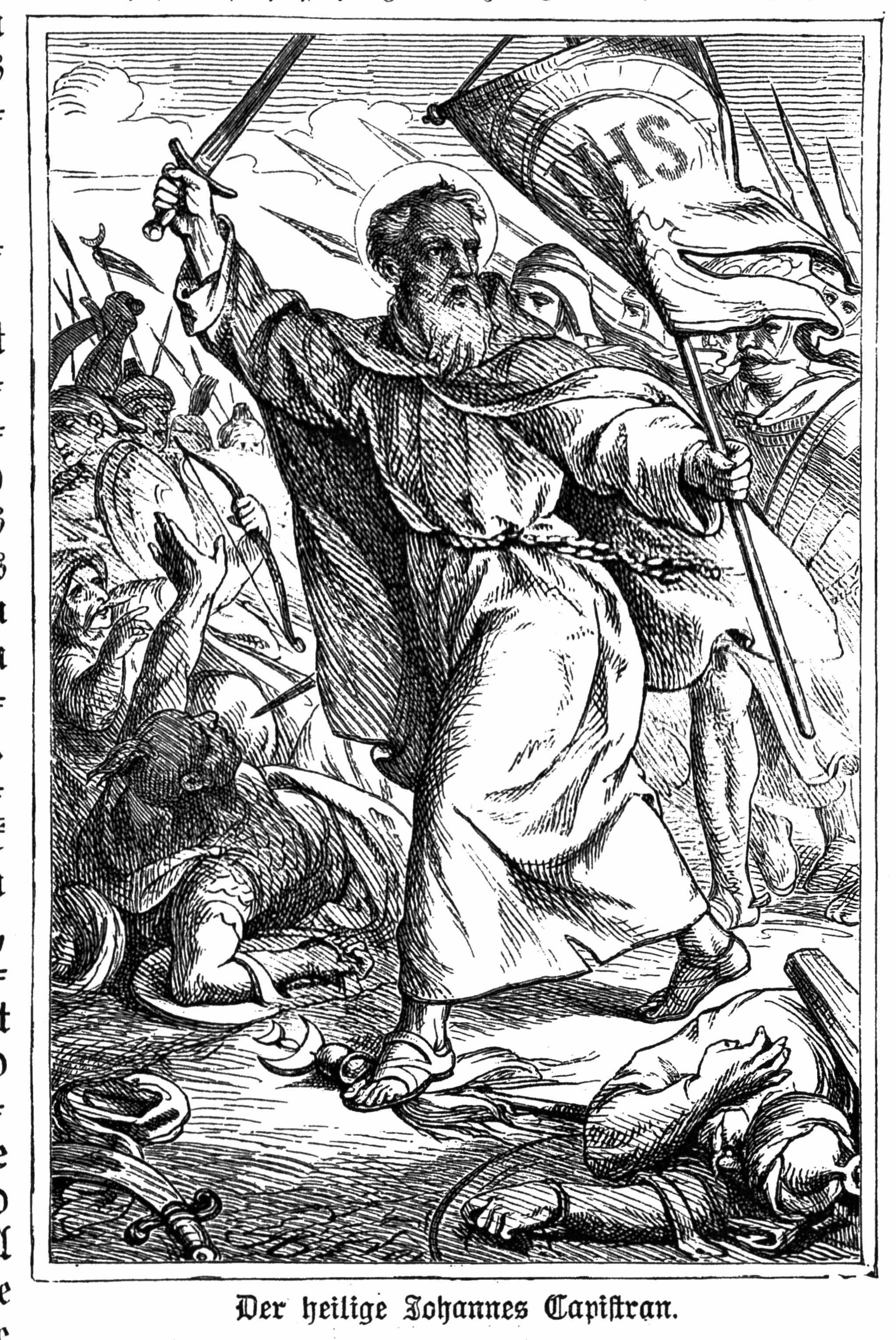

Saint Jean de Capistran

Frère mineur (+ 1456)

Martyrologe romain

...de même que le soleil se lève pour le monde dans

les hauteurs de Dieu, que la lumière du clerc brille devant les hommes afin

qu'en voyant ce que font de bien ces serviteurs de Dieu, les hommes rendent

gloire au Père qui est aux cieux...

'miroir des clercs', S. Jean de Capistran

Saint Jean de Capistran

Franciscain

(† 1456)

Jean, né à Capistrano, dans l'Abruzze, était fils d'un

gentilhomme français qui avait suivi à Naples le duc d'Anjou, devenu roi de ce

pays. Après ses humanités, il fut envoyé à Pérouse pour y étudier le droit

canonique et civil. On le pourvut d'une place de judicature, et un homme riche

et noble, charmé de ses qualités éminentes, lui donna sa fille en mariage. Tout

lui souriait dans le monde, quand tout à coup s'évanouirent ces flatteuses

espérances.

Dans une guerre contre le roi de Naples, la ville de

Pérouse le soupçonna de prendre le parti de ce prince; on le fit arrêter.

Malgré son innocence et son éloquence à se défendre, il fut jeté en prison. Sur

ces entrefaites sa femme étant morte, il résolut de ne plus servir que Dieu.

Il vendit tous ses biens, paya sa rançon, distribua le

reste aux pauvres, et se réfugia chez les Franciscains, au monastère du Mont,

près de Pérouse. Le gardien, craignant que cette vocation ne fût l'effet d'un

dépit passager plutôt que d'un mouvement de la grâce, voulut l'éprouver. Il lui

ordonna de faire le tour de la ville de Pérouse dont il avait été gouverneur,

monté à rebours sur un âne, couvert d'un mauvais habit et la tête coiffée d'un

bonnet de carton où étaient écrits divers péchés. Après une telle épreuve, les

humiliations du noviciat ne lui coûtèrent plus.

On lui donna pour maître un simple frère convers, à la

direction duquel Jean se soumit avec la simplicité d'un enfant. Il fut traité

par lui avec dureté:

"Je rends grâces au Seigneur, disait-il plus

tard, de m'avoir donné un tel guide; s'il n'eût usé envers moi de pareilles

rigueurs, jamais je n'aurais pu acquérir l'humilité et la patience."

Jean fut renvoyé par deux fois du noviciat comme

incapable de remplir jamais aucun emploi dans la religion. Il resta jour et

nuit à la porte du couvent, souffrant avec joie l'indifférence des religieux,

les railleries des passants et les mépris des pauvres qui venaient demander

l'aumône. Une persévérance si héroïque désarma la sévérité des supérieurs et

dissipa leurs craintes. Jean, reçu de nouveau, fut enfin admis à la profession.

Dès lors sa vie fut admirable: il ne mangeait qu'une

fois le jour, et, durant trente-six ans coucha sur le plancher de sa cellule,

dormant au plus trois heures. Vêtu d'un habit cousu de pièces, il marchait les

pieds nus, sans socques ni sandales, et il macérait son corps par des

disciplines sanglantes et de rudes cilices. Mort à lui-même, il vivait

uniquement de Jésus sur la Croix. Embrasé d'amour pour Dieu, il faisait de sa

vie une oraison continuelle: le Crucifix, le Tabernacle, l'image de Marie, le

jetaient dans l'extase: "Dieu, disait-il, m'a donné le nom de Jean, pour

me faire le fils de Marie et l'ami de Jésus."

Ordonné prêtre, Jean fut appliqué au ministère de la

parole. Souvent les larmes et les sanglots de ses auditeurs interrompaient ses

prédications, ses paroles produisaient partout des conversions nombreuses. Une

secte monstrueuse de prétendus moines, les Fraticelli, dont les erreurs et les

moeurs scandalisaient l'Église, fut anéantie par son zèle et sa charité. Le

Pape Eugène IV, frappé des prodigieux succès de ses discours, l'envoya comme

nonce en Sicile; puis le chargea de travailler, au concile de Florence, à la

réunion des Latins et des Grecs. Enfin il le députa vers le roi de France,

Charles VII.

Ami de saint Bernardin de Sienne, il le défendit,

devant la cour de Rome, contre les calomnies que lui attirait son ardeur pour

la réforme de son Ordre; il l'aida grandement dans cette entreprise, et il alla

lui-même visiter les maisons établies en Orient.

Nicolas V l'envoya, en qualité de commissaire

apostolique, dans la Hongrie, l'Allemagne, la Bohème et la Pologne. Toutes

sortes de bénédictions accompagnèrent ses pas: clergé, communautés religieuses,

nobles et peuples, participaient aux bénignes influences de sa charité. Il

ramena au bercail de l'Église un grand nombre de schismatiques et d'hérétiques,

et, à la vraie religion, une quantité prodigieuse de Juifs et même de

Musulmans.

À cette époque, Mahomet II menaçait l'Occident d'une

complète invasion, tenait Belgrade assiégée, et, fier de ses victoires, se

promettait d'arborer le croissant dans l'enceinte même de Rome. Le Pape Calixte

III chargea saint Jean de Capistran de prêcher une croisade: à la voix

puissante de cet ami de Dieu, une armée de 40,000 hommes se leva; il la

disciplina pour les combats du Ciel; il lui trouva pour chef Huniade, un héros,

et il la conduisit à la victoire.

Étant à trois journées de marche des Turcs, tandis

qu'il célébrait la Messe en plein air dans les grandes plaines du Danube, une

flèche partie d'en haut vint, pendant le Saint Sacrifice, se placer sur le

corporal. Après la Messe, le Saint lut ces mots écrits en lettres d'or sur le

bois de la flèche:

"Par le secours de Jésus, Jean de Capistran

remportera la victoire." Au fort de la mêlée, il tenait en main l'étendard

de la Croix et criait:

"Victoire, Jésus, victoire!" Belgrade fut

sauvée. C'était en l'an 1456.

Trois mois après, saint Jean de Capistran, ayant

prononcé ces paroles du Nunc dimittis: "C'est maintenant, Seigneur, que

Vous laisserez mourir en paix Votre serviteur," expira en disant une

dernière fois: Jésus. Il avait soixante-et-onze ans.

Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes, Vie des Saints, p.

137-139

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jean_de_capistran.html

Predigt des heiligen Johannes Capistranus bei St.

