. Dopo la morte di Elisabetta e con l'avvento al trono di Jakob I Stuart (1603-1625), la situazione non mutò. Ai cattolici venne imposto, tra l'altro, il giuramento contro i poteri del papa e di assoluta fedeltà al re, che comportava l'immediata condanna contro chiunque si fosse rifiutato di prestarlo.

Vittima di queste leggi di repressione fu, fra altri, anche il gruppo degli 85 martiri qui elencati, composto da 63 sacerdoti, di cui 55 diocesani, 5 francescani, 2 gesuiti e 1 domenicano, e 22 laici. La maggior parte di essi fu condannata in base alla Legge Parlamentare del 1585, Legge contro Gesuiti, sacerdoti diocesani e persone similmente disobbedienti. In forza di questa legge, chiunque era stato ordinato sacerdote cattolico all'estero dopo il 24 giugno 1559 e penetrava nel Regno Unito o vi rimaneva era considerato colpevole di alto tradimento. Oltre a ciò, questa legge dichiarava reato ogni assistenza data a tali persone. Degli ottantacinque qui elencati ben settantacinque furono condannati in base a questa legge.

Non sorprende il fatto che in questo gruppo di martiri il numero dei sacerdoti sia così alto se si pensa che la legge del 1585 era primariamente diretta a sopprimere i sacerdoti cattolici. È da rilevare, che molti di questi sacerdoti condannati a morte erano di giovane età. Essi, sfidando i rigori della legge tornavano clandestinamente ma coraggiosamente nella loro patria, dopo essere stati formati nei collegi di Douai, Valladolid, Roma e Vilna, con l'unico scopo di diffondere il vangelo e di garantire la vita della Chiesa cattolica. Scoperti, furono giustiziati per la loro fedeltà alla chiesa di Cristo.

Il primo esempio di tale fermezza fu dato da Georg Haydock. Nato nel 1556 a Lancashire, studiò a Douai e Roma e fu ordinato sacerdote il 21 dicembre 1581. Al suo arrivo a Londra, il 6 febbraio 1582, venne subito arrestato e chiuso nella Torre ove per un anno e tre mesi visse nel buio e in piena solitudine. Messo poi sotto custodia normale, ebbe la possibilità di amministrare i sacramenti ai suoi compagni. Denunciato di nuovo insieme ad altri, il 2 febbraio 1584, venne impiccato. Quando lo tolsero dal patibolo era ancora vivo e perciò fu sventrato.

Insieme ai sacerdoti furono perseguitati anche i laici che davano loro ospitalità o che collaborarono con essi. Infatti, i 22 laici di questo gruppo di martiri sono stati condannati, perché erano stati sorpresi ad aiutare i sacerdoti o la Chiesa cattolica. Essi testimoniano per le migliaia di persone che misero a rischio la loro vita per sostenere e facilitare il compito di coloro che erano stati ordinati sacerdoti nei seminari allora funzionanti all'estero. Senza l'aiuto dei laici, i sacerdoti non avrebbero potuto vivere e operare in Gran Bretagna in quei tempi. Si deve inoltre ricordare che la maggior parte di questi sacerdoti proveniva da famiglie in cui la generosità verso i sacerdoti era grande.

Il primo di questo gruppo, che dovette pagare il suo lavoro con la vita, fu il tipografo William Carter. Nato a Londra nel 1548, tipografo e per anni segretario dell'ultimo Arcidiacono di Canterbury, Nicola Harpsfield, dopo la morte di questi fondò una tipografia. In essa stampò, tra altri libri cattolici, anche la nuova edizione di « Un trattato sullo scisma » di Gregory Martins, per cui nel 1580 venne messo in prigione e torturato. Infine il 10 gennaio 1584 fu impiccato e sventrato.

Fu soltanto in seguito alla restaurazione della Gerarchia Cattolica in Inghilterra e Galles, avvenuta nel 1850, che si poté affrontare efficacemente il lavoro per la Causa dei martiri di quei tempi nel Regno Unito. Cinquantaquattro di essi furono beatificati da Papa Leone XIII nel 1886, e altri nove nel 1895. Due di questi, John Fisher e Thomas More, furono poi canonizzati da Pio XI nel 1935.

Nel 1923 vennero svolte indagini e nel 1929 duecentotrentaquattro martiri vennero considerati, da parte del Promotore della Fede, come possibili candidati alla beatificazione.

Il 25 ottobre 1970, vennero canonizzati da Paolo VI quaranta dei predetti martiri, undici dei quali appartenevano al gruppo dei beati del 1886 e ventinove a quello del 1929. Nel corso della cerimonia di Canonizzazione Papa Paolo VI pronunciò questo messaggio: « Possa il sangue di questi Martiri sanare le profonde ferite che sono state inflitte alla Chiesa di Dio dalla separazione della Chiesa Anglicana dalla Chiesa Cattolica. None è forse una – ci chiedono questi Martini – la Chiesa fondata da Cristo? None è questa la loro testimonianza? ».

Mentre si svolgevano i lavori di preparazione per la canonizzazione dei Quaranta Martiri, il materiale storico e giuridico riguardanti gli altri non ancora beatificati veniva accuratamente riesaminato ed arricchito. Infine, all'inizio di ottobre 1978, si poté consegnare alla Congregazione per le Cause dei Santi il materiale riferentesi a ottantaquattro martiri. Ad esso si aggiunse in seguito, dietro richiesta della Gerarchia Scozzese, anche quello riguardante il Venerabile George Douglas.

[elenco in elaborazione]

Al termine di questo elenco di martiri ci si può

chiedere se in un'era contrassegnata da un autentico movimento verso la

riconciliazione e l'unità non sia opportuno considerare la Riforma come uno

scomodo episodio del passato che deve essere dimenticato. Dinanzi a tali

opinioni è doveroso ricordare che soltanto quando saremo capaci di guardare

oggettivamente gli eventi del passato, per quanto penosi essi possono essere,

saremo sinceri nella ricerca dell'unità. Così si legge nella dichiarazione

congiunta dell'Arcivescovo di Canterbury, Dr. Robert Runcie, e

dell'Arcivescovo di Westminster, Cardinale Basile Hume, diffusa in occasione

della beatificazione degli 85 martiri: « In occasione della beatificazione di

ottantacinque martiri d'Inghilterra, Scozia e Galles, ci uniamo per esprimere

la nostra gratitudine a Dio... La loro semplicità e l'eroica testimonianza data

della fede dei loro padri, insieme alla priorità che essi attribuivano a

Cristo e alla coscienza, possono essere di ispirazione anche per coloro i cui

padri spirituali avevano convinzioni cristiane diverse ».

Il 22 novembre 1987 Georg Haydock e ottantaquattro

compagni sono stati beatificati da Papa Giovanni Paolo II.

Autore: Andreas Resch

Fonte : I Beati di Johann Paolo II. Volume

II: 1986-1990