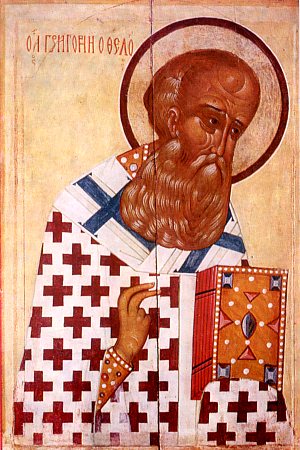

San Gregorio di Nazianzo, Dottore della Chiesa,

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

Patriarche de

Constantinople, docteur de l'Église (+ 390)

Basile

de Césarée et Grégoire de Nazianze sont tous deux nés en Cappadoce.

Basile dans une famille de dix enfants qui deviendront presque tous des saints.

Saint Grégoire est né dans le foyer d'un juif converti qui deviendra évêque.

Ils se rencontrent à Athènes, lors de leurs études, et désormais ils se lient d'une

grande amitié. La même foi et le même désir de perfection animent les deux

étudiants. De retour en Cappadoce, ils font des projets monastiques, mais

l'Eglise a besoin d'évêques dynamiques en cette période troublée par les

hérésies. Basile devient évêque de Césarée.

Grégoire, évêque de Nazianze, le siège épiscopal de son père, puis de

Constantinople. La forte personnalité de Basile en fait un évêque de premier

plan qui défend la foi trinitaire. Il rédige également des règles monastiques,

qui sont encore en vigueur dans les monastères "basiliens". Saint

Grégoire est plus fragile. Chassé de Constantinople, il finira solitaire,

composant d'admirables poèmes que la liturgie utilise encore.

- Saints Basile le Grand et Grégoire Nazianze, évêques et docteurs de l'Eglise (VaticanNews)

Mémoire des saints Basile le Grand et Grégoire de Naziance, évêques et docteurs

de l'Église. Basile, évêque de Césarée en Cappadoce, appelé Grand pour sa

doctrine et sa sagesse, enseigna aux moines la méditation des Écritures, le

labeur de l'obéissance et la charité fraternelle. Il organisa leur vie par des

règles qu'il avait lui-même rédigées. Par ses écrits excellents, il

instruisit les fidèles et se distingua par son souci pastoral des pauvres et

des malades. Il mourut le premier janvier 379. Grégoire, son ami, évêque

successivement de Sasimes, de Constantinople et de Naziance, défendit avec

beaucoup d'ardeur la divinité du Verbe, ce qui lui valut d'être appelé le

Théologien. Il mourut le 25 janvier 390. L'Église se réjouit de célébrer la

mémoire conjointe de si grands docteurs.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saints_356.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI

Mercredi 8 août 2007

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

Chers frères et sœurs!

Mercredi dernier, j'ai

parlé d'un grand maître de la foi, le Père de l'Eglise saint Basile.

Aujourd'hui, je voudrais parler de son ami Grégoire de Nazianze, lui aussi,

comme Basile, originaire de Cappadoce. Illustre théologien, orateur et

défenseur de la foi chrétienne au IV siècle, il fut célèbre pour son éloquence

et avait également, en tant que poète, une âme raffinée et sensible.

Grégoire naquit au sein

d'une noble famille. Sa mère le consacra à Dieu dès sa naissance qui eut lieu

autour de l'an 330. Après une première éducation familiale, il fréquenta les

écoles les plus célèbres de son temps: il fut d'abord à Césarée de Cappadoce,

où il se lia d'amitié avec Basile, futur Evêque de cette ville, puis il

séjourna dans d'autres métropoles du monde antique, comme Alexandrie d'Egypte

et surtout Athènes, où il rencontra de nouveau Basile (cf. Oratio 43, 14-24: SC

384, 146-180). En réévoquant son amitié avec lui, Grégoire écrira plus tard:

"Alors, non seulement