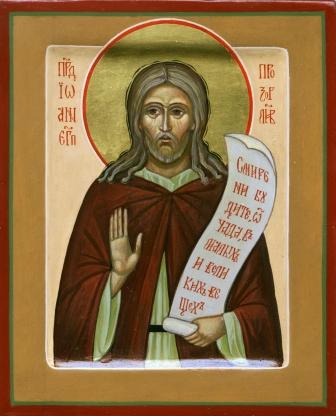

SAINT JEAN D'EGYPTE, ERMITE ET CONFESSEUR (+ 394)

I. VIE. - Jean d'Egypte, ou de Lycopolis, acquit une réputation de solitaire, presque égale à celle de saint Antoine (voir 17 janvier). Il naquit vers l'an 305, de parents peu connus dans le monde; il apprit dans son enfance le métier de charpentier et eut un frère teinturier. Parvenu à l'âge de 25 ans, il quitta le monde, se mit sous la conduite d'un ancien solitaire, et, jusqu'à la maturité de l'âge, il s'appliqua à lui rendre toutes sortes de services avec une humilité extraordinaire dont le bon vieillard lui-même était émerveillé. Ce maître voulut éprouver son disciple et s'assurer que l'obéissance provenait en lui d'une foi véritable et d'une profonde simplicité. Un jour, il ramassa, dans son bûcher, une branche d'arbre coupée depuis longtemps; il l'enfonça en terre et dit à Jean de l'arroser deux fois le jour pour lui faire reprendre vie. Le jeune homme reçut cet ordre avec respect et soumission, puis se mit en devoir de l'exécuter : tous les jours, il allait chercher de l'eau à une distance de deux milles, sans que rien pût le distraire de ce travail. Au bout d'un an, le vieillard eut compassion de la peine qu'il se donnait. "Jean", lui dit-il, "cette branche a-t-elle pris racine?" Le disciple répondit qu'il n'en savait rien. Le maître tira la branche, comme pour voir si elle tenait au sol; il l'arracha sans aucun effort, la rejeta et dit au disciple de ne plus l'arroser.

Quelques visiteurs solitaires du voisinage étaient venus s'édifier auprès du vieillard : celui-ci appela son disciple Jean et lui ordonna d'aller jeter par la fenêtre une fiole d'huile, la seule qui pût pourvoir aux nécessités des solitaires et de leurs hôtes. Jean exécuta l'ordre aussitôt, sans se préoccuper du besoin que l'on pouvait avoir de cette huile. Dans une autre circonstance, le maître lui dit : "Jean, allez vite et roulez promptement cette pierre que vous voyez." Or il s'agissait d'un véritable rocher que plusieurs personnes n'auraient même pas pu ébranler. Le disciple courut aussitôt, poussa la pierre, fit de grands efforts pour la remuer à tel point que la sueur coulait sur ses habits et jusque sur la pierre elle-même. Ce furent là, dit Cassien, des traits d'obéissance qui valurent plus tard à ce Jean, ermite, le don de prophétie.

Lorsque le vieillard vint à mourir, Jean, qui pouvait avoir 37 ans, passa environ 5 ans encore dans divers monastères. Il se retira ensuite sur une montagne à quelques milles de Lycopolis : là, il construisit lui-même trois pièces voûtées, la première pour la toilette et les nécessités du corps, la seconde pour le travail et les repas, la troisième pour la prière. Il ferma l'entrée avec soin; personne ne pouvait pénétrer dans le lieu de sa retraite et lui-même n'en sortait jamais; il avait seulement une fenêtre par laquelle on lui passait ce qui lui était nécessaire, et par laquelle aussi il s'entretenait avec ceux qui venaient le consulter. Il vécut ainsi durant 48 ans, sans sortir de sa cellule, sans voir une seule femme, sans toucher une seule pièce de monnaie, sans que personne l'eût jamais vu ni manger ni boire.

Toujours seul avec Dieu dans cette solitude, l'ermite s'entretenait avec le Seigneur, la nuit et le jour, lui adressait ses prières et ses supplications. Lorsque quelques personnes lui rendaient visite, il voulait qu'on s'acquittât à leur égard de tous les devoirs de l'hospitalité. Lui-même ne mangeait que le soir et se contentait de quelques fruits. Le démon le tourmenta de diverses façons; une fois, il lui suggéra l'idée de jeûner deux jours de suite pour occasionner l'affaiblissement de son corps et un surcroît de fatigue nullement nécessaire; il troublait sa prière et son repos, remplissait son imagination de divers fantômes.

Vers l'an 375 se manifesta en Jean d'Égypte le don de prophétie dont Cassien nous a parlé aux personnes qui venaient du voisinage ou des pays éloignés, Jean faisait connaître ce qu'elles avaient de plus caché au fond du coeur; quand elles avaient commis quelque péché en secret, il les en reprenait sévèrement en particulier, les exhortait à s'en corriger et à en faire pénitence. Il annonçait par avance ce que seraient les débordements du Nil, grands ou médiocres. Il prédit en particulier la défaite des Ethiopiens qui étaient entrés sur les terres de l'empire dans la Haute-Thébaïde. Le général qui commandait les troupes romaines était venu le trouver pour lui exprimer ses craintes : "Allez en toute confiance", répondit le solitaire, "vous serez victorieux des ennemis, vous vous enrichirez de leurs dépouilles, et reprendrez sur eux tout ce qu'ils ont emporté."

Et il ajouta "Vous serez comblé d'affections par l'empereur". L'effet réalisa toutes ces promesses.

Une servante de Dieu, du nom de Poemenia, s'était approchée pour le voir : il ne voulut pas l'entretenir, mais se contenta de lui faire connaître un certain nombre de choses secrètes. Il l'engagea à ne pas faire un détour pour passer dans Alexandrie, quand elle descendrait de la Thébaïde, car des épreuves l'attendaient dans cette ville. Soit oubli, soit calcul, Poemenia se dirigea vers la cité : en chemin elle fit arrêter son bateau à Niciopolis sur le Nil. Les serviteurs, descendus à terre, se prirent de querelle avec les gens de l'endroit; les indigènes tuèrent l'un de ses eunuques, coupèrent le doigt à un autre, jetèrent dans le fleuve un saint évêque nommé Denis qui se trouvait sans doute sur le bateau, blessèrent les autres serviteurs et accablèrent d'injures et de menaces Poeménie elle-même.

Ces diverses prédictions réalisées firent connaître Jean jusqu'à la cour de l'empereur Théodose : le prince se voyant attaqué par Maxime qui disposait de forces supérieures aux siennes, envoya consulter le serviteur de Dieu aux extrémités de la solitude. Jean fit répondre à Théodose qu'il remporterait la victoire sans répandre beaucoup de sang et qu'il retournerait triomphant dans les Gaules; il lui donnait en même temps de bonnes nouvelles concernant le tyran Eugène.

Le saint solitaire reçut aussi le don de guérir les maladies; mais pour éviter dans ces oeuvres extraordinaires, toute apparence de vanité, il ne permettait pas qu'on lui amenât les malades, il se contentait de leur envoyer de l'huile qu'il avait bénite

Aussitôt que les patients se servaient de cette huile, ils étaient guéris de leurs infirmités. La femme d'un sénateur, étant devenue aveugle, conjura son mari de la conduire à l'homme de Dieu. Quand elle fut arrivée, Jean lui fit savoir qu'il ne voyait jamais de femmes. Elle le pria du moins de lui faire connaître quelle était la cause de son mal et de demander à Dieu sa guérison. Le sénateur se présenta avec cette requête, l'ermite se mit aussitôt en prière, bénit de l'huile qu'il fit porter à la dame. Pendant trois jours, celle-ci mit de l'huile sur ses yeux : alors elle recouvra la vue et rendit grâces à Dieu.