Stephan (1451)

Feder- und Pinselzeichnung in Braun mit Weißhöhungen über Bleistift von Karl

Ruß. Blatt 122 aus dem Zyklus „Bilder zur Geschichte von Wien“. Die 149

Zeichnungen entstanden zwischen 27. Jänner 1826 und 12. Dezember 1832.

Kapisztrán Szent János Itália után 1451-től a német

területeken folytatta a női hiúság és a szerencsejátékok elleni prédikációit.

Bécsben az 1451. év böjti idõszakában tartott prédikációk alkalmával máglyára

is sor került, ahol maga a királynõ dobta előként sakkjátékát és hajdíszét a

tûzbe

23 octobre

Saint Jean de Capistran

Saint Jean de Capistran naquit au royaume de Naples,

près d'Aquila, à Capistran, dans les Abruzzes, le 24 juin 1386, d’un noble

seigneur, sans doute angevin mais peut-être savoyard, qui avait suivi Louis I°

d'Anjou[1] dans la conquête du royaume de Naples,

et, après avoir épousé une personne de rare piété, s'était fixé à Capistran.

Très tôt orphelin de père, Jean fut initié par sa mère aux premiers éléments,

puis fut envoyé à Pérouse où, pendant dix ans, il étudia si brillamment le

droit civil et canonique que ses maîtres, le considérant comme le prince

des jurisconsultes, recouraient à son jugement dans les questions épineuses.

Nommé gouverneur de Pérouse[2] par le roi Ladislas[3] (1412), Jean étant pour tous un juge

intègre et incorruptible, traita sévèrement les fauteurs de désordre. Un

seigneur tenta de le soudoyer pour obtenir une sentence de mort contre un

ennemi, mais Jean ayant soigneusement étudié le cas et reconnu l'innocence de

l'accusé, le libéra en dépit des menaces de l’accusateur.

En 1415, il allait épouser la fille d'un riche

pérugin, quand, négociant la paix entre Pérouse et de Rimini, il fut trahi et

enfermé, les fers aux pieds, dans une tour de Rimini. En s'évadant le long de

la muraille extérieure, il tomba et se brisa le pied ; ressaisi, il fut

jeté dans un cachot souterrain où, épuisé, révolté et livré à de tristes réflexions,

il s'endormit.

« Lui apparut dans les airs un homme vêtu de

l’habit des Franciscains, s’adressant ainsi à lui : “ A qui parles-tu avec tant

d’arrogance ? ” Jean lui dit plein de terreur : “ Qu’est-ce que Dieu veut de

moi ? ” Et l’homme lui répondit : “ Ne vois-tu pas ce que Dieu a choisi de

faire de toi ? Ne vois-tu pas cet habit que je porte ? A ce monde tu

enseigneras la Religion. ” Jean répondit : “ Je ferai ce que Dieu ordonne

et je la proclamerai puisque telle est la volonté de Dieu. ” - L’homme

vêtu de l’habit des Frères mineurs, plongeant son regard dans le sien ; il le

regarda avec tant de tendresse que son cœur fondit et de ses yeux jaillirent

comme des torrents de larmes et de ses entrailles sortirent de profonds

soupirs. - L’homme disparut mais il eut une autre vision : lui fut

montrée la terre presque dans l’obscurité, dans une ombre épaisse et au milieu

des ténèbres demeurait un rayon de lumière et vers cette lumière affluaient de

nombreux peuples, des foules innombrables. Toujours il pensa et crut que cet

homme lui était apparu était le bienheureux François. Personne ne peut nier que

les peuples s’acheminant vers la lumière fussent les Italiens, les Allemands,

les Bohémiens, les Hongrois, les habitants de la Transylvanie et de la Valachie,

les Russes et les Slaves ; et le rayon de lumière était Jean lui-même qui

répandit la doctrine divine. »

Libéré au prix d'une forte rançon, Jean vendit ses

biens, rendit la dot à sa fiancée, distribua aux pauvres le reste de ce qu'il

possédait et demanda son admission chez les Observants del Monte, près de

Pérouse. Pour éprouver sa vocation Marc de Bergame lui dit : « Les

couvents ne sont point le refuge des vagabonds et de quiconque est fatigué du

siècle ; il faut bien d'autres preuves pour entrer dans un ordre

religieux ; je ne vous admettrai que quand vous aurez dit un adieu

solennel au monde et à toute vanité terrestre. » Jean parcourut les rues

de Pérouse, monté à rebours sur un âne, couvert de haillons et coiffé d'une

mitre de carton sur laquelle étaient écrits en gros caractères tous les péchés

de sa vie ; la populace le considérant comme un insensé, l'accabla de ses

moqueries et de ses injures.

A la suite de cette épreuve, Jean fut admis au couvent

des franciscains de Pérouse (4 octobre 1416) et placé sous la direction

d'Onuphre de Seggiano, simple frère lai, mais religieux d'une rare prudence et

d'une haute sainteté : il travailla dès lors à se dépouiller du vieil

homme pour revêtir le nouveau, se montra assidu à l'oraison, plein de zèle et

de charité à l'égard de ses frères malades, donna l'exemple d'une obéissance

aveugle dans la pratique des plus rigoureuses austérités.

Le noviciat fut marqué pour Jean par de grandes

humiliations, de fortes réprimandes, de rudes souffrances corporelles. Un jour

que les novices devaient laver les tuniques, les frères n'osaient commencer le

travail parce que l'eau dans laquelle trempaient les tuniques était toute

bouillante ; survint alors le frère Onuphre qui, sans rien dire aux

autres, adressa de vifs reproches à Jean, l’accusant de négligence et de

paresse, puis tirant de l'eau bouillante une tunique, il la lui jeta au visage.

Sentant son visage brûlé, Jean se jeta à genoux devant son supérieur, mais

aucune trace de brûlure ne paraissait sur sa face.

Admis bientôt à faire sa profession, l'humble

religieux redoubla de ferveur dans l'accomplissement des tâches, singulièrement

des plus bas offices. Jean de Caspistran étudia ensuite

la théologie avec saint Jacques de La Marche[4], et eut pour premier maître saint Bernardin

de Sienne[5]. Celui-ci ne tarda pas à constater les

progrès surprenants de son élève : un jour, il dit en parlant de

lui : « Jean apprend en dormant ce que d'autres n'apprennent qu'en

travaillant jour et nuit. »

Jean de Capistran qui semblait avoir reçu la science

infuse, se montra profond théologien, savant canoniste et le plus grand

missionnaire de son temps. Disciple de saint Bernardin de Sienne, il en saisit

le secret : humilité, prière et pénitence, comptant avant tout sur la

grâce divine pour surmonter les obstacles. Vers 1420, Jean était diacre quand

saint Bernardin le fit prêcher à Sienne et en Toscane. Ordonné prêtre, vers

1425, il ne s’accorda plus de repos, parcourant l’Italie pour combattre toutes

les erreurs, attaquer toutes les sectes, et ramener à Dieu des milliers de

pécheurs, de juifs, d’hérétiques et de schismatiques ; la sainteté de sa

vie forçait au silence ceux qui refusaient la conversion. Dans toute l'Italie,

les populations accouraient en foule pour l'entendre.

Martin V, Eugène IV, Nicolas V et Calixte III, eurent

recours à Jean dont ils firent un nonce apostolique, un légat a latere et

un inquisiteur général. Contre les excès des fratricelles qui s'étaient

multipliés en Italie à la faveur du Grand Schisme d’Occident, Martin V donna

d’amples pouvoirs à Jean de Capistran et à Jacques de la Marche (1426) ;

l'erreur, un instant comprimée par l'éloquence, le courage et la charité des

deux franciscains, se réveilla plus menaçante, aussi mandaté par Eugène IV

(1432) et Nicolas V (1447) Jean de Capistran poursuivit l'hérésie sans se

soucier des fatigues ou par des périls. Un jour, en rase campagne, il s'éloigna

de ses compagnons pour prier ; des hérétiques, ne sachant pas qui il

était, lui demandèrent d'un air furieux où était le frère Jean de Capistran ;

comprenant le danger, mais ne voulant pas se sauver par un mensonge, répondit

d'une voix ferme : C'est moi qui suis Jean de Capistran ! Frappés

d'une terreur soudaine, les sectaires ne lui firent aucun mal. Jean de

Capistran, comme son maître Bernardin, appuyait son enseignement sur le

Nom de Jésus dont il proclamait les gloires.

Quand il apprit que Bernardin était persécuté à cause

de cette dévotion, il accourut à Rome pour plaider la cause de son maître

auprès de Martin V. Il assista Martin V dans sa dernière maladie, et prédit à

Eugène IV sa prochaine élection ; il examina, avec saint Laurent Justinien, la

cause des disciples de Jean Colombini[6], les Jésuates, soupçonnés d’avoir parti lié

avec les fratricelles, qui criaient : « Vive le Christ et la riche

sainte pauvreté que nous avons choisie pour épouse ! » Il attesta leur

innocence (1437). Vers 1439, nommé visiteur des couvents franciscains de Terre

Sainte, Jean de Capistran travailla à l’union des Arméniens dont il ramena des

représentants au concile de Florence[7]. Il s’opposa à l'antipape Félix V, et fut

légat d’Eugène IV en Milanais et en Bourgogne ; il gagna Philippe Visconti[8] à la cause de Rome, puis, passant en

Bourgogne, il y fut reçu comme un ange du ciel.

Après le concile de Florence Jean, nommé nonce

apostolique en Sicile, s'arrêta au couvent du lac Trasimène où il vit pour la

dernière fois Bernardin de Sienne. A Palerme, il préféra au palais une cellule

du couvent où il remplit les plus humbles offices. A la mort de Bernardin, il

vint à Aquila pour être témoin des miracles accomplis sur son tombeau et

prépara sa canonisation. Il prêcha en Italie la croisade contre les Turcs, puis

fut légat en France. A Eugène IV, il refusa l'évêché d'Aquila, pour continuer

la vie du cloître et les travaux du ministère apostolique ; profondément

touché, le pape n'insista pas davantage pour l'évêché de Rietti.