Un maître de camp, chargé de conduire des soldats à Syène, menait sa femme avec lui il vint trouver l'ermite sur sa montagne, le conjura d'exaucer le désir de sa femme qui désirait extrêmement recevoir sa bénédiction. "C'est impossible", répondit Jean, "depuis 40 ans que je me suis enfermé sous ce rocher, je n'ai pont vu visage de femme." Attristé de cette réponse, le maître de camp va trouver son épouse et lui rend compte de l'insuccès de sa démarche. La femme insiste, proteste avec serment qu'elle ne partira pas sans avoir vu le prophète. Le mari revient vers Jean, lui affirme que son épouse mourra sans doute de chagrin et que cette mort lui sera imputable : il renouvelle ses instances et ses prières, si bien que l'ermite finit par lui dire : "Allez, votre femme me verra cette nuit pendant son sommeil sans venir ici et sans sortir de sa maison." L'officier se retira, repassant dans son esprit cette réponse ambigué; il la rapporta à son épouse, qui en conçut une peine très vive. La nuit suivante, l'homme de Dieu lui apparut en songe et lui dit : "O femme, votre foi est grande, elle m'oblige à venir ici pour satisfaire votre demande. Je vous avertis néanmoins que vous ne devez pas désirer voir le visage mortel et terrestre des serviteurs de Dieu, mais plutôt contempler des yeux de l'esprit leur vie et leurs actions. Car la chair ne profite à rien, c'est l'esprit qui vivifie. Et après tout, pourquoi avez-vous tant désiré de me voir? Suis-je un prophète plus juste et plus saint que les autres? Je suis un homme sujet comme vous au péché et aux autres infirmités humaines. Ainsi ce n'est point en qualité de prophète ni de juste, mais seulement à cause de votre foi que j'ai eu recours à l'assistance de Notre-Seigneur; il vous accorde la guérison de toutes les maladies que vous endurez dans votre corps. A dater de ce jour, vous jouirez donc, vous et votre mari, d'une parfaite santé, votre maison sera toute remplie des bénédictions du ciel. Mais n'oubliez jamais tous deux ces bienfaits que vous recevrez de Dieu; vivez toujours dans sa crainte et ne demandez rien au delà des appointements qui sont dus à votre fonction. Contentez-vous aussi de m'avoir vu en songe et n'exigez pas davantage." A quoi il ajouta tous les avis utiles à une femme chrétienne et disparut. A son réveil, la femme rapporta à son mari ce qu'elle avait vu; par la description qu'elle fit du saint homme, il ne douta point de la réalité du fait, retourna à la grotte pour remercier Jean et continua son voyage. Saint Augustin qui rapporte cette histoire (Procura de mortuis, c.17), ajoute qu'il la tenait d'une personne digne de confiance.

Palladius, dans son "histoire lausiaque", a raconté ainsi la visite qu'il rendit au solitaire avec plusieurs autres, et il a retracé les admirables instructions qu'ils reçurent de sa bouche. « Avec ceux qui entouraient le bienheureux Evagre, nous cherchions à apprendre avec précision quelle était la vertu de cet homme. Alors Évagre dit « J'apprendrais volontiers de celui qui sait apprécier intelligence et discours, de quelle catégorie est l'homme. Car s'il arrive que je ne puisse le voir moi-même, mais que je puisse entendre exactement un autre s'exprimer sur sa manière de vivre, je n'irai pas jusqu'à sa montagne." Pour moi, continue Pallade, ayant entendu, et n'ayant rien dit à personne, je demeurai un jour en repos; le lendemain je fermai ma cellule, je la confiai elle et moi-même à Dieu et je partis pour la Thébaïde. [Il était alors au désert de Nitrie.] J'arrivai au bout de huit jours, après avoir voyagé tantôt à pied, tantôt en bateau sur le fleuve. C'était le temps de la crue, à une époque où beaucoup tombent malades, j'eus moi-même à souffrir. Étant donc arrivé, je trouvai le vestibule fermé. Ce vestibule où tiennent environ 100 personnes, les frères le fermaient à clef et l'ouvraient seulement le samedi et le dimanche. Je restai tranquille jusqu'au samedi à la 2ième heure, je me présentai pour l'entrevue, Jean était assis à la fenêtre par laquelle il adressait ses consolations à ceux qui s'approchaient. Il me salua et me dit par un interprète : "D'où es-tu, et pourquoi es-tu venu? Je conjecture que tu es du couvent d'Évagre." A quoi je dis : "Je suis étranger, issu de Galatie; mais je suis dans l'intimité d'Evagre." Pendant que nous parlions, survint le gouverneur de la contrée nommé Alypius. Jean se tourna vers lui et interrompit son entretien avec moi. Alors je me retirai en arrière pour faire place au gouverneur. Ils conversèrent longtemps, je me décourageai et murmurai contre le beau vieillard qui m'avait dédaigné. Je songeais à me retirer, quand appelant son interprète, nommé Théodore, Jean lui dit : "Va dire à ce frère : "N'aie pas d'étroitesse d'âme; dans un moment je vais congédier le gouverneur et t'entretenir." - Alors, je vis en lui un homme inspiré et je m'appliquai à patienter encore. Lorsque le gouverneur fut parti, Jean me rappela et me dit : "Pourquoi as-tu été froissé à mon sujet? Qu'as-lu trouvé qui fût digne de blâme? Tu as eu des pensées qui ne s'appliquent pas à moi et qui ne te conviennent pas. Ne sais-tu pas qu'il est écrit "N'ont pas besoin de médecin ceux qui sont en santé, mais bien ceux qui éprouvent des malaises (Luc., 5, 31). Je te trouve quand je veux et il en est de même pour toi. Et s'il arrive que je ne te console pas moi-même, d'autres frères et d'autres pères sont là pour te consoler. Mais celui-ci est comme livré au diable par ses affaires mondaines; il est venu ici pour recevoir de l'aide, pour respirer un moment comme un esclave qui se dérobe à son maître. C'eût été bien étrange de le laisser pour s'occuper de toi qui as du loisir pour traiter de ton salut. "

Je lui demandai de prier pour moi et je fus convaincu qu'il était inspiré de Dieu, il me caressa de la main et me dit : "Beaucoup d'afflictions t'attendent, et tu as été en butte à bien des hostilités pour sortir du désert. Tu t'es montré timide et tu as différé. Le démon sous de pieux prétextes te relance. Il t'a suggéré en effet de regretter ton père, puis d'instruire ton père et ta soeur en vue de la vie monastique. Eh bien! voici que je t'annonce une bonne nouvelle : tous deux sont sauvés, car ils ont renoncé au monde. Quant à ton père, en ce moment même, il a d'autres années à vivre. Par conséquent, demeure fermement dans le désert, ne cherche pas à retourner dans ton pays à cause d'eux. Car il est écrit "Personne ayant mis la main à la charrue, et retournant en arrière, n'est apte au royaume des cieux" (Luc, 9, 62)". Suffisamment raffermi par ces paroles, je rendis grâces à Dieu en apprenant que mes inquiétudes allaient prendre fin.

Jean me dit encore : "Veux-tu devenir évêque?" -- "Mais je le suis", répondis-je. « Et où donc?" "Aux cuisines, aux caves, aux tables, à la vaisselle. J'exerce la surveillance tel est mon épiscopat, c'est la gourmandise qui m'a préposé." Il me dit avec un sourire : "Trêve de plaisanterie, il te faut être ordonné évêque, tu auras à peiner, à souffrir. Par conséquent si tu fuis les afflictions, ne sors pas du désert, là personne ne peut t'ordonner évêque. "

Je me séparai de lui et m'en allai dans mon désert habituel; je racontai les détails de cet entretien aux Pères qui deux mois plus tard allèrent le trouver. Pour moi, j'oubliai ses paroles; au bout de trois ans, je tombai malade, d'une infirmité d'estomac. Je fus envoyé par les frères à Alexandrie, et j'y soignai une hydropisie. D'Alexandrie sur le conseil des médecins, je passai en Palestine où l'air est plus léger. De Palestine je gagnai la Bithynie, et là je ne sais pour quelle cause, je fus jugé digne de l'ordination. "

Ce qu'Évagre et Pétrone rapportèrent de leur visite au bienheureux Jean, Pallade ne l'a pas inséré dans son Histoire lausiaque. Rufin, dans son "Histoire des moines" (P. L., t. 21, col. 391) a suppléé à ce silence : il a raconté comment Jean entretint, pendant trois jours, Pétrone et ceux qui l'accompagnaient. A la fin, le solitaire leur donna sa bénédiction "Allez en paix, mes enfants, leur dit-il, sachez que les nouvelles de la victoire remportée par Théodose sur le tyran Eugène sont arrivées aujourd'hui à Alexandrie; mais cet excellent empereur terminera bientôt sa vie par une mort naturelle."

Quand nous eûmes quitté Jean, dit Pétrone, nous sûmes que les événements, prédits par lui, étaient arrivés. Quelques jours plus tard, des frères vinrent nous apprendre que le grand serviteur de Dieu s'était reposé en paix (fin 394). On rapporte qu'il ne permit à personne de lui parler pendant trois jours; ce court intervalle écoulé, il se mit à genoux, commença son oraison et s'en alla jouir de la présence de Dieu.

II. CULTE. -- La mort de Jean est placée par les uns au 20 septembre, par les autres au 17 octobre 394. Il paraît d'ailleurs certain qu'elle arriva avant celle de Théodose survenue à Milan le 17 janvier 395. Par conséquent, le 27 mars, marqué dans les martyrologes latins depuis le 9ième siècle, ne peut avoir été le "dies natalis".

On s'étonne que les grecs n'aient pas fait mention de lui dans leurs ménologes. Jean avait cependant une réputation de sainteté répandue par tout l'empire : on l'appelait le prophète d'Egypte, le prophète particulier de l'empereur Théodose. Baronius a cru, mais à tort, que les grecs en parlaient à la date du 13 décembre. Les Égyptiens et les Coptes honoraient la mémoire de Jean un jour d'automne correspondant au 17 octobre. Sa fête est célébrée en Portugal, peut-être par suite de la dévotion ou de saint Martin de Dume, ou de saint Fructueux.

Bibl. - Les renseignements sur ce saint peuvent être puisés dans Pallade, "Histoire lausiaque", c. 35 (trad. Lucot); dom Rufin, "Historia monachorum", t. 1, ou "Vitae Patrum", édit. Rosweyde; P. L., t. 21, col. 39t; dans J. Cassien, Institut., col. 23-26 et Collationes, 1. I, c. 21; 1. 24, c.26. - Acta sanctorum, 27 mars. - Tillemont, Mémoires pour servir à l'hist. ecclés., t. 9, p. 9, etc.

in : Sanctoral des R.P. Bénédictins de Paris, éd. Letouzey & Ané 1936, volume "mars"

http://www.amdg.be - retranscription du texte des "Petits Bollandistes", 7ième édition, Bar-le-Duc 1876

JEAN naquit à Lycopolis, en Basse-Thébaïde, l'an 305, de parents pauvres, mais chrétiens. Ce n'est qu'après avoir exercé jusqu'à vingt-cinq ans le métier de charpentier que, touché de la grâce divine et considérant que la grande affaire de la vie est de sauver son âme, il quitta tout pour DIEU.

Il alla se mettre d'abord sous la direction d'un ancien solitaire, qui l'exerça d'une manière vraiment extraordinaire à l'obéissance, et qui lui commandait même des choses en apparence déraisonnables, afin de l'habituer à obéir uniquement pour plaire à DIEU.

C'est ainsi qu'il lui ordonna d'arroser deux fois le jour, pendant un an, un bâton sec et à demi pourri, jusqu'à ce qu'il eût pris racine et porté des fruits ; il fallait aller chercher l'eau à deux milles de distance, sous le brûlant soleil d'Egypte. Un jour, il ne leur restait qu'une fiole d'huile pour assaisonner leurs légumes ; Jean reçut l'ordre de la jeter par la fenêtre, ce qu'il exécuta sans la moindre objection.

Le vieux solitaire lui dit une autre fois : "Vois-tu cet énorme rocher? Apporte-le ici. » Le disciple part et s'efforce de saisir et de rouler ce bloc ; son corps, inondé de sueur, s'épuise ; Jean ne cesse son travail infructueux que sur l'appel de son maître.

Une telle obéissance laisse à deviner quelle était la sainteté du jeune ermite. Après douze ans de cet exercice de complète abnégation, Jean passa plusieurs années en différents monastères, pour se former mieux encore aux vertus religieuses; et ce n'est qu'après ces longues épreuves que, cédant à l'attrait qui le poussait dans la solitude, il obtint la permission de se cacher, loin des hommes, dans une retraite absolue.

Il se creusa dans le rocher une grotte inaccessible, où il ne laissa pour ouverture qu'une petite lucarne par où lui parvenait sa nourriture. La bonne odeur de sa sainteté attira bientôt les foules à son désert, et, craignant que la charité ne lui fît un devoir de ne point les rebuter, il régla qu'il leur parlerait par sa fenêtre, mais seulement le samedi et le dimanche.

Il est incroyable combien il fit de prédictions et de miracles et combien d'âmes lui durent leur conversion ou leur sanctification. Sa vie était toute céleste ; son jeûne continuel ne lui permettait chaque jour de prendre que quelques fruits et un peu d'eau ; il ne mangeait jamais rien de cuit, pas même de pain; le même vêtement lui suffisait pour le garantir des ardeurs du jour et des fraîcheurs de la nuit.

C'est ainsi qu'il vécut cinquante ans, sans aucun souci des choses de ce monde, et tout occupé de DIEU et des choses éternelles. Il rendit enfin sa belle âme au SEIGNEUR, à genoux et en prière, à la fin de l'an 394, laissant la réputation d'un digne émule de Saint Antoine.

Pratique. Ne sortez jamais de la voie de l'obéissance ; cette vertu vous préservera des illusions et de l'orgueil.

XXXV – JEAN DE

LYCOPOLIS

[1] Il y eut un certain Jean dans la ville de Lyco,

qui dans son enfance apprit le métier de charpentier; il avait un frère

teinturier. Puis plus tard, arrivé à vingt-cinq ans environ, il renonça au

monde. Et avant passé cinq ans dans différents monastères, il se retira seul

sur la montagne de Lyco, s'étant fait sur le sommet lui-même trois chambres

voûtées, et, y étant entré, il s'emmura. Or une des voûtes était pour les

besoins de la chair, une où il travaillait et mangeait, et l'autre où il

faisait ses prières. [2] Ayant passé trente années complètes enfermé et

recevant par une fenêtre de celui qui l'assistait les choses nécessaires, il

fut jugé digne du don de prédictions. Entre autres même il envoya différentes

prédictions au bienheureux empereur Théodose, et, à propos du tyran Maxime,

qu'après l'avoir vaincu, il s'en reviendra des Gaules. Et pareillement encore

il lui donna de bonnes nouvelles au sujet du tyran Eugène. Un renom

considérable se répandit relativement à sa vertu.

[3] Or pendant que nous étions dans le désert de

Xitrie, moi et ceux qui entouraient le bienheureux Evagre, nous cherchions à

apprendre avec précision quelle était la vertu de cet homme. Alors le

bienheureux Evagre dit : « J'apprendrais volontiers de celui qui sait apprécier

intelligence et discours, de quelle catégorie est l'homme. Car s'il arrive que

moi-même je ne puisse le voir, mais que je puisse entendre exactement un autre

raconter ce qui concerne sa manière de vivre, je ne vais pas jusqu'à sa

montagne. Pour moi, ayant entendu et n'ayant rien dit à personne, je demeurai

un jour en repos, et, le lendemain, ayant fermé ma cellule et ayant confié à

Dieu moi-même avec elle, je me surmenai de hâte jusqu'en Thébaïde. [4] Et

j'arrivai au bout de dix-huit jours, tantôt à pied, tantôt en bateau sur le

fleuve. Mais c'était le temps de la crue, durant lequel beaucoup tombent

malades, et certes c'est ce que moi aussi j'eus à supporter. Etant donc parti,

je trouvai le vestibule de celui-là fermé. Car plus tard, les frères bâtirent à

côté un vestibule très grand où tiennent environ cent personnes. Et, le fermant

à clef, ils l'ouvraient le samedi et le dimanche. Par conséquent ayant appris

la cause pour laquelle il avait été fermé, je restai tranquille jusqu'au

samedi.

Et m’étant présenté à la deuxième heure pour

l'entrevue, je le trouvai assis à la fenêtre, au travers de laquelle il paraissait

consoler ceux qui s'en approchaient. [5] M'ayant donc salué, il me disait par

interprète : « D'où es-tu, et pourquoi es-tu venu? Car je conjecture que tu es

du couvent d'Evagre. » Je dis ceci : « Etranger, issu de Galatie. » Et j'avouai

que j'étais dans l'intimité d'Evagre. Pendant que nous parlions, survint le

gouverneur de la contrée, du nom d'Alypius. S'étant empressé vers lui, il

abandonna la conversation avec moi. Alors m'étant retiré un peu, je leur donnai

de la place en me tenant de loin. Mais eux conversant pendant longtemps, je nie

décourageai et, étant découragé, je murmure contre le beau vieillard, de ce

qu'il m'avait méprisé et qu'il avait honoré celui-là. [6] Et dégoûté à cause de

cela, j'envisageais la pensée de me retirer en l’ayant méprisé. Mais ayant

appelé son interprète, nommé Théodore, il lui dit : « Va, dis à ce frère :