Continuant de remplir des charges importantes sous

Nicolas V auquel il avait prédit la tiare, Jean travaillait à la réforme de son

ordre ; disciple de saint Bernardin de Sienne, Jean de Capistran,

visiteur ou vicaire général, s’occupa de la réforme des conventuels et de

l'extension de l'observance, en Italie et en France. « Plus qu'aucun autre

il dilata et accrut, non seulement le premier ordre de Saint-François, mais

encore le second et le troisième. » Il fonda ou réforma un grand nombre de

monastères du second ordre, y mettant en vigueur la première règle de sainte

Claire. Il propagea le tiers-ordre qu’il défendit par le Defensorium

tertii ordinis a sancto Francisco instituti. Il fut envoyé en Allemagne où

il fut chargé d'étendre et de gouverner l'Ordre.

L’empereur Frédéric III et son frère Albert, duc

d'Autriche, demandèrent Jean de Capistran à Nicolas V, pour combattre les

hussites et rétablir la concorde parmi les princes allemands. L’ambassade,

conduite par Æneas Sylvius Piccolomini, futur Pie II, eut un plein succès. Jean

de Capistran, nonce apostolique et inquisiteur, choisit douze compagnons, les

fit pèleriner à Assise et, à pied, ils gagnèrent l’Allemagne dans le

recueillement, un âne portant leurs bagages. Près de Trévise, comme le batelier

leur refusait le passage du Siliano parce qu'ils n'avaient pas d'argent, Jean

étendit sur le fleuve le manteau de saint Bernardin : les eaux se

divisèrent pour laisser passer les religieux, puis se rejoignirent. On leur fit

un triomphe en Lombardie ; en Allemagne, des villes entières se portèrent

à leur rencontre, recevant Jean comme l'envoyé de Dieu. Après quelques jours à

Neustadt, près de la cour, il partit pour Vienne ; Pie II fit ce

portrait : « Il était petit de taille, avancé en âge (65 ans),

desséché, amaigri, épuisé, n'ayant que la peau et les os, et néanmoins toujours

gai et infatigable au travail. Il prêchait tous les jours, traitait les

questions les plus profondes, plaisait aux simples comme aux savants ; il

avait journellement vingt et trente mille auditeurs ; il prêchait en latin

et un interprète traduisait son discours. »

Jean prêcha en Carinthie, en Styrie, en Autriche, en

Bohême, en Moravie, en Silésie, en Bavière, en Thuringe, en Saxe, en Franconie,

en Pologne, en Transylvanie, en Moldavie, en Valachie et dans d'autres

provinces, accomplissant des prodiges, des guérisons et quelques résurrections.

Dans toutes les villes où il prêchait, il faisait apporter les tableaux

obscènes, les cartes, les dés, les faux cheveux ou autres vaines parures, et

les livrait aux flammes, en présence de la foule. Cette exécution solennelle,

l'Incendie du château du diable, introduite par saint Bernardin, était

continuée par tous ses disciples. Un prêtre envieux qui s'était avisé de blâmer

Jean, mourut la nuit suivante. Jean de Capistran envoya plusieurs de ses religieux

en Prusse et en d'autres provinces où il ne pouvait aller lui-même ; de

toutes parts ou réclamait sa présence, on faisait appel à ses conseils.

Après la prise de Constantinople[9], les Turcs menaçaient la Hongrie. A la diète

de Neustadt (2 février 1455) Jean fit approuver une croisade que la mort de

Nicolas V ajourna d’un an ; Calixte III invita les princes chrétiens à

prendre les armes. Jean entra triomphalement en Hongrie ; au milieu de 1455, à

la diète de Bude, il dissipa toutes les hésitations et enthousiasma tous les

cœurs puis il prêcha en Hongrie pour la croisade dont Jean Corvin Hunyade[10] fut nommé généralissime. Le 14 février

1456, à Bude, Jean reçut la croix des mains du cardinal légat.

Les Turcs, par terre et par mer, s'avançaient vers

Belgrade, forteresse de la frontière hongroise, ceinte des eaux de la Save et

du Danube. Jean de Capistran se hâta d'appeler les croisés sous les armes, fit

préparer quelques barques avec des vivres, et, accompagné de quelques

franciscains, avec un petit nombre de croisés, descendit le Danube vers

Belgrade. A Peterwardein, comme il célébrait la messe, tomba du ciel une flèche

où étaient écrits en lettres d'or : « Jean, ne crains pas, poursuis

avec assurance ce que tu as commencé, car par la vertu de mon nom et de la

sainte croix tu remporteras la victoire sur les Turcs. » Il imposa la

croix à ceux qui ne l’avaient pas encore, en fit tous les ornements sacerdotaux

et ordonna de fabriquer un étendard où l’on mit la croix et la figure de saint

Bernardin. Entré à Belgrade le 2 juillet, alors fête de la Visitation, il

trouva les habitants pleins de joie, ne redoutant plus l’attaque des Turcs, du

moment que Jean de Capistran était dans leurs murs. Le quatrième jour, la

ville fut investie par les infidèles. Déterminé à chercher du secours, Jean

célébra la messe, adressa aux croisés une exhortation pour les animer au

courage et à la résistance. De Peterwardein, il écrivit à Hunyade, retiré dans

un de ses châteaux, pour lui annoncer le grand péril et le supplier de lui

venir en aide, pour l'amour de Dieu, pour l'honneur du nom chrétien, et pour

son propre honneur. Hunyade réunit tous les croisés à Semlin, avec quelques

vaisseaux pour forcer le blocus et ravitailler la ville.

Jean écrivit des lettres et députa ses religieux pour

inviter les prélats et les barons à venir conjurer le péril. Les croisés

affluèrent près de Jean de Capistran qui ne se donna plus le temps de manger ni

de dormir, tout entier à la rupture du blocus. Debout sur le rivage, tenant en

main l'étendard sacré, il ne cessait d'invoquer le nom de Jésus. Vaincus sur le

fleuve, les infidèles redoublaient leurs efforts par terre : pendant les

onze jours qui suivirent la victoire navale, Jean resta nuit et jour au milieu

des croisés.

Les Turcs se décidèrent à donner un assaut général et

Jean Hunyade vint pendant la nuit dire à Capistran : « Mon Père, nous

allons infailliblement succomber ! - Ne craignez point, illustre seigneur, lui répondit

Jean de Capistran, Dieu est puissant ; il peut avec des faibles

instruments briser la force des Turcs, défendre la ville et confondre nos

ennemis. Et comme Hunyade répliquait qu'il considérait la citadelle comme

perdue : Ne craignez point, lui dit Jean de Capistran, la

citadelle sera à nous, nous défendons la cause de Dieu et le nom du Christ, je

suis certain que Dieu fera triompher sa cause. »

Il choisit quatre mille croisés parmi les plus forts,

les plus courageux et les plus fidèles, les conduisit dans la citadelle où il

leur ordonna d'invoquer le nom de Jésus. Pendant la soirée et la nuit, on

résista : les Turcs prirent la première enceinte ; un combat acharné

s'engagea près du pont-levis de la seconde enceinte. Les croisés jetèrent des

broussailles enflammées sur les assaillants qui se retirèrent en criant :

« Retirons-nous, car le Dieu des chrétiens combat pour eux. » Au

jour, on vit dans les fossés de nombreux cadavres turcs, alors que seulement

soixante chrétiens étaient morts. Quelques jours plus tard, précédé de son

étendard, Jean de Capistran sortit de la ville pour un nouveau

combat ; les chrétiens acclamaient le nom de Jésus en lançant leurs

flèches et les infidèles terrifiés étaient renversés de leurs chevaux ou

prenaient la fuite. La formidable armée du Croissant fut taillée en pièces et

laissa, dit-on, quarante mille morts sur le terrain ; Mahomet II lui-même, qui

se faisait appeler la terreur de l’univers, blessé d’une flèche, fut

obligé de fuir (14 juillet 1456).

A l'annonce de cette victoire, le pape Calixte III

institua la fête de la Transfiguration. Quelques semaines plus tard, Hunyade

mourait entre les bras de Jean de Capistran qui, brisé par l'âge et les

fatigues, dévoré par une fièvre continuelle, voyait avec calme approcher la

mort ; au couvent de Vilak, près de Sirmium il reçut les derniers

sacrements avec abondance de larmes, puis, étendu sur la terre nue, il

s'endormit paisiblement dans le Seigneur, âgé de soixante et onze ans (23

octobre 1456).

Le corps de Jean de Capistran fut enseveli dans

l'église du couvent de Vilak où les peuples vinrent en foule vénérer son

tombeau, obtenant par son intercession d'innombrables guérisons et plusieurs

résurrections. Les Turcs s'étant emparés de Belgrade (1521), prirent le château

fort de Vilak et ruinèrent le couvent des franciscains. On ne sut plus dès lors

ce qu'était devenue la précieuse dépouille de Jean de Capistran que d’anciennes

archives franciscaines de Bulgarie, découvertes en 1874, disent avoir été

vendue par les Turcs à un riche seigneur qui la donna à une communauté de

basiliens schismatiques. D'après cette version, le corps du saint, préservé de

toute corruption et revêtu de l'habit franciscain, se trouverait à Bistriz en

Roumanie.

Des Vies de saint Jean de Capistran furent

écrites par trois de ses disciples : Christophe de Varèse, Jérôme d’Uldine et

Nicolas de Fara. Dès 1515, Léon X permit à la ville de Capistran et à tout le

diocèse de Sulmone de célébrer, avec une messe et un office solennels, la fête

de Jean qu'on appelait « le champion du saint Nom de Jésus, le chef des

armées catholiques contre les infidèles. » Grégoire XV étendit cette

permission à toutes les familles franciscaines. Cependant, malgré les nombreux

miracles et les nombreuses requêtes, son procès de canonisation ne commença

qu’en 1662 ; il fut canonisé par Alexandre VII, le 16 octobre 1690, et la bulle

de canonisation fut publiée par Benoît XIII, en 1724. Son office a été étendu à

l'Église universelle par Léon XIII (1885). Sa fête était célébrée le 23

octobre, jour anniversaire de sa mort, jusqu’à Léon XIII qui la fixa au 28

mars, mais comme les pays qui lui étaient les plus dévots avaient obtenu de

garder le 23 octobre, Paul VI la rétablit pour tous à cette date.