N'aie pas de petitesse d'âme. Tout à l'heure je congédie le gouverneur, et je

te parle. » Alors je crus en lui comme en un inspiré et je m'appliquai à

patienter encore. Et le gouverneur étant sorti, il me rappelle et me dit : «

Pourquoi as-tu été blessé au sujet de moi? Qu'as-tu trouvé digne de blâme,

puisque tu as pensé des choses qui ne s'appliquent pas à moi et qui ne te

siéent pas? Ou bien ne sais-tu pas qu'il est écrit : « N'ont pas besoin de

médecin ceux qui sont en santé, mais ceux qui éprouvent des malaises »(Luc, 5,

31)? Je te trouve quand je veux, et toi moi. [7] Et s'il arrive que moi je ne

te console pas, d'autres frères ainsi que d'autres pères te consolent. Mais

celui-ci est livré au diable par ses affaires mondaines, et, parce qu’il a

respiré durant une heure bien courte, comme un esclave qui a fui son maître, il

est venu pour recevoir de l'aide. Il eût donc été étrange que nous l'ayons

laissé pour nous occuper de toi, alors que tu as du loisir continuellement pour

ton salut. » Cela étant, l'ayant supplié de prier pour moi, je fus convaincu

que c'était un homme inspiré. [8] Alors faisant le gracieux, ayant souffleté

doucement de sa main droite ma joue gauche, il me dit : « Beaucoup

d'afflictions t'attendent et tu as été en butte à des hostilités beaucoup pour

sortir du désert. Et tu t'es montré timide et tu as différé. Mais le démon

t'apportant des prétextes pieux et rationnels te relance. Il t'a suggéré en

effet de regretter ton père et de catéchiser ton père et ta sœur en vue de la

vie monastique. [9] Eh bien, voici que je t'annonce une bonne nouvelle : tous

deux ont été sauvés, car ils ont renoncé au monde. Quant à ton père, en ce

moment même, il a d'autres années à vivre. Par conséquent, tiens ferme dans le

désert, et, à cause d'eux, ne veuille pas t'en aller dans ta patrie. Il est

écrit en effet : « Personne ayant mis la main à la charrue et s'étant retourné

en arrière n'est apte au royaume des cieux » Luc, 9, 62 . Alors ayant tiré

profit de ces paroles et étant suffisamment raffermi, je rendis grâces à Dieu,

ayant appris que les prétextes qui me pressaient étaient à leur fin.

[10] Ensuite il me dit de nouveau en faisant le

gracieux : « Veux-tu devenir évêque? » Je lui dis ceci : « Je le suis. »

Et il me dit : « Où? » Je lui dis : « Aux cuisines, aux caves, aux tables, aux

vaisselles; je fais l'évêque là-dessus, et s'il arrive qu'il y ait du petit vin

qui aigrisse, je le mets à part, mais je bois le bon. Pareillement, je suis

aussi l'évêque de la marmite, et s'il manque du sel ou un des assaisonnements,

je l'y mets et assaisonne, et alors je la mange. Tel est mon épiscopat : car

c'est la gourmandise qui ma ordonné. » [11] Il me dit avec un sourire : «

Quitte les plaisanteries. Tu as à être ordonné évêque. à peiner beaucoup et à

être affligé. Par conséquent, si tu fuis les afflictions, ne sors pas du

désert, car dans le désert personne ne peut t'ordonner évêque. »

M'étant

alors séparé de lui, je m'en allai au désert dans mon endroit habituel, et je

racontai ces choses mêmes aux bienheureux pères, lesquels, après deux mois,

ayant navigué s'en allèrent et le rencontrèrent. Or moi j'oubliai ses paroles.

Car après trois ans. je tombai malade d'une infirmité de rate et d'estomac.

[12] De là je fus envoyé à Alexandrie par les frères et j'y soignai une

hydropisie. D'Alexandrie, les médecins, à cause de l'air, me conseillèrent de

me rendre dans la Palestine; car elle a de l'air léger en rapport avec notre

tempérament. De Palestine je gagnai la Bithynie, et là, —je ne sais comment,

soit par empressement des humains, soit par la bonne volonté du Plus-Puissant,

Dieu le saurait, — je fus jugé digne de l'ordination sur moi : je m'étais mêlé

aux conjonctures relatives au bienheureux Jean. [13] Et pendant onze mois,

caché dans une cellule ténébreuse, je me souvins de cet (autre) bienheureux,

parce qu'il m'avait prédit ce que j'ai subi. Et pourtant, à dessein de m'amener

par son récit à la patience du désert, il me racontait ceci en ces termes : «

J'ai quarante-huit ans de cette cellule ; je n'ai pas vu de visage de femme,

pas d'image de monnaie; je n'ai pas vu quelqu'un en train de mâcher et

quelqu'un ne m'a pas vu manger ni boire. »

[14] La servante de Dieu, Poeménie, s'étant approchée

pour le voir, il ne se rencontra pas même avec elle ; mais il lui fit savoir

aussi un certain nombre de choses secrètes. Puis il l'engagea à ne pas se

détourner sur Alexandrie en descendant de la Thébaïde; « car autrement tu as à

tomber sur des épreuves ». Mais elle, ayant calculé différemment ou bien ayant

oublié, se dirigea sur Alexandrie pour voir la ville. Or pendant la route, ses

embarcations abordèrent près de Niciopolis pour relâcher. [15] Cela étant, ses

serviteurs étant sortis engagèrent, par suite d'un certain désaccord, une lutte

avec les indigènes, gens furieux. Ceux-ci enlevèrent le doigt d'un eunuque, en

tuèrent un autre, et n'ayant pas reconnu le très saint évêque Denys, ils le

plongèrent même dans le fleuve, et elle, ils l'accablèrent d'injures et de

menaces, après avoir blessé tous les autres serviteurs.

HISTOIRE LAUSIAQUE (Vies d'ascètes et de Pères du désert). Textes et Documents pour l'étude historique du christianisme publiés sous la direction de Hlppolyte HEMMER et Paul LEJAY. Texte grec, introduction et traduction française par A. LUCOT, aumônier des Chartreux à Dijon, Paris, Librairie Alphonse Picard et Fils, 82, rue Bonaparte, 82, 1912

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/saints/palladius/palladius.htm#_Toc199164327St. John of Egypt

St. John of Egypt was born in Lycopolis, modern Assiut, Egypt, and spent his youth as a carpenter under his father. Then feeling a call from God, he left the world and committed himself to a holy solitary in the desert. He was a man who desired to be alone with God and became one of the most famous hermits of his time.

For ten years he was the disciple of an elderly, seasoned hermit. This holy man taught him how to be holy. St. John called him his “spiritual father.” After the older monk’s death, St. John spent four or five years in various monasteries because he wanted to know how monks pray and live.

Finally, John found a cave high in the rocks. The area was quiet and protected from the desert sun and winds. He divided the cave into three parts: a living room, a work room and a little chapel. He then walled himself up with a single window opening to preach to the people who came to see him and seek his advice about important matters. Even Emperor Theodosius I asked his advice twice.

People in the area brought him food and other necessities. When so many people came to visit him, some men became his disciples. They stayed in the area and built a hospice. They took care of the hospice so that more people could come to benefit from the wisdom of this hermit.

Such well-known saints as Augustine and Jerome wrote about the holiness of St. John. St. John was able to prophesy future events. He could look into the souls of those who came to him. He could read their thoughts. When he applied blessed oil on those who had a physical illness, they were often cured.

Even when John became famous, he remained humble and did not lead an easy life. He never ate before sunset. When he did eat, his food was dried fruit and vegetables. He never ate meat or cooked or warm food. St. John knew that his life of self-sacrifice would help him stay close to God. He died peacefully in 394 at the age of ninety. The three last days of his life John gave wholly to God: on the third he was found on his knees as if in prayer, but his soul was with the blessed.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-john-of-egypt/

John of Egypt (RM)

(also known as John of Lycopolis)

Born at Asyut (Assiut or Lycopolis), Egypt, c. 304; died near there in 394 or 395; feast is October 17 in the Coptic Church. John was a carpenter (or shoemaker) at Asyut who at 25 became a hermit on a neighboring mountain for the next 40 years. To test his humility and obedience the ancient anchorite who resided there made John perform seemingly ridiculous acts, such as water a dry stick for a whole year, all of which he executed with the utmost fidelity. He seems to have lived with the old hermit for the 12 years until the holy man's death, then spent four years in various monasteries.

When he was about 40, John walled himself into a cell on the top of a rock near Asyut, where he never ate until after sunset, and then very sparingly. Weekdays he spent his time in prayer. On Saturdays and Sundays, he spoke through the little window in his cell to the many men who came to him for instruction and spiritual advice. He allowed a type of hospital to be built near his cell, where some of his disciples took care of his visitors. These men were drawn by his reputation for miracles of healing, gift of prophecy, and ability to read souls.

Saint John's gift for foretelling the future was such that he was given the surname `Prophet of the Thebaid.' When Emperor Theodosius the Elder was attacked by the tyrant Maximus, who had killed Emperor Gratian in 383 and dethroned Valentinian in 387, he consulted John about the proposed war against Maximus. John foretold that Theodosius would be victorious, almost without blood. The emperor, full of confidence, marched into the West, defeated the more numerous armies of Maximus twice in Pannonia; crossed the Alps, took the tyrant in Aquileia. He returned triumphant to Constantinople, and attributed his victories to the prayers of Saint John, who also foretold him the events of his other wars, the incursions of barbarians, and all that was to befall his empire.

In 392, Eugenius, by the assistance of Arbogastes, who had murdered the emperor Valentinian the Younger, usurped the empire of the West. Theodosius instructed Eutropins the Eunuch to try to bring John to Constantinople; if he would not come, Eutropins was to consult with the saint whether it was God's will that he should march against Eugenius, or wait his arrival in the East. John would not leave his cell but predicted the emperor's success, but this time many lives would be lost and Theodosius would die in Italy. Theodosius marched against Eugenius, and lost 10,000 men in the first engagement. He was almost defeated: but renewing the battle on the next day, September 6, 394, he was entirely victorious by the miraculous interposition of heaven, as even the heathen poet Claudian acknowledges. Theodosius died in the West, January 17, 395, leaving his two sons emperors (Arcadius in the East, and Honorius in the West).

Among Saint John's reported miracles was the restoration of sight to the wife of a senator through the vehicle of oil he blessed. It had to be through such a medium with women, for he refused to speak with any woman. One interesting incident is related by Evagrius, Palladius, and Augustine in his treatise of On the Care for the Dead. One of the emperor's officers begged John to allow his wife to speak to him. She had made the difficult and dangerous journey to Lycopolis for that purpose. The holy man answered, that during his stricter enclosure for the last forty years, he had imposed on himself an inviolable rule not to see or converse with women; so he desired to be excused the granting her request. The officer returned to his virtuous, but disappointed, wife, who begged her husband to try again.

Returning to John, the husband said that his wife would die of grief if he refused her request. The saint said to him: "Go to your wife, and tell her that she shall see me tonight, without coming hither or stirring out of her house." When she was asleep that night, the man of God appeared to her in her dream, and said: "Your great faith, woman, obliged me to come to visit you; but I must admonish you to curb the like desires of seeing God's servants on earth. Contemplate only their life, and imitate their actions. As for me, why did you desire to see me? Am I a saint or a prophet like God's true servants? I am a sinful and weak man. It is, therefore, only in virtue of your faith that I have had recourse to our Lord who grants you the cure of the corporal diseases with which you are afflicted. Live always in the fear of God, and never forget his benefits." He added several proper instructions for her conduct, and disappeared.

Upon awakening the woman described to her husband the person she had seen in her dream and he confirmed that it was John. Whereupon he returned the next day to thank him. But when he arrived, the saint would not permit it. The officer received his benediction, and continued his journey to Seyne.

In 394, Palladius, who later became bishop of Helenopolis and one of the authors of John's vita, visited the saint in July. When he arrived, he found that he would have to wait until Saturday to speak with John. He returned that day in the early morning, saw the saint sitting at his window talking with others. Through an interpreter, introductions were made and Palladius was identified as a member of Evagrius's community.

Their conversation was interrupted by the hasty arrival of Alypius, governor of the province, in great haste. John asked Palladius to step aside for the governor with whom the saint engaged in a long discussion while an increasingly impatient Palladius had to wait. The weary man began to complain internally that the saint was showing preference to rank. He was about to leave when John sent his interpreter to stop him saying, "Go, bid that brother not to be impatient: I am going to dismiss the governor, and then will speak to him."

Palladius, astonished that his thoughts should be known to him, waited patiently. When Alypius had left, John called Palladius, and asked: "Why were you angry, unjustly imputing guilt to me in your mind? To you I can speak at any other time, and you have many fathers and brethren to comfort and direct you in the paths of salvation. But this governor, being involved in the hurry of temporal affairs, and having come to receive some wholesome advice during the short time his affairs will allow him time to breathe in, how could I give you the preference?"

He then told Palladius what passed in his heart: his secret temptations to quit his solitude. He told Palladius that it was the devil who tempted him with images of his father's loneliness at his absence, and that he might induce his brother and sister to embrace a solitary life. The holy man told him to ignore such suggestions, because his siblings had already renounced the world, and his father would live seven more years. He foretold him that he should meet with great persecutions and sufferings, and should be a bishop, but with many afflictions: all which came to pass, though at that time extremely improbable. The text of Palladius's account of their meeting still exists.

That same year John was visited by Saint Petronius with six other monks. The hermit asked if any of them was in holy orders and they answered, "no." In fact, Petronius was a deacon but had not disclosed this to his fellow travellers out of a false sense of humility because he was the youngest in the company. When John pointed to Petronius and said, "This man is a deacon," Petronius denied it. John took the younger man's hand and kissed it, while saying: "My son, take care never to deny the grace you have received from God, lest humility betray you into a lie. We must never lie, under any presence of good whatever, because no untruth can be from God."

When one of the company begged for a cure, Saint John answered replied that such diseases are beneficial to the soul. Nevertheless, he blessed some oil and gave it to the monk, who vomited and was from that moment perfectly cured.

When they next visited him, John bore a joyful countenance-- evidence of the joy of his soul. They talked about their journey from Jerusalem, then he provided the monks with a long discourse about banishing pride and vanity from their hearts in order to attain all other virtues. He provided examples of many monks, who, by secretly harboring vanity, fell also into scandalous irregularities, including one who, after living a most holy and austere life, fell into fornication because of his vanity and then, through despair, into all manner of disorders. He told of another who left his solitude to seek fame, but through a sermon he preached in a monastery along the way, was mercifully converted and became an eminent penitent.

After entertaining Saint Petronius and his fellows for three days, Saint John gave them his blessing. As they were preparing to leave, he said, "Go in peace, my children. Today Alexandria receives news of Prince Theodosius's victory over the tyrant Eugenius, but this excellent emperor will soon end his life by a natural death."

ST. JOHN was born about the year 305, was of a mean extraction, and brought up to the trade of a carpenter. At twenty-five years of age he forsook the world, and put himself under the guidance and direction of an ancient holy anchoret, with such an extraordinary humility and simplicity as struck the venerable old man with admiration; who inured him to obedience by making him water a dry stick for a whole year, as if it were a live plant, and perform several other things as seemingly ridiculous, all which he executed with the utmost fidelity. To the saint’s humility and ready obedience, Cassian 1 attributes the extraordinary gifts he afterwards received from God. He seems to have lived about twelve years with this old man, till his death, and about four more in different neighbouring monasteries.

Being about forty years of age, he retired alone to the top of a rock of very difficult ascent, near Lycopolis. 2 His cell he walled up, leaving only a little window through which he received all necessaries, and spoke to those who visited him what might be for their spiritual comfort and edification. During five days in the week he conversed only with God: but on Saturdays and Sundays all but women had free access to him for his instructions and spiritual advice. He never eat till after sunset, and then very sparingly; but never any thing that had been dressed by fire, not so much as bread. In this manner did he live from the fortieth or forty-second to the ninetieth year of his age. For the reception of such as came to him from remote parts, he permitted a kind of hospital to be built near his cell or grotto, where some of his disciples took care of them. He was illustrious for miracles, and a wonderful spirit of prophecy, with the power of discovering to those that came to see him, their most secret thoughts and hidden sins. And such was the fame of his predictions, and the lustre of his miracles which he wrought on the sick, by sending them some oil which he had blessed, that they drew the admiration of the whole world upon him.

Theodosius the Elder was then emperor, and was attacked by the tyrant Maximus, become formidable by the success of his arms, having slain the Emperor Gratian in 383, and dethroned Valentinian in 387. The pious emperor, finding his army much inferior to that of his adversary, caused this servant of God to be consulted concerning the success of the war against Maximus. Our saint foretold him, that he should be victorious almost without blood. The emperor, full of confidence in the prediction, marched into the West, defeated the more numerous armies of Maximus twice in Pannonia; crossed the Alps, took the tyrant in Aquileia, and suffered his soldiers to cut off his head. He returned triumphant to Constantinople, and attributed his victories very much to the prayers of St. John, who also foretold him the events of his other wars, the incursions of Barbarians, and all that was to befall his empire. Four years after, in 392, Eugenius, by the assistance of Arbogastes, who had murdered the Emperor Valentinian the Younger, usurped the empire of the West. Theodosius sent Eutropius the Eunuch into Egypt, with instructions to bring St. John with him to Constantinople, if it were possible; but that if he could not prevail with him to undertake the journey, to consult whether it was God’s will that he should march against Eugenius, or wait his arrival in the East. The man of God excused himself as to his journey to court, but assured Eutropius that his prince should be victorious, but not without loss and blood: as also that he would die in Italy, and leave the empire of the West to his son; all which happened accordingly. Theodosius marched against Eugenius, and in the first engagement lost ten thousand men, and was almost defeated: but renewing the battle on the next day, the 6th of September, in 394, he gained an entire victory by the miraculous interposition of heaven, as even Claudian, the heathen poet, acknowledges. Theodosius died in the West, on the 17th of January, in 395, leaving his two sons emperors, Arcadius in the East, and Honorius in the West.