[1] Louis

I° d’Anjou, second fils de Jean II le Bon (roi de France de 1328 à

1364) et de Bonne de Luxembourg (1315-1349), naquit à Vincennes le 23 juillet

1339. D’abord titré comte de Poitiers, il fut fait comte d’Anjou (1351), comte

du Maine et seigneur de Montpellier ; le comté d’Anjou fut érigé en

duché-pairie en 1360. Il remplaça son père en qualité d'otage à Londres (1360),

mais s'enfuit en octobre 1363, ce qui contraignit Jean II le Bon,

intransigeant sur les questions d'honneur, à revenir se constituer prisonnier

des Anglais. A l’avènement de son frère, Charles V le Sage, il fut nommé

lieutenant du Roi en Languedoc, en Guyenne et en Dauphiné (1364) ; il

reçut aussi le duché de Touraine (1370) contre le comté du Maine. Il remporta

plusieurs succès contre les Anglais en Guyenne et fut nommé régent pendant la

minorité de son neveu Charles VI (1374). Après avoir rempli ses propres

coffres, il se laissa tenter par l'offre de succession du comté de Provence et

du royaume de Naples que lui fit la reine Jeanne, par l'intermédiaire du pape

d’Avignon, Clément VII. Adopté par Jeanne (29 juin 1380), il doit faire face à

Charles de Duras, auquel le pape de Rome, Urbain VI, avait donné l'investiture

de Naples. Ayant passé les Alpes avec une puissante armée, il fut vaincu par

l'habile stratégie de Charles de Duras, et mourut désespéré au château de

Biseglia, près de Bari, le 20 septembre 1384. Sa veuve, Marie de Blois, assura

la régence en Provence jusqu'à la majorité de son fils, Louis II.

[2] Bâtie

sur un éperon rocheux dominant la vallée du Tibre, Pérouse contrôle

une voie de communication, longtemps essentielle, à travers les vallées de

l’Italie centrale. Dès 1353, le cardinal Albornoz, chargé par les papes de

reconstituer l’Etat pontifical, avait entrepris de combattre les autonomies

locales. Tandis que, dans la ville, des luttes civiles opposent les nobles et

les plus riches bourgeois au popolo minuto, à l’extérieur, c’est la guerre

presque constante ; contre les papes, Pérouse doit accepter des alliances

qui l’assujettissent à des tyrans laïcs : Gian-Galeazzo Visconti, puis le

roi Ladislas de Naples. Une seigneurie locale se forme enfin, avec Braccio di

Montone, un aventurier ombrien ; mais il est battu et tué à l’Aquila par

les forces conjuguées du Pape et du roi de Naples (1424). Une oligarchie

nobiliaire maintient une relative indépendance au cours de la période suivante,

mais non la paix : deux familles, les Oddi et les Baglioni, se disputent

le pouvoir avec une véritable férocité.

[3] Ladislas (ou

Lancelot) le Magnanime, né en 1376, fils de Charles III de Duras,

fut roi de Naples de 1386 à 1414. Il régna d'abord sous la régence de sa mère,

et dut défendre sa couronne contre Louis II d'Anjou ; ce ne fut qu'en 1399

qu'il resta enfin seul maître du royaume. Très ambitieux, il étendit ses

prétentions sur toute l'Italie et chercha même à obtenir la couronne impériale.

Il réussit à prendre Rome et les villes voisines (1408) mais se heurta à

l'antipape Jean XXIII et aux Florentins qui firent appel à Louis II d'Anjou.

Vaincu à Rocca Secca (1411), il parvint à rétablir sa position et songeait de

nouveau à dominer l’Italie lorsqu'il mourut à Naples, le 6 août 1414. Sa sœur,

Jeanne II, lui succéda.

[4] Jacques

de la Marche, né en 1394, à Monteprandone (Marches), reçut l’habit à l'Alverne,

des mains de saint Bernardin de Sienne avec qui il entretient une grande amitié

qui les unit dans la luttes pour l'Observance franciscaine, la dévotion au nom

de Jésus et les hauts intérêts de l'Église en Italie et en Europe centrale.

Ordonné prêtre à San Miniato de Florence (1422) il s’emploie à la prédication.

Martin V lui concède l'autorisation de prêcher contre les hérétiques par toute

l'Italie (11 octobre 1426). En 1430, le chapitre général d'Assise le met à la

disposition d'Eugène IV. En 1431, il prêche à Raguse. Le l° avril 1432, nommé

commissaire général de Bosnie, il déploie la plus grande activité dans ce pays.

Il est nommé inquisiteur en Hongrie et en Autriche (22 avril 1436). Après avoir

assisté aux réunions conciliaires de Ferrare, il retourne le (1° décembre 1438)

en Hongrie. Le 3 janvier 1440, il revient en Italie, rencontre Eugène IV à

Florence et prêche ensuite à Padoue. Après avoir tenté en vain de se rendre

dans le Proche-Orient et en Terre Sainte, il se livre à la prédication dans les

Marches, et commence en Italie un apostolat des plus extraordinaires, qui dure

trente ans. En 1444, il rencontre au lac Trasimène saint Bernardin, au terme de

sa vie, et saint Jean de Capistran. En 1457, Calliste III l'envoie de nouveau

en Hongrie comme inquisiteur, mais il doit bientôt quitter ce pays, à cause des

rigueurs du climat. ll reprend ses courses apostoliques, particulièrement en

Italie centrale. En 1475, Sixte IV l’envoie à Naples où il meurt le 28 novembre

1476. Il a été canonisé par Benoît XIII en 1726.

[5] Bernardin

de Sienne : voir au 20 mai. Bernardin Albizeschi, né le 8 septembre 1380,

à Massa Marittima (Maremme toscane), entra chez les Frères Mineurs (8 septembre

1402) et fit la plus grande partie de son noviciat, près de Sienne, au couvent

de Colombaio. Ordonné prêtre, le 7 septembre 1404, il se consacra à la

prédication où il se révéla un orateur de grand talent et plein d’originalité.

Pendant vingt-cinq ans, il parcourut toute l’Italie et répandit la dévotion au

saint Nom de Jésus dont il fit peindre partout le monogramme I H S (Jésus

Sauveur des hommes). Il mourut à Aquila le 20 mai 1444 et fut canonisé le 24

mai 1450.

[6] Le

bienheureux Jean Colombini, riche marchand siennois, né en 1304, fréquenta

assidûment l'hôpital de Santa Maria della Scala ; au contact des malades,

il s'éprit de la pauvreté. Les hardes de mendiant dont il s'affubla le firent

traiter de fou. En dépit des quolibets qu'on lui prodiguait, il se livra à la

méditation et à la prière avec quelques compagnons durant sept ans ; puis

il annonça le règne de Dieu : « Loué soit Jésus-Christ ! Vive

Jésus ! » tel était son mot d'ordre. Il pratiqua la vie apostolique

et ne parla que de paix en une contrée désolée par les rivalités politiques.

Ses disciples se réunirent sous le nom pauvres de Jésus-Christ, de clercs de

Saint-Jérôme ou, plus communément, de Jésuates (1364). Frères lais, les

Jésuates suivaient la règle de Saint-Augustin et étaient voués au service des

malades ; ils furent approuvés par Urbain V (1367), et leurs constitutions

furent approuvées par Eugène IV (1426) ; Pie V les assimila aux ordres

mendiants (1567) et Paul V les autorisa à recevoir la prêtrise. Il y eut aussi

une congrégation de femmes. On ne sait pas exactement la cause pour laquelle

les Siennois chassèrent de leurs murs Colombini et ses compagnons. Des envieux

les confondirent avec les fraticelles, avec lesquels ils n'avaient aucun

rapport. La congrégation fut supprimée en 1668 par Clément IX. Jean Colombini

exerça une influence profonde sur ses contemporains. Il mourut près de Sienne,

le 31 juillet 1367.

[7] Ce concile,

convoqué par le pape Eugène IV à Bâle (25 sessions du 23 juillet 1431 au 7 mai

1437), transféré à Ferrare (18 septembre 1437), puis de là à Florence (16

janvier 1439). Les Pères confirmèrent l’union avec les Grecs (6 juillet 1439),

avec les Arméniens (22 novembre 1439), avec les Jacobites (4 février 1442). Le

25 avril 1442, le concile fut transféré à Rome.

[8] Depuis

1277 où l’archevêque de Milan, Ottone Visconti, a renversé les Torriani, la

famille Visconti a confisqué la seigneurie à son profit et la garde cent

soixante-dix ans, à part un bref retour des Torriani de 1302 à 1309, et

quelques troubles au début du XV° siècle. Pour se maintenir, ils usent de

toutes les armes de la violence et de la ruse, contentant le peuple par des

grands travaux et des conquêtes qui stimulent la vie économique. Une bonne

armée de mercenaires, une diplomatie habile et de saines finances leur

permettent de dominer toute la Lombardie et d’y étouffer les autonomies

locales. leur Etat s’étend des Alpes à Bologne et d’Alexandrie à Bellune. Jean

Galéas Visconti devient duc de Milan (1395), puis duc de Lombardie, par

concession impériale. Après sa mort, des condottieri se disputent

l’héritage que parvient à ressaisir Philippe-Marie Visconti (1412-1447), en

butte aux ambitions de son gendre, François Sforza. En 1447, s’installe une

éphémère république que la force des armes et l’alliance florentine permettent

à François Sforza de renverser pour restaurer le duché qui connaît alors une

réelle prospérité.

[9] A

son avènement (1451), Mahomet II décida de faire de Constantinople sa

capitale. Le dernier empereur grec, Constantin XI, ne pouvait espérer aucun

secours de l’Occident, en dehors d’un petit contingent génois ; il choisit

cependant de résister à la formidable armée turque, vingt fois plus nombreuse

que ses troupes. Après une défense désespérée qui dura sept semaines, la ville

fut prise grâce à l’artillerie de Mahomet II, et Constantin, ne voulant pas

survivre à l’Empire, se fit tuer dans la mêlée.