This saint restored sight to a senator’s wife by some of the oil he had blessed for healing the sick. It being his inviolable custom never to admit any woman to speak to him, this gave occasion to a remarkable incident related by Evagrius, Palladius, and St. Austin, in his treatise of Care for the Dead. A certain general officer in the emperor’s service, visiting the saint, conjured him to permit his wife to speak to him; for she was come to Lycopolis, and had gone through many dangers and difficulties to enjoy that happiness. The holy man answered, that during his stricter enclosure for the last forty years since he had shut himself up in that rock, he had imposed on himself an inviolable rule not to see or converse with women; so he desired to be excused the granting her request. The officer returned to Lycopolis very melancholy. His wife, who was a person of great virtue, was not to be satisfied. The husband went back to the blessed man, told him she would die of grief if he refused her request. The saint said to him: “Go to your wife, and tell her that she shall see me to-night, without coming hither, or stirring out of her house.” This answer he carried to her, and both were very earnest to know in what manner the saint would perform his promise. When she was asleep in the night the man of God appeared to her in her dream, and said: “Your great faith, woman, obliged me to come to visit you; but I must admonish you to curb the like desires of seeing God’s servants on earth. Contemplate only their life, and imitate their actions. As for me, why did you desire to see me? Am I a saint, or a prophet like God’s true servants? I am a sinful and weak man. It is therefore, only in virtue of your faith that I have had recourse to our Lord, who grants you the cure of the corporal diseases with which you are afflicted. Live always in the fear of God, and never forget his benefits.” He added several proper instructions for her conduct, and disappeared. The woman awaking, described to her husband the person she had seen in her dream, with all his features, in such a manner as to leave no room to doubt but it was the blessed man that had appeared to her. Whereupon he returned the next day to give him thanks for the satisfaction he had vouchsafed his wife. But the saint on his arrival prevented him, saying: “I have fulfilled your desire, I have seen your wife, and satisfied her in all things she had asked: go in peace.” The officer received his benediction, and continued his journey to Seyne. What the man of God foretold happened to him, as, among other things, that he should receive particular honours from the emperor. Besides, the authors of the saint’s life, St. Austin relates this history which he received from a nobleman of great integrity and credit, who had it from the very persons to whom it happened. St. Austin adds, had he seen St. John, he would have inquired of him, whether he himself really appeared to this woman, or whether it was an angel in his shape, or whether the vision only passed in her imagination. 3

In the year 394, a little before the saint’s death, he was visited by Palladius, afterwards bishop of Helenopolis, who is one of the authors of his life. Several anchorets of the deserts of Nitria, all strangers, the principal of whom were Evagrius, Albinus, Ammonius, had a great desire to see the saint. Palladius, one of this number, being young, set out first in July, when the flood of the Nile was high. Being arrived at his mountain, he found the door of his porch shut, and that it would not be open till the Saturday following. He waited that time in the lodgings of strangers. On Saturday, at eight o’clock, Palladius entered the porch, and saw the saint sitting before his window, and giving advice to those who applied to him for it. Having saluted Palladius by an interpreter, he asked him of what country he was, and what was his business, and if he was not of the company or monastery of Evagrius? Palladius owned he was. In the mean time arrived Alypius, governor of the province, in great haste. The saint, on the arrival of Alypius, broke off his discourse with Palladius, who withdrew to make room for the governor to discourse with the saint. Their conversation was very long, and Palladius being weary, murmured within himself against the venerable old man, as guilty of exception of persons. He was even just going away, when the saint, knowing his secret thoughts, sent Theodorus, his interpreter, to him, saying: “Go, bid that brother not to be impatient: I am going to dismiss the governor, and then will speak to him.” Palladius, astonished that his thoughts should be known to him, waited with patience. As soon as Alypius was gone, St. John called Palladius, and said to him: “Why were you angry, imputing to me in your mind what I was no way guilty of? To you I can speak at any other time, and you have many fathers and brethren to comfort and direct you in the paths of salvation. But this governor being involved in the hurry of temporal affairs, and being come to receive some wholesome advice during the short time his affairs will allow him to breathe in, how could I give you the preference?” He then told Palladius what passed in his heart, and his secret temptations to quit his solitude; for which end the devil represented to him his father’s regret for his absence, and that he might induce his brother and sister to embrace a solitary life. The holy man bade him despise such suggestions; for they had both already renounced the world, and his father would yet live seven years. He foretold him that he should meet with great persecutions and sufferings, and should be a bishop, but with many afflictions: all which came to pass, though at that time extremely improbable.

The same year, St. Petronius, with six other monks, made a long journey to pay St. John a visit. He asked them if any amongst them were in holy orders? They said: No. One however, the youngest in the company, was a deacon, though this was unknown to the rest. The saint, by divine instinct, knew this circumstance, and that the deacon had concealed his orders out of a false humility, not to seem superior to the others, but their inferior, as he was in age. Therefore, pointing to him, he said: “This man is a deacon.” The other denied it, upon the false persuasion that to lie with a view to one’s own humiliation was no sin. St. John took him by the hand, and kissing it, said to him: “My son, take care never to deny the grace you have received from God, lest humility betray you into a lie. We must never lie, under any pretence of good whatever, because no untruth can be from God.” The deacon received this rebuke with great respect. After their prayer together, one of the company begged of the saint to be cured of a certain ague. He answered: “You desire to be freed from a sickness which is beneficial to you. As nitre cleanses the body, so distempers and other chastisements purify the soul.” However, he blessed some oil and gave it to him: he vomited plentifully after it, and was from that moment perfectly cured. They returned to their lodgings, where by his orders they were treated with all proper civility, and cordial hospitality. When they went to him again, he received them with joyfulness in his countenance, which evidenced the interior spiritual joy of his soul; he bade them sit down, and asked them whence they came? They said from Jerusalem. He then made them a long discourse, in which he first endeavoured to show his own baseness; after which he explained the means by which pride and vanity are to be banished out of the heart, and all virtues to be acquired. He related to them the examples of many monks, who, by suffering their hearts to be secretly corrupted by vanity, at last fell also into scandalous irregularities; as of one, who, after a most holy and austere life, by this means fell into fornication, and then by despair into all manner of disorders; also of another, who, from vanity, fell into a desire of leaving his solitude; but by a sermon he preached to others, in a monastery on his road, was mercifully converted and became an eminent penitent. The blessed John thus entertained Petronius and his company for three days till the hour of None. When they were leaving him, he gave them his blessing, and said: “Go in peace, my children; and know that the news of the victory which the religious prince Theodosius has gained over the tyrant Eugenius is this day come to Alexandria: but this excellent emperor will soon end his life by a natural death.” Some days after their leaving him to return home, they were informed he had departed this life. Having been favoured by a foresight of his death, he would see nobody for the last three days. At end of this term he sweetly expired, being on his knees at prayer, towards the close of the year 394, or the beginning of 395. It might probably be on the 17th of October, on which day the Copths, or Egyptian Christians, keep his festival: the Roman and other Latin Martyrologies mark it on the 27th of March.

The solitude which the Holy Ghost recommends, and which the saints embraced, resembled that of Jesus Christ, being founded on the same motive or principle, having the same exercises and employments, and the same end. Christ was conducted by the Holy Ghost into the desert, and he there spent his time in prayer and fasting. Wo to those whom humour or passion lead into solitude, or who consecrate it not to God by mortification, sighs of penance, and hymns of divine praise. To those who thus sanctify their desert or cell, it will be an anticipated paradise, an abyss of spiritual advantages and comforts, known only to such as have enjoyed them. The Lord will change the desert into a place of delights, and will make the solitude a paradise, and a garden worthy of himself. 4 In it only joy and jubilee shall be seen, nothing shall be heard but thanksgiving and praise. It is the dwelling of a terrestrial seraph, whose sole employment is to labour to know, and correct all secret disorders of his own soul, to forget the world, and all objects of vanity which could distract or entangle him; to subdue his senses, to purify the faculties of his soul, and entertain in his heart a constant fire of devotion, by occupying it assiduously on God, Jesus Christ, and heavenly things, and banishing all superfluous desires and thoughts; lastly, to make daily progress in purity of conscience, humility, mortification, recollection, and prayer, and to find all his joy in the most fervent and assiduous adoration, love, and praise of his sovereign Creator and Redeemer.

Note 1. Coll. b. 4. c. 21. p. 81. [back]

Note 2. A city in the north of Thebais, in Egypt. [back]

Note 3. S. Aug. l. pro curâ de mortuis, c. 17. p. 294. [back]

Note 4. Isa. lxiii. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume III: March. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/3/271.html

John of Egypt (RM)

(also known as John of Lycopolis)

Born at Asyut (Assiut or Lycopolis), Egypt, c. 304; died near there in 394 or 395; feast is October 17 in the Coptic Church. John was a carpenter (or shoemaker) at Asyut who at 25 became a hermit on a neighboring mountain for the next 40 years. To test his humility and obedience the ancient anchorite who resided there made John perform seemingly ridiculous acts, such as water a dry stick for a whole year, all of which he executed with the utmost fidelity. He seems to have lived with the old hermit for the 12 years until the holy man's death, then spent four years in various monasteries.

When he was about 40, John walled himself into a cell on the top of a rock near Asyut, where he never ate until after sunset, and then very sparingly. Weekdays he spent his time in prayer. On Saturdays and Sundays, he spoke through the little window in his cell to the many men who came to him for instruction and spiritual advice. He allowed a type of hospital to be built near his cell, where some of his disciples took care of his visitors. These men were drawn by his reputation for miracles of healing, gift of prophecy, and ability to read souls.

Saint John's gift for foretelling the future was such that he was given the surname `Prophet of the Thebaid.' When Emperor Theodosius the Elder was attacked by the tyrant Maximus, who had killed Emperor Gratian in 383 and dethroned Valentinian in 387, he consulted John about the proposed war against Maximus. John foretold that Theodosius would be victorious, almost without blood. The emperor, full of confidence, marched into the West, defeated the more numerous armies of Maximus twice in Pannonia; crossed the Alps, took the tyrant in Aquileia. He returned triumphant to Constantinople, and attributed his victories to the prayers of Saint John, who also foretold him the events of his other wars, the incursions of barbarians, and all that was to befall his empire.

In 392, Eugenius, by the assistance of Arbogastes, who had murdered the emperor Valentinian the Younger, usurped the empire of the West. Theodosius instructed Eutropins the Eunuch to try to bring John to Constantinople; if he would not come, Eutropins was to consult with the saint whether it was God's will that he should march against Eugenius, or wait his arrival in the East. John would not leave his cell but predicted the emperor's success, but this time many lives would be lost and Theodosius would die in Italy. Theodosius marched against Eugenius, and lost 10,000 men in the first engagement. He was almost defeated: but renewing the battle on the next day, September 6, 394, he was entirely victorious by the miraculous interposition of heaven, as even the heathen poet Claudian acknowledges. Theodosius died in the West, January 17, 395, leaving his two sons emperors (Arcadius in the East, and Honorius in the West).

Among Saint John's reported miracles was the restoration of sight to the wife of a senator through the vehicle of oil he blessed. It had to be through such a medium with women, for he refused to speak with any woman. One interesting incident is related by Evagrius, Palladius, and Augustine in his treatise of On the Care for the Dead. One of the emperor's officers begged John to allow his wife to speak to him. She had made the difficult and dangerous journey to Lycopolis for that purpose. The holy man answered, that during his stricter enclosure for the last forty years, he had imposed on himself an inviolable rule not to see or converse with women; so he desired to be excused the granting her request. The officer returned to his virtuous, but disappointed, wife, who begged her husband to try again.

Returning to John, the husband said that his wife would die of grief if he refused her request. The saint said to him: "Go to your wife, and tell her that she shall see me tonight, without coming hither or stirring out of her house." When she was asleep that night, the man of God appeared to her in her dream, and said: "Your great faith, woman, obliged me to come to visit you; but I must admonish you to curb the like desires of seeing God's servants on earth. Contemplate only their life, and imitate their actions. As for me, why did you desire to see me? Am I a saint or a prophet like God's true servants? I am a sinful and weak man. It is, therefore, only in virtue of your faith that I have had recourse to our Lord who grants you the cure of the corporal diseases with which you are afflicted. Live always in the fear of God, and never forget his benefits." He added several proper instructions for her conduct, and disappeared.

Upon awakening the woman described to her husband the person she had seen in her dream and he confirmed that it was John. Whereupon he returned the next day to thank him. But when he arrived, the saint would not permit it. The officer received his benediction, and continued his journey to Seyne.

In 394, Palladius, who later became bishop of Helenopolis and one of the authors of John's vita, visited the saint in July. When he arrived, he found that he would have to wait until Saturday to speak with John. He returned that day in the early morning, saw the saint sitting at his window talking with others. Through an interpreter, introductions were made and Palladius was identified as a member of Evagrius's community.

Their conversation was interrupted by the hasty arrival of Alypius, governor of the province, in great haste. John asked Palladius to step aside for the governor with whom the saint engaged in a long discussion while an increasingly impatient Palladius had to wait. The weary man began to complain internally that the saint was showing preference to rank. He was about to leave when John sent his interpreter to stop him saying, "Go, bid that brother not to be impatient: I am going to dismiss the governor, and then will speak to him."

Palladius, astonished that his thoughts should be known to him, waited patiently. When Alypius had left, John called Palladius, and asked: "Why were you angry, unjustly imputing guilt to me in your mind? To you I can speak at any other time, and you have many fathers and brethren to comfort and direct you in the paths of salvation. But this governor, being involved in the hurry of temporal affairs, and having come to receive some wholesome advice during the short time his affairs will allow him time to breathe in, how could I give you the preference?"

He then told Palladius what passed in his heart: his secret temptations to quit his solitude. He told Palladius that it was the devil who tempted him with images of his father's loneliness at his absence, and that he might induce his brother and sister to embrace a solitary life. The holy man told him to ignore such suggestions, because his siblings had already renounced the world, and his father would live seven more years. He foretold him that he should meet with great persecutions and sufferings, and should be a bishop, but with many afflictions: all which came to pass, though at that time extremely improbable. The text of Palladius's account of their meeting still exists.

That same year John was visited by Saint Petronius with six other monks. The hermit asked if any of them was in holy orders and they answered, "no." In fact, Petronius was a deacon but had not disclosed this to his fellow travellers out of a false sense of humility because he was the youngest in the company. When John pointed to Petronius and said, "This man is a deacon," Petronius denied it. John took the younger man's hand and kissed it, while saying: "My son, take care never to deny the grace you have received from God, lest humility betray you into a lie. We must never lie, under any presence of good whatever, because no untruth can be from God."

When one of the company begged for a cure, Saint John answered replied that such diseases are beneficial to the soul. Nevertheless, he blessed some oil and gave it to the monk, who vomited and was from that moment perfectly cured.

When they next visited him, John bore a joyful countenance-- evidence of the joy of his soul. They talked about their journey from Jerusalem, then he provided the monks with a long discourse about banishing pride and vanity from their hearts in order to attain all other virtues. He provided examples of many monks, who, by secretly harboring vanity, fell also into scandalous irregularities, including one who, after living a most holy and austere life, fell into fornication because of his vanity and then, through despair, into all manner of disorders. He told of another who left his solitude to seek fame, but through a sermon he preached in a monastery along the way, was mercifully converted and became an eminent penitent.

After entertaining Saint Petronius and his fellows for three days, Saint John gave them his blessing. As they were preparing to leave, he said, "Go in peace, my children. Today Alexandria receives news of Prince Theodosius's victory over the tyrant Eugenius, but this excellent emperor will soon end his life by a natural death."

A

few days later, the monks learned that Saint John had died. He had foreseen his

own death and refused to see anyone during the last three days. Instead, Saint

John spent his time in prayer and expired on his knees. Saint John's reputation

for holiness is said to have been second only to that of Saint Antony. He was

much admired by his contemporaries SS. Jerome, Augustine, and John Cassian, who

attributes the extraordinary gifts John received from God to the saint's

humility and ready obedience (Attwater, Attwater2, Benedictines, Gill,

Husenbeth).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0327.shtml

March 27

St. John of Egypt, Hermit

From Rufinus, in the second

book of the lives of the fathers; and from Palladius in his Lausiaca: this last

had often seen him. Also St. Jerom, St. Austin, Cassian, &c. See Tillemont,

t. 10. p. 9. See also the Wonders of God in the Wilderness, p. 160.

A.D. 394

ST. JOHN was born about the year 305, was of a mean extraction, and brought up to the trade of a carpenter. At twenty-five years of age he forsook the world, and put himself under the guidance and direction of an ancient holy anchoret, with such an extraordinary humility and simplicity as struck the venerable old man with admiration; who inured him to obedience by making him water a dry stick for a whole year, as if it were a live plant, and perform several other things as seemingly ridiculous, all which he executed with the utmost fidelity. To the saint’s humility and ready obedience, Cassian 1 attributes the extraordinary gifts he afterwards received from God. He seems to have lived about twelve years with this old man, till his death, and about four more in different neighbouring monasteries.

Being about forty years of age, he retired alone to the top of a rock of very difficult ascent, near Lycopolis. 2 His cell he walled up, leaving only a little window through which he received all necessaries, and spoke to those who visited him what might be for their spiritual comfort and edification. During five days in the week he conversed only with God: but on Saturdays and Sundays all but women had free access to him for his instructions and spiritual advice. He never eat till after sunset, and then very sparingly; but never any thing that had been dressed by fire, not so much as bread. In this manner did he live from the fortieth or forty-second to the ninetieth year of his age. For the reception of such as came to him from remote parts, he permitted a kind of hospital to be built near his cell or grotto, where some of his disciples took care of them. He was illustrious for miracles, and a wonderful spirit of prophecy, with the power of discovering to those that came to see him, their most secret thoughts and hidden sins. And such was the fame of his predictions, and the lustre of his miracles which he wrought on the sick, by sending them some oil which he had blessed, that they drew the admiration of the whole world upon him.