[10] Jean

Corvin Hunyade (1387-1456), voïvode de Transylvanie (1440), se battit

contre les Turcs à Belgrade (1440), à Maros-Szent-Imre (1441) et aux Portes de

Fer (1442). Régent de Hongrie durant la minorité de Ladislas V (1446-53), il

fut battu à Kosovo, après avoir contenu durant trois jours l'armée ottomane qui

était quatre fois plus nombreuse que la sienne (1448) ; il détruisit

l'armée turque de Firus Bey près de Szendrö (1454). A la majorité de Ladislas

V, il fut nommé capitaine général.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/23.php

St Jean de Capistran, confesseur

Mort le 23 octobre 1456. Inquisiteur sous plusieurs papes, combattant les hérésies et les Turcs. Canonisé en 1690 par Alexandre VIII. Sa fête fut inscrite au calendrier par Léon XIII sous le rite semi-double en 1890. Le 1er avril 1984 Jean-Paul II l’a nommé patron des aumôniers militaires du monde entier.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Jean y naquit à Capistran, au pays des Pélignes. Envoyé à Pérouse pour y faire ses études il fit de si grands progrès dans la doctrine chrétienne et les arts libéraux que Ladislas, roi de Naples, lui confia le gouvernement de plusieurs villes, en considération de sa connaissance du droit. Tandis que saintement occupé de la chose publique, il s’applique à apaiser les troubles et à rétablir la tranquillité, il est fait prisonnier et jeté dans les fers. Miraculeusement délivré, il fait profession de la règle de saint François d’Assise, parmi les frères Mineurs. Dans l’étude des divines Écritures il eut pour maître saint Bernardin de Sienne, dont il imita excellemment les vertus, zélé comme lui à propager le culte du nom de Jésus et de la Mère de Dieu. Il refusa l’évêché d’Aquila ; il se distingua par l’austérité de sa vie et par les nombreux écrits qu’il publia pour la réforme des mœurs.

Cinquième leçon. Tout appliqué à la prédication de la parole de Dieu, il parcourut l’Italie presqu’entière, et dans ce ministère, par la force de ses discours et le grand nombre de ses miracles, il ramena dans la voie du salut des âmes innombrables. Martin V l’établit inquisiteur pour l’extinction de la secte des Fratricelles. Institué inquisiteur général en Italie contre les Juifs et les Sarrasins par Nicolas V, il en convertit un grand nombre à la foi du Christ. Il fit en Orient beaucoup d’excellents établissements, et dans le concile de Florence, où il brilla comme un soleil par sa doctrine, il réconcilia les Arméniens à l’Église catholique. Le même Pontife, sur la demande de l’empereur Frédéric III, l’envoya en Allemagne en qualité de nonce du Siège apostolique, pour ramener les hérétiques à la foi catholique et les princes à la concorde. Dans ce pays et en d’autres provinces, par un ministère de six années, il travailla merveilleusement à la gloire de Dieu, et ramena dans le sein de l’Église, par sa doctrine et ses miracles, une multitude innombrable de Hussites, d’Adamites, de Thaborites et de Juifs.

Sixième leçon. Callixte III, pressé par ses instances, ayant décrété la croisade, Jean parcourut la Pannonie et d’autres provinces, et, soit par sa parole, soit par ses lettres, anima tellement les princes à la guerre sainte, qu’en peu de temps soixante-dix mille chrétiens furent enrôlés. C’est principalement à ses conseils et à son courage que l’on dut la victoire de Belgrade, où cent vingt mille Turcs furent taillés en pièces ou mis en fuite. L’annonce de cette victoire étant parvenue à Rome au huitième des ides d’août, le même Callixte consacra à perpétuité la mémoire de ce jour par l’institution de la solennité de la Transfiguration de notre Seigneur. Atteint d’une maladie mortelle, et transporté à Willech, Jean y fut visité par plusieurs princes qu’il exhorta à défendre la religion ; il rendit saintement son âme à Dieu, l’an du salut quatorze cent cinquante-six. Dieu fit éclater sa gloire après sa mort par beaucoup de miracles. Alexandre VIII, les ayant régulièrement approuvés, inscrivit Jean au nombre des Saints en l’année mil six cent quatre-vingt-dix. Léon XIII, deux siècles après sa canonisation, étendit à toute l’Église l’Office et la Messe de sa Fête.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Luc. Cap. 9, 1-6.

En ce temps-là : Jésus, ayant assemblé les douze Apôtres, leur donna puissance et autorité sur tous les démons, et le pouvoir de guérir les maladies. Et le reste.

Homélie de S. Bonaventure, Évêque.

Septième leçon. Les Apôtres ont reçu ce nom pour établir leur autorité. Le nom d’Apôtre, en effet, signifie envoyé. Ils avaient été envoyés pour prêcher, selon cette parole : « Le Christ ne m’a pas envoyé pour baptiser, mais pour prêcher l’Évangile ». Ils furent envoyés pour prêcher non une chose de peu d’importance, mais une grande chose, à savoir le royaume de Dieu, ce qui peut s’entendre de la doctrine de la vérité, selon cette parole : « Le royaume de Dieu vous sera ôté, et il sera donné à un peuple qui en produira les fruits ». On peut aussi l’entendre de la grâce de l’Esprit-Saint, selon cette parole : « Le royaume de Dieu n’est pas la nourriture et le breuvage, mais il est justice, paix et joie dans l’Esprit-Saint. » Et plus bas : « Voilà que le royaume de Dieu est au dedans de vous. » On peut encore l’entendre de la gloire éternelle, selon cette autre parole : « En vérité, je vous le dis, si l’on ne renaît de l’eau et de l’Esprit-Saint, on ne peut entrer dans le royaume de Dieu ».

Huitième leçon. En toutes ces manières les Apôtres ont été envoyés pour prêcher le royaume de Dieu, c’est-à-dire la vraie doctrine, la grâce divine et la gloire éternelle. Comme il leur avait accordé. le pouvoir des guérisons pour autoriser leur prédication, il ajoute : Je vous envoie guérir les malades, et ainsi il les envoya prêcher, avec le pouvoir de confirmer la vérité de leur doctrine, selon cette parole : « Et eux, étant partis, prêchèrent partout, le Seigneur agissant avec eux, et confirmant leur parole par les prodiges qui l’accompagnaient. » Le signe de la mission spirituelle qui leur est donnée pour la prédication est donc la guérison des auditeurs, de la maladie des vices.

Neuvième leçon. Or il y a trois marques évidentes par

lesquelles le prédicateur prouve qu’il est envoyé par le Seigneur pour annoncer

l’Évangile. La première est l’autorité de celui qui l’envoie, telle que celle

du Pontife, et surtout du souverain Pontife qui tient la place de Pierre et de

Jésus-Christ lui-même, d’où il suit que celui qu’il envoie est envoyé par le

Christ. La seconde est le zèle des âmes dans la personne qui est envoyée,

lorsque cette personne cherche principalement l’honneur de Dieu et le salut des

âmes. La troisième est le fruit spirituel et la conversion des auditeurs. Par

la première de ces marques, ils sont les envoyés du Père ; par la seconde, ceux

du Fils ; par la troisième, ceux du Saint-Esprit. Au sujet de la première, il

est dit : « Au lieu de vos pères, des fils vous sont nés. » Au sujet de la

seconde : « Nous ne nous prêchons pas nous-même, mais Jésus-Christ notre

Seigneur. » Au sujet de la troisième : « Je vous ai établis, pour que vous

ailiez, et rapportiez du fruit, et que votre fruit demeure ». Celui qui reçoit

une telle mission peut dire cette autre parole : « L’esprit du Seigneur est sur

moi, parce qu’il m’a donné son onction ».

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Plus l’Église semble approcher du terme de ses

destinées, plus aussi l’on dirait qu’elle aime à s’enrichir de fêtes nouvelles

rappelant le glorieux passé. C’est qu’en tout temps du reste, un des buis du

Cycle sacre est de maintenir en nous le souvenir des bienfaits du Seigneur.

Ayez mémoire des anciens jours, considérez l’histoire des générations

successives, disait déjà Dieu sous l’alliance du Sinaï [1] ; et c’était une loi

en Jacob, que les pères rissent connaître à leurs descendants, pour

qu’eux-mêmes les transmissent à la postérité, les récits antiques [2]. Plus

qu’Israël qu’elle a remplacé, l’Église a ses annales remplies des

manifestations de la puissance de l’Époux ; mieux que la descendance de Juda,

les fils de la nouvelle Sion peuvent dire, en contemplant la série des siècles

écoulés : Vous êtes mon Roi, vous êtes mon Dieu, vous qui toujours sauvez Jacob

[3] !

Tandis que s’achevait en Orient la défaite des

Iconoclastes, une guerre plus terrible, où l’Occident devait lutter lui-même

pour la civilisation et pour l’Homme-Dieu, commençait à peine.

Comme un torrent soudain grossi, l’Islam avait

précipité de l’Asie jusqu’au centre des Gaules ses flots impurs ; pied à pied,

durant mille années, il allait disputer le sol occupé par les races latines au

Christ et à son Église. Les glorieuses expéditions des XIIe et XIIIe siècles,

en l’attaquant au centre même de sa puissance, ne firent que l’immobiliser un

temps. Sauf sur la terre des Espagnes, où le combat ne devait finir qu’avec le

triomphe absolu de la Croix, on vit les princes, oublieux des traditions de

Charlemagne et de saint Louis, délaisser pour les conflits de leurs ambitions

privées la guerre sainte, et bientôt le Croissant, défiant à nouveau la

chrétienté, reprendre ses projets de conquête universelle.

En 1453, Byzance, la capitale de l’empire d’Orient,

tombait sous l’assaut des janissaires turcs ; trois ans après, Mahomet II son

vainqueur investissait Belgrade, le boulevard de l’empire d’Occident. Il eût

semblé que l’Europe entière ne pouvait manquer d’accourir au secours de la

place assiégée. Car cette dernière digue forcée, c’était la dévastation

immédiate pour la Hongrie, l’Autriche et l’Italie ; pour tous les peuples du

septentrion et du couchant, c’était à bref délai la servitude de mort où gisait

cet Orient d’où nous est venue la vie, l’irrémédiable stérilité du sol et des

intelligences dont la Grèce, si brillante autrefois, reste encore aujourd’hui

frappée.

Or toutefois, l’imminence du danger n’avait eu pour

résultat que d’accentuer la division lamentable qui livrait le monde chrétien à

la merci de quelques milliers d’infidèles. On eût dit que la perte d’autrui dût

être pour plusieurs une compensation à leur propre ruine ; d’autant qu’à cette

ruine plus d’un ne désespérait pas d’obtenir délai ou dédommagement, au prix de

la désertion de son poste de combat. Seule, à rencontre de ces égoïsmes, au

milieu des perfidies qui se tramaient dans l’ombre ou déjà s’affichaient

publiquement, la papauté ne s’abandonna pas. Vraiment catholique dans ses

pensées, dans ses travaux, dans ses angoisses comme dans ses joies et ses

triomphes, elle prit en mains la cause commune trahie par les rois. Éconduite

dans ses appels aux puissants, elle se tourna vers les humbles, et plus

confiante dans sa prière au Dieu des armées que dans la science des combats,

recruta parmi eux les soldats de la délivrance.

C’est alors que le héros de ce jour, Jean de

Capistran, depuis longtemps déjà redoutable à l’enfer, consomma du même coup sa

gloire et sa sainteté. A la tête d’autres pauvres de bonne volonté, paysans,

inconnus, rassemblés par lui et ses Frères de l’Observance, le pauvre du Christ

ne désespéra pas de triompher de l’armée la plus forte, la mieux commandée

qu’on eût vue depuis longtemps sous le ciel. Une première fois, le 14 juillet

1456, rompant les lignes ottomanes en la compagnie de Jean Hunyade, le seul des

nobles hongrois qui eût voulu partager son sort, il s’était jeté dans Belgrade

et l’avait ravitaillée. Huit jours plus tard, le 22 juillet, ne souffrant pas

de s’en tenir à la défensive, sous les yeux d’Hunyade stupéfié par cette

stratégie nouvelle, il lançait sur les retranchements ennemis sa troupe armée

de fléaux et de fourches, ne lui donnant pour consigne que de crier le nom de

Jésus à tous les échos C’était le mot d’ordre de victoire que Jean de Capistran

avait hérité de Bernardin de Sienne son maître. Que l’adversaire mette sa

confiance dans les chevaux et les chars, disait le Psaume ; pour nous, nous

invoquerons le Nom du Seigneur [4]. Et en effet, le Nom toujours saint et

terrible [5] sauvait encore son peuple. Au soir de cette mémorable journée,

vingt-quatre mille Turcs jonchaient le sol de leurs cadavres ; trois cents

canons, toutes les armes, toutes les richesses des infidèles étaient aux mains

des chrétiens ; Mahomet II, blessé, précipitant sa fuite, allait au loin cacher

sa honte et les débris de son armée.

Ce fut le 6 août que parvint à Rome la nouvelle d’une

victoire qui rappelait celle de Gédéon sur Madian [6]. Le Souverain Pontife,

Calliste III, statua que désormais toute l’Église fêterait ce jour-là

solennellement la glorieuse Transfiguration du Seigneur. Car en ce qui était

des soldats de la Croix, ce n’était pas leur glaive qui avait délivré la terre,

ce n’était pas leur bras qui les avait sauvés, mais bien votre droite et la

puissance de votre bras à vous, ô Dieu, et le resplendissement de votre visage,

parce que vous vous étiez complu en eux [7], comme au Thabor en votre Fils

bien-aimé [8].

Le Seigneur est avec vous, ô le plus fort des hommes !

Allez dans cette force qui est la vôtre, et délivrez Israël, et triomphez de

Madian : sachez que c’est moi qui vous ai envoyé [9]. Ainsi l’Ange du Seigneur

saluait Gédéon, quand il le choisissait pour ses hautes destinées parmi les

moindres de son peuple [10]. Ainsi pouvons-nous, la victoire remportée, vous

saluer à notre tour, ô fils de François d’Assise, en vous priant de nous aider

toujours. L’ennemi que vous avez vaincu sur les champs de bataille n’est plus à

redouter pour notre Occident ; le péril est bien plutôt où Moïse le signalait

pour son peuple après la délivrance, quand il disait : Prenez garde d’oublier

le Seigneur votre Dieu, de peur qu’après avoir écarté la famine, bâti de belles

maisons, multiplié vos troupeaux, votre argent et votre or, goûté l’abondance

de toutes choses, votre cœur ne s’élève et ne se souvienne plus de Celui qui

vous a sauvés de la servitude [11]. Si, en effet, le Turc l’eût emporté, dans

la lutte dont vous fûtes le héros, où serait cette civilisation dont nous

sommes si fiers ? Après vous, plus d’une fois, l’Église dut assumer sur elle à

nouveau l’œuvre de défense sociale que les chefs des nations ne comprenaient

plus. Puisse la reconnaissance qui lui est due préserver les fils de la Mère

commune de ce mal de l’oubli qui est le fléau de la génération présente ! Aussi

remercions-nous le ciel du grand souvenir dont resplendit par vous en ce jour

le Cycle sacré, mémorial des bontés du Seigneur et des hauts faits des Saints.

Faites qu’en la guerre dont chacun de nous reste le champ de bataille, le nom

de Jésus ne cesse jamais de tenir en échec le démon, le monde et la chair ;

faites que sa Croix soit notre étendard, et que par elle nous arrivions, en

mourant à nous-mêmes, au triomphe de sa résurrection.

[1] Deut. XXXII, 7.

[2] Psalm. LXXVII, 5.

[3] Psalm. XLIII, 5.

[4] Psalm. XIX, 8.

[5] Psalm. CX, 9.

[6] Judic. VII.

[7] Psalm. XLIII, 4.

[8] Matth. XVII, 5.

[9] Judic. VI.

[10] Ibid. 15.

[11] Deut. VIII, 11-14.

Durant cette période quadragésimale, nos ancêtres,

jusqu’au XVIIe siècle, avaient été très sobres dans la célébration de fêtes de

saints ; et cela, pour vaquer dans un plus grand recueillement, et sous la

direction éclairée de la liturgie, aux exercices de pénitence et de

purification qui nous doivent disposer à célébrer la solennité pascale.

L’attièdissement de la foi en ces derniers siècles a conseillé à l’Église

d’adoucir beaucoup l’antique discipline quadragésimale, pour l’adapter à la

faiblesse des esprits modernes ; il en est résulté que ce saint temps, ne

différant plus guère du reste de l’année, sa liturgie elle-même a été moins

comprise et est passée au second plan.

Presque tous les jours qui, dans le calendrier romain

de saint Pie V, étaient demeurés encore libres d’offices de saints, furent donc

postérieurement occupés par des offices nouveaux, beaux sans doute, et

importants au point de vue de l’histoire et de la théologie, mais qui ont

toutefois l’inconvénient d’avoir brisé, bien plus, d’avoir presque détruit ce

cycle merveilleux, si ancien et si profondément théologique, qu’est la liturgie

du Carême.

Nous sommes bien loin de l’âge d’or où la préparation

à Pâques exigeait la fermeture des théâtres et des tribunaux ; alors tout le

monde romain, à commencer par le Basileus de Byzance, se couvrait de cilice et

de cendre, et le jeûne rigoureux, jusqu’au coucher du soleil, était si

universel qu’il semblait être devenu, plutôt qu’un acte particulier de

dévotion, une des formes essentielles du culte du monde romain et chrétien.

Aujourd’hui, pour les tièdes fidèles de notre siècle,

la sainte Quarantaine ne comporte plus, pour ainsi dire, aucun changement dans

la vie ordinaire de l’année ; aussi la liturgie sacrée qui, en pratique, a

toujours été, en tous temps, un reflet exact de l’esprit chrétien de l’époque,

se borne-t-elle elle aussi, pendant la plus grande partie du Carême, à ajouter

à l’office divin en l’honneur du Saint du jour une commémoraison spéciale de la

férié courante.

Mais un mouvement de saine réforme, en ces dernières

années, est parti de Rome, et l’on espère qu’il produira des fruits abondants

de piété. Pie X, fidèle à son programme de tout restaurer dans le Christ, après

avoir rendu à leur fraîcheur native les mélodies grégoriennes, a voulu

restituer au Psautier son ancienne place dans la prière ecclésiastique. Pour

mieux atteindre ce but, il a allégé le calendrier de quelques fêtes, donnant

une plus large préséance à l’office dominical et férial, en sorte que le

primitif office De tempore a commencé de réapparaître à la lumière dans ses

lignes classiques, comme un antique chef-d’œuvre délivré des adjonctions

postérieures qui le déformaient.

La messe de saint Jean de Capistran (+ 1456),

franciscain, insigne prédicateur de la croisade contre les Turcs, fut instituée

en 1890 par Léon XIII. Son rédacteur s’est laissé profondément impressionner

par la splendide victoire de Belgrade, remportée surtout grâce aux prières et

aux exhortations du Saint. Cette messe est beaucoup plus riche et plus variée

que la précédente en l’honneur de saint Jean Damascène. Elle s’inspire en

grande partie de la vive dévotion professée par le grand Franciscain envers le

saint Nom de Jésus.

Le verset pour l’introït est tiré du cantique

d’Habacuc (III, 18) et fait allusion à la victoire de Belgrade.

La prière a des réminiscences historiques. Les

anciennes croisades contre les infidèles doivent être considérées à ce point de

vue surnaturel où les envisageaient nos pères. Elles représentèrent l’effort

suprême de la chrétienté pour que la force brutale des musulmans n’anéantît pas

la civilisation de l’Évangile. L’âme de cette résistance puissante, longue et

finalement victorieuse à Lépante et à Vienne, fut le pontificat romain qui,

pendant plus de cinq siècles, ne regardant ni aux sacrifices ni aux dépenses,

rassembla en un seul faisceau, sous l’étendard de la Croix, les forces

catholiques de chaque nation et, les dirigeant contre le Croissant, épargna à

l’Europe un grand nombre de guerres intestines, lui assurant en outre le

triomphe sur l’Asie occidentale et sur l’Islam.

La lecture (Sap., X, 10-14) est, en grande partie, la

même que celle du jour précédent, et contient une allusion manifeste aux

persécutions et à la prison endurées par le Saint pour la foi. Mais le Seigneur

descendit avec lui dans le sombre cachot, l’en retira triomphant, et écrasa les

ennemis qui voulaient le fouler aux pieds. Ils étaient ennemis du juste parce

qu’ils étaient aussi ennemis de Dieu ; et c’est pourquoi le Tout-Puissant,

prenant sa défense, jugea et fit triompher Sa cause, selon la parole du

Prophète : Exsurge, Deus, iudica causant tuam : memor esto improperiorum

tuorum, evrum quae ab insipiente sunt tota die.

Relativement à l’observance de la Loi, le judaïsme

authentique ne reconnaissait que deux catégories : celle des descendants

d’Israël qui, en vertu de la circoncision, pouvaient seuls aspirer à la

plénitude des espérances messianiques ; et celle des Gentils, les parias de

Yahweh, qui craignaient le Dieu d’Abraham, se faisaient circoncire, s’obligeant

à observer la loi, mais n’avaient part aux privilèges des Israélites qu’à un

degré inférieur. Dans le verset de psaume suivant, il est fait allusion à cette

distinction entre les prosélytes qui craignent Dieu, et la pure race Israélite

qui a stipulé avec le Seigneur un véritable contrat d’amitié.

Le trait est tiré du magnifique cantique de Moïse

après la défaite de l’armée du Pharaon au passage de la mer Rouge et il

s’adapte fort bien au caractère de la fête de ce jour, qui est comme un écho

annuel du triomphe remporté sur le Croissant sous les murs de Belgrade.

La lecture de l’Évangile (Luc., IX, 1-6) traite des

conditions et des privilèges de l’apostolat chrétien, toutes choses qui

n’appartiennent pas seulement à l’histoire évangélique, mais qui demeurent,

dans l’Église catholique, toujours d’actualité. Il suffit en effet de penser

aux pauvres missionnaires qui étendent le règne de Dieu dans les contrées

inhospitalières de l’Océanie, de l’Afrique et de l’Asie, pour se convaincre que

seul l’esprit de Dieu qui anime, sanctifie et dirige le corps mystique de

l’Église, peut rendre les hommes capables d’un pareil héroïsme.

L’offertoire, où l’on applique à notre Saint l’éloge

de Josué fait par l’Ecclésiastique, chante lui aussi la victoire de Belgrade,

attribuée, plutôt qu’aux armes des combattants, au bras du Dieu invoqué par

Jean.

Autrefois c’était l’Islam qui menaçait la civilisation

chrétienne. Maintenant c’est le judaïsme, le peuple sans patrie, et qui hait

celle des autres, allié comme il l’est avec la franc-maçonnerie. Juifs et

maçons livrent au catholicisme et à l’Europe une guerre d’autant plus rude et

dangereuse qu’elle est plus hypocrite. Contre ce redoutable péril, nous devons

recourir nous aussi aux armes invincibles de la prière ; et puisque il ne nous

est permis de haïr personne, mais qu’il nous est au contraire ordonné d’aimer

tout le monde, même nos ennemis, demandons aujourd’hui la conversion de ces

âmes égarées qui ont déchaîné le cruel fléau de la guerre, et qui, seules, en

ont profité — juifs, bolchevistes, sionistes, francs-maçons, etc., afin que

tous, convertis à la pénitence, Ecclesia... tranquilla devotione laetetur.

Prodige de la droite du Très-Haut ! Pour accomplir les

grandes merveilles, II emploie de préférence des instruments très humbles, les

moins adaptés parfois et les plus méprisés par les hommes, afin que le succès

ne puisse être attribué à la créature, mais au seul Créateur. Ainsi au XVe

siècle, en plein humanisme, quand les puissances chrétiennes elles-mêmes, au

lieu d’écouter la voix du Pasteur suprême et de marcher ensemble contre le

Croissant qui menaçait la liberté du monde civilisé, rivalisaient entre elles

par une politique mensongère. Dieu suscita un humble disciple de saint

François, de peu d’apparence, pauvre et sans moyens, qui ébranla par sa parole

enflammée la moitié de l’Europe et la conduisit en triomphe sous les murs de

Belgrade. Digitus Dei est hic.

Rome chrétienne peut considérer comme un sanctuaire de

saint Jean de Capistran le vieux monastère de Sainte-Marie sur le Capitole,

qui, passé des moines bénédictins aux Mineurs durant le bas moyen âge, fut

sanctifié par la résidence du Saint.

Kath. Pfarrkirche hl. Theresia vom Kinde Jesu

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide dans l’année liturgique

Nous sommes les soldats du Christ.

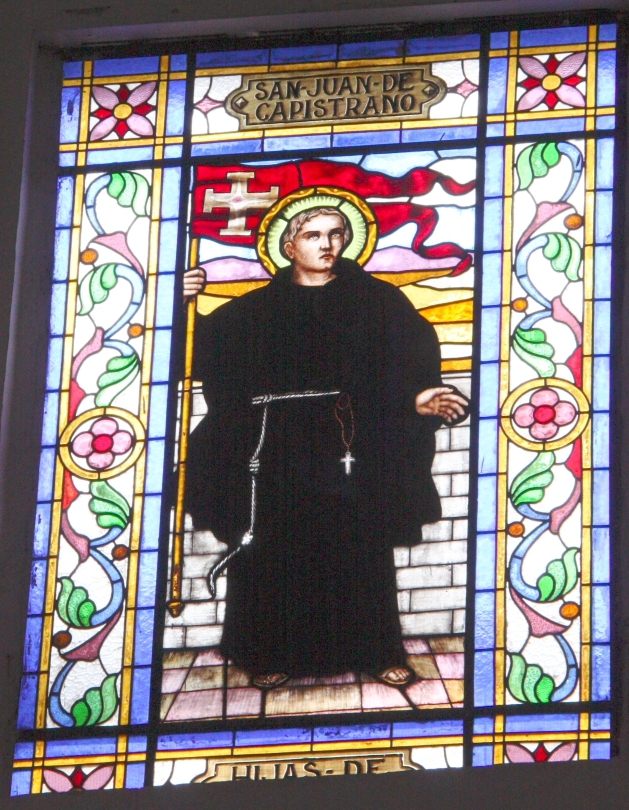

Saint Jean : Jour de mort : 23 octobre 1456. — Tombeau

à Ujlak, à la frontière bosniaque, dans un monastère fondé par lui, mais son

corps fut dérobé par les Turcs et est perdu. Image : On le représente en

franciscain avec une croix rouge sur la poitrine. Vie : Saint Jean de Capistran

compte parmi les plus puissants prédicateurs populaires de tous les temps. «

Cet homme, nous l’avons vu à Nuremberg, âgé de 65 ans, vieux, petit, maigre,

sec, n’ayant plus que les os et la peau, mais joyeux et vaillant à l’ouvrage,

prêchant tous les jours sans relâche et traitant les sujets les plus élevés. »)

Ainsi écrit l’humaniste Hartmann Schedel de Nuremberg, dans sa chronique du

monde. Tout le monde connaît la célèbre victoire que les chrétiens remportèrent

sur les Turcs, près de Belgrade, en 1456. On doit l’attribuer à sa bravoure et

à son zèle.

Pratique : Nous devons nous considérer, aujourd’hui,

comme les soldats du Christ. Sous la conduite de notre saint, nous triompherons

des ennemis. Jadis, c’étaient les Turcs ; ce sont d’autres ennemis,

aujourd’hui, mais l’enfer est toujours derrière eux. La liturgie est une grande

œuvre de paix, mais c’est parce qu’elle fait de l’Église militante une armée

prête au combat. — Nous prenons la messe du Carême avec Mémoire du saint.

2. Quelques traits de sa vie. — Partout où il allait,

il était reçu en procession solennelle par le peuple et le clergé. Les plus

grandes églises ne pouvaient contenir la foule des auditeurs. C’est pourquoi il

était obligé de prêcher en plein air, sur une estrade. A Meissen, il prêcha du

haut d’un toit. Partout, des foules immenses se pressaient à ses sermons. Il

avait parfois, autour de lui, vingt ou trente mille hommes. A Erfurt, il eut,

une fois, 60.000 auditeurs. Un jour, à Vienne, 100.000 personnes attendaient le

commencement de son sermon. Le peuple l’écoutait en pleurant et en gémissant,

bien qu’il ne comprît pas son langage. Il prêchait en latin ; un de ses

compagnons donnait ensuite la traduction en allemand. Bien que le sermon eût

duré deux ou trois heures, le peuple restait encore autant de temps, en plein

air ou dans les rues, malgré la neige et le froid, jusqu’à ce que l’interprète

eût achevé la traduction.

Rien que d’avoir pu voir de loin le « saint » était

une consolation pour le peuple simple et croyant. Il n’était pas rare de voir

les auditeurs grimper aux arbres du voisinage et s’asseoir sur les branches.

Souvent, les branches rompaient sous le poids. Cependant, on n’a jamais entendu

dire qu’il y avait eu des accidents.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/28-03-St-Jean-de-Capistran#nh1

Also known as

Giovanni da Capestrano

Ivan Kapistran

Jan Kapistran

John Capistran

Jovan Kapistran

János Kapisztrán

formerly 28 March

Profile

Son of a German knight,

his father died when

John was still young. The young man studied law at

the University of Perugia,

and worked as a lawyer in Naples, Italy.

Reforming governor of Perugia under King Landislas

of Naples.

When war broke out between Perugia and

the House of Malatesta from Rimini, Italy in 1416,

John tried to broker a peace,

but when the opponents ignored the truce, John became a prisoner

of war.

During his imprisonment,

John came to the decision to change vocations. He had married just

before the war, but the marriage was

never consummated, and with his bride’s permission, it was annulled. He joined

the Franciscans at Perugia on 4 October 1416.

Fellow student with Saint James

of the Marches. Disciple of Saint Bernadine

of Siena. Noted preacher while

still a deacon,

beginning his work in 1420.

Itinerant priest throughout Italy, Germany, Bohemia, Austria, Hungary, Poland,

and Russia, preaching to

tens of thousands. Established communities of Franciscan renewal.

John was reported to heal by

making the Sign

of the Cross over a sick person. Wrote extensively,

mainly against the heresies of

the day.

After the fall of Constantinople,

he preached Crusade against

the Muslim Turks. At age 70 he was commissioned by Pope Callistus

II to lead it, and marched off at the head of 70,000 Christian soldiers.

He won the great battle of Belgrade in

the summer of 1456.

He died in

the field a few months later, but his army delivered Europe from

the Muslims.

Born

1386 at Capistrano, Italy

23

October 1456 at

Villach, Hungary of

natural causes

19

December 1650 by Pope Innocent

X

16

October 1690 by Pope Alexander

VIII

military ordinariate of the Philippines

—

man with a crucifix and lance,

treading a turban underfoot

Franciscan with cross on

his breast and carrying banner of

the cross

Franciscan preaching, angels with rosaries and IHS above

him

Franciscan pointing

to a crucifix he

is holding

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saint

John Capistran, by Mary Helen Allies

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian

Catholic Truth Society

images

e-books

Saint

John Capistran, by Father Vincent

Fitzgerald

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

websites in nederlandse

nettsteder i norsk

Readings

Those who are called to the table of the Lord must

glow with the brightness that comes from the good example of a praiseworthy and

blameless life. They must completely remove from their lives the filth and

uncleanness of vice. Their upright lives must make them like the salt of the

earth for themselves and for the rest of mankind. The brightness of their

wisdom must make them like the light of the world that brings light to others.

They must learn from their eminent teacher, Jesus Christ, what he declared not

only to his apostles and disciples, but also to all the priests and clerics who

were to succeed them, when he said, “You are the salt of the earth. But what is

salt goes flat? How can you restore its flavor? Then it is good for nothing but

to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.” Jesus also said: “You are the light

of the world.” Now a light does not illumine itself, but instead it diffuses

its rays and shines all around upon everything that comes into its view. So it

must be with the glowing lives of upright and holy clerics. By the brightness

of their holiness they must bring light and serenity to all who gaze upon them.

They have been placed here to care for others. Their own lives should be an

example to others, showing how they must live in the house of the Lord. –

from the treatise Mirror of the Clergy by Saint John

of Capistrano

MLA Citation

“Saint John of Capistrano“. CatholicSaints.Info.

23 October 2021. Web. 23 October 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-of-capistrano/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-of-capistrano/

St. John Capistran

Born at Capistrano, in the Diocese of Sulmona, Italy,

1385; died 23 October, 1456. His father had come toNaples in

the train of Louis of Anjou, hence is supposed to have been of French blood,

though some say he was of German origin. His father dying early, John

owed his education to

his mother. She had him at first instructed at home and then sent him to

study law at Perugia,

where he achieved great success under the eminent legist, Pietro de Ubaldis. In

1412 he was appointed governor of Perugia by

Ladislaus, King of Naples,

who then held that city of the Holy

See. As governor he set himself against civic corruption and bribery. War broke

out in 1416 between Perugia and

the Malatesta.

John was sent as ambassador to propose peace to the Malatesta,

who however cast him into prison.

It was during this imprisonment that

he began to think more seriously about hissoul.

He decided eventually to give up the world and become a Franciscan Friar,

owing to a dream he

had in which he saw St.

Francis and was warned by the saint to

enter the Franciscan

Order. John had married a wealthylady of Perugia immediately

before the war broke

out, but as the marriage was

not consummated he obtained adispensation to

enter religion,

which he did 4 October, 1416.

After he had taken his vows he

came under the influence of St.

Bernardine of Siena, who taught him theology:

he had as his fellow-student St.

James of the Marches. He accompanied St.

Bernardine on his preaching tours in order to study his methods, and

in 1420, whilst still in deacon's orders,

was himself permitted to preach. But his apostolic life began in 1425, after he

had received the priesthood.

From this time until his death he laboured ceaselessly for the salvation of souls.

He traversed the whole of Italy;

and so great were the crowds who came to listen to him that he often had to

preach in the public squares. At the time of his preaching all business

stopped. At Brescia on

one occasion he preached to a crowd of one hundred and twenty-six thousand

people, who had come from all the neighbouring provinces. On another occasion

during a mission,

over two thousand sick people were brought to him that he might sign them with

the sign

of the Cross, so great was his fame as a healer of the sick. Like St.

Bernardine of Siena he greatly propagated devotion to

the Holy

Name of Jesus, and, together with that saint,

was accused of heresy because

of this devotion.

While he was thus carrying on his apostolic work, he was actively engaged in

assisting St.

Bernardine in the reform of

the Franciscan

Order. In 1429 John, together with other Observant friars,

was cited to Rome on

the charge of heresy,

and he was chosen by his companions to defend their cause; the friars were

acquitted by the commission of cardinals.

After this, Pope

Martin V conceived the idea of

uniting the Conventual

Friars Minor and the Observants,

and ageneral

chapter of both bodies of Franciscans was

convoked at Assisi in

1430. A union was effected, but it did not last long. The following year

the Observants held

a chapter at Bologna, at which John was the moving spirit. According to

Gonzaga, John was about this time appointed commissary

general of the Observants,

but his namedoes

not appear among the commissaries and vicars in

Holzapfel's list (Manuale Hist. Ord. FF. Min., 624-5) before 1443. But it was

owing to him that St.

Bernardine was appointed vicar-general in

1438. Shortly after this, whilst visiting France he

met St.

Colette, the reformer of

the Second

Franciscan Order or Poor

Clares, with whose efforts he entirely sympathized. He was frequently

employed on embassies by the Holy

See. In 1439 he was sent as legate to Milan and Burgundy,

to oppose the claims of the antipope Felix

V; in 1446 he was on a mission to the King of France;

in 1451 he went at the request of the emperor as Apostolic

nuncio to Austria.

During the period of his nunciature John

visited all parts of the empire, preaching and combatting the heresy of

theHussites;

he also visited Poland at

the request of Casimir IV. In 1454 he was summoned to the Diet at Frankfort,

to assist that assembly in its deliberation concerning a crusade against

the Turks for

the relief of Hungary:

and here, too, he was the leading spirit. When the crusade was

actually in operation John accompanied the famousHunyady throughout

the campaign: he was present at the battle of Belgrade,

and led the left wing of theChristian army

against the Turks.

He was beatified in

1694, and canonized in

1724. He wrote many books, chiefly against the heresies of

his day.

Sources

Three lives written by the saint's companions,

NICHOLAS OF FARA, CHRISTOPHER OF VARESE, and JEROME OF UNDINE, are given by the

Bollandists, Acta SS. X, October; WADDING, Annales, IX-XIII;

GUIRARD, St. Jean de Capistran et son temps (Bourges, 1865);

JACOB, Johannes von Capistrano (Doagh, 1903); ALLIES, Three

Catholic Reformers (London, 1872); PASTOR, History of the Popes, II

(London, 1891); LEO, Lives of the Saints and Blessed of the three Orders

of St. Francis, III (Taunton, 1886).

Hess, Lawrence. "St. John

Capistran." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York:

Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 28 Oct. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08452a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for

New Advent by Paul T. Crowley. In Memoriam, Mrs. Betty McHugh.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. October

1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal

Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08452a.htm

St. John of Capistrano

St. John was born at Capistrano, Italy in 1385, the

son of a former German knight in that city. He studied law at the University of

Perugia and practiced as a lawyer in the courts of Naples. King Ladislas of

Naples appointed him governor of Perugia. During a war with a neighboring town

he was betrayed and imprisoned. Upon his release he entered the Franciscan

community at Perugia in 1416.

He and St. James of the March were fellow students

under St. Bernardine of Siena, who inspired him to institute the devotion to

the holy Name of Jesus and His Mother. John began his brilliant preaching

apostolate with a deacon in 1420. After his ordination he traveled

throughout Italy, Germany, Bohemia, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Russia

preaching penance and establishing numerous communities of Franciscan renewal.

When Mohammed II was threatening Vienna and Rome, St.

John, at the age of seventy, was commissioned by Pope Callistus III to preach

and lead a crusade against the invading Turks. Marching at the head of seventy

thousand Christians, he gained victory in the great battle of Belgrade against

the Turks in 1456. Three months later he died at Illok, Hungary. His feast day

is October 23. He is the patron of jurists.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-john-of-capistrano/

Ein Denkmal für den heiligen St. Johann von Capistran,

gestaltet von Bildhauer Prof. Josef Henselmann. Es steht vor der St. Johann von

Capistran Kirche in München-Bogenhausen in Bayern, Deutschland.

Memorial for St. Johann from Capistran in front of the

St. Johann von Capistran Church in Munich Bogenhausen, Bavaria, Germany.

Created by the sculptor Prof. Josef Henselmann.

ST JOHN OF CAPISTRANO (A.D. 1456)

CAPISTRANO is a little town in the Abruzzi, which of old formed part of the

kingdom of Naples. Here in the fourteenth century a certain free-lance --

whether he was of French or of German origin is disputed -- had settled down

after military service under Louis I and had married an Italian wife. A son,

named John, was born to him in 1386 who was destined to become famous as one of

the great lights of the Franciscan Order. From early youth the boy's talents

made him conspicuous. He studied law at Perugia with such success that in 1412

he was appointed governor of that city and married the daughter of one of the

principal inhabitants. During hostilities between Perugia and the Malatestas he

was imprisoned, and this was the occasion of his resolution to change his way

of life and become a religious. How he got over the difficulty of his marriage

is not altogether clear. But it is said that he rode through Perugia on a

donkey with his face to the tail and with a huge paper hat on his head upon

which all his worst sins were plainly written. He was pelted by the children

and covered with filth, and in this guise presented himself to ask admission

into the noviceship of the Friars Minor. At that date, 1416, he was thirty

years old, and his novice-master seems to have thought that for a man of such

strength of will who had been accustomed to have his own way, a very severe

training was necessary to test the genuineness of his vocation. (He had not yet

even made his first communion.) The trials to which he was subjected were most

humiliating and were apparently sometimes attended with supernatural manifestations.

But Brother John persevered, and in after years often expressed his gratitude

to the relentless instructor who had made it clear to him that self-conquest

was the only sure road to perfection.

In 1420 John was raised to the priesthood. Meanwhile he made extraordinary