Theodosius the Elder was then emperor, and was attacked by the tyrant Maximus, become formidable by the success of his arms, having slain the Emperor Gratian in 383, and dethroned Valentinian in 387. The pious emperor, finding his army much inferior to that of his adversary, caused this servant of God to be consulted concerning the success of the war against Maximus. Our saint foretold him, that he should be victorious almost without blood. The emperor, full of confidence in the prediction, marched into the West, defeated the more numerous armies of Maximus twice in Pannonia; crossed the Alps, took the tyrant in Aquileia, and suffered his soldiers to cut off his head. He returned triumphant to Constantinople, and attributed his victories very much to the prayers of St. John, who also foretold him the events of his other wars, the incursions of Barbarians, and all that was to befall his empire. Four years after, in 392, Eugenius, by the assistance of Arbogastes, who had murdered the Emperor Valentinian the Younger, usurped the empire of the West. Theodosius sent Eutropius the Eunuch into Egypt, with instructions to bring St. John with him to Constantinople, if it were possible; but that if he could not prevail with him to undertake the journey, to consult whether it was God’s will that he should march against Eugenius, or wait his arrival in the East. The man of God excused himself as to his journey to court, but assured Eutropius that his prince should be victorious, but not without loss and blood: as also that he would die in Italy, and leave the empire of the West to his son; all which happened accordingly. Theodosius marched against Eugenius, and in the first engagement lost ten thousand men, and was almost defeated: but renewing the battle on the next day, the 6th of September, in 394, he gained an entire victory by the miraculous interposition of heaven, as even Claudian, the heathen poet, acknowledges. Theodosius died in the West, on the 17th of January, in 395, leaving his two sons emperors, Arcadius in the East, and Honorius in the West.

This saint restored sight to a senator’s wife by some of the oil he had blessed for healing the sick. It being his inviolable custom never to admit any woman to speak to him, this gave occasion to a remarkable incident related by Evagrius, Palladius, and St. Austin, in his treatise of Care for the Dead. A certain general officer in the emperor’s service, visiting the saint, conjured him to permit his wife to speak to him; for she was come to Lycopolis, and had gone through many dangers and difficulties to enjoy that happiness. The holy man answered, that during his stricter enclosure for the last forty years since he had shut himself up in that rock, he had imposed on himself an inviolable rule not to see or converse with women; so he desired to be excused the granting her request. The officer returned to Lycopolis very melancholy. His wife, who was a person of great virtue, was not to be satisfied. The husband went back to the blessed man, told him she would die of grief if he refused her request. The saint said to him: “Go to your wife, and tell her that she shall see me to-night, without coming hither, or stirring out of her house.” This answer he carried to her, and both were very earnest to know in what manner the saint would perform his promise. When she was asleep in the night the man of God appeared to her in her dream, and said: “Your great faith, woman, obliged me to come to visit you; but I must admonish you to curb the like desires of seeing God’s servants on earth. Contemplate only their life, and imitate their actions. As for me, why did you desire to see me? Am I a saint, or a prophet like God’s true servants? I am a sinful and weak man. It is therefore, only in virtue of your faith that I have had recourse to our Lord, who grants you the cure of the corporal diseases with which you are afflicted. Live always in the fear of God, and never forget his benefits.” He added several proper instructions for her conduct, and disappeared. The woman awaking, described to her husband the person she had seen in her dream, with all his features, in such a manner as to leave no room to doubt but it was the blessed man that had appeared to her. Whereupon he returned the next day to give him thanks for the satisfaction he had vouchsafed his wife. But the saint on his arrival prevented him, saying: “I have fulfilled your desire, I have seen your wife, and satisfied her in all things she had asked: go in peace.” The officer received his benediction, and continued his journey to Seyne. What the man of God foretold happened to him, as, among other things, that he should receive particular honours from the emperor. Besides, the authors of the saint’s life, St. Austin relates this history which he received from a nobleman of great integrity and credit, who had it from the very persons to whom it happened. St. Austin adds, had he seen St. John, he would have inquired of him, whether he himself really appeared to this woman, or whether it was an angel in his shape, or whether the vision only passed in her imagination. 3

In the year 394, a little before the saint’s death, he was visited by Palladius, afterwards bishop of Helenopolis, who is one of the authors of his life. Several anchorets of the deserts of Nitria, all strangers, the principal of whom were Evagrius, Albinus, Ammonius, had a great desire to see the saint. Palladius, one of this number, being young, set out first in July, when the flood of the Nile was high. Being arrived at his mountain, he found the door of his porch shut, and that it would not be open till the Saturday following. He waited that time in the lodgings of strangers. On Saturday, at eight o’clock, Palladius entered the porch, and saw the saint sitting before his window, and giving advice to those who applied to him for it. Having saluted Palladius by an interpreter, he asked him of what country he was, and what was his business, and if he was not of the company or monastery of Evagrius? Palladius owned he was. In the mean time arrived Alypius, governor of the province, in great haste. The saint, on the arrival of Alypius, broke off his discourse with Palladius, who withdrew to make room for the governor to discourse with the saint. Their conversation was very long, and Palladius being weary, murmured within himself against the venerable old man, as guilty of exception of persons. He was even just going away, when the saint, knowing his secret thoughts, sent Theodorus, his interpreter, to him, saying: “Go, bid that brother not to be impatient: I am going to dismiss the governor, and then will speak to him.” Palladius, astonished that his thoughts should be known to him, waited with patience. As soon as Alypius was gone, St. John called Palladius, and said to him: “Why were you angry, imputing to me in your mind what I was no way guilty of? To you I can speak at any other time, and you have many fathers and brethren to comfort and direct you in the paths of salvation. But this governor being involved in the hurry of temporal affairs, and being come to receive some wholesome advice during the short time his affairs will allow him to breathe in, how could I give you the preference?” He then told Palladius what passed in his heart, and his secret temptations to quit his solitude; for which end the devil represented to him his father’s regret for his absence, and that he might induce his brother and sister to embrace a solitary life. The holy man bade him despise such suggestions; for they had both already renounced the world, and his father would yet live seven years. He foretold him that he should meet with great persecutions and sufferings, and should be a bishop, but with many afflictions: all which came to pass, though at that time extremely improbable.

The same year, St. Petronius, with six other monks, made a long journey to pay St. John a visit. He asked them if any amongst them were in holy orders? They said: No. One however, the youngest in the company, was a deacon, though this was unknown to the rest. The saint, by divine instinct, knew this circumstance, and that the deacon had concealed his orders out of a false humility, not to seem superior to the others, but their inferior, as he was in age. Therefore, pointing to him, he said: “This man is a deacon.” The other denied it, upon the false persuasion that to lie with a view to one’s own humiliation was no sin. St. John took him by the hand, and kissing it, said to him: “My son, take care never to deny the grace you have received from God, lest humility betray you into a lie. We must never lie, under any pretence of good whatever, because no untruth can be from God.” The deacon received this rebuke with great respect. After their prayer together, one of the company begged of the saint to be cured of a certain ague. He answered: “You desire to be freed from a sickness which is beneficial to you. As nitre cleanses the body, so distempers and other chastisements purify the soul.” However, he blessed some oil and gave it to him: he vomited plentifully after it, and was from that moment perfectly cured. They returned to their lodgings, where by his orders they were treated with all proper civility, and cordial hospitality. When they went to him again, he received them with joyfulness in his countenance, which evidenced the interior spiritual joy of his soul; he bade them sit down, and asked them whence they came? They said from Jerusalem. He then made them a long discourse, in which he first endeavoured to show his own baseness; after which he explained the means by which pride and vanity are to be banished out of the heart, and all virtues to be acquired. He related to them the examples of many monks, who, by suffering their hearts to be secretly corrupted by vanity, at last fell also into scandalous irregularities; as of one, who, after a most holy and austere life, by this means fell into fornication, and then by despair into all manner of disorders; also of another, who, from vanity, fell into a desire of leaving his solitude; but by a sermon he preached to others, in a monastery on his road, was mercifully converted and became an eminent penitent. The blessed John thus entertained Petronius and his company for three days till the hour of None. When they were leaving him, he gave them his blessing, and said: “Go in peace, my children; and know that the news of the victory which the religious prince Theodosius has gained over the tyrant Eugenius is this day come to Alexandria: but this excellent emperor will soon end his life by a natural death.” Some days after their leaving him to return home, they were informed he had departed this life. Having been favoured by a foresight of his death, he would see nobody for the last three days. At end of this term he sweetly expired, being on his knees at prayer, towards the close of the year 394, or the beginning of 395. It might probably be on the 17th of October, on which day the Copths, or Egyptian Christians, keep his festival: the Roman and other Latin Martyrologies mark it on the 27th of March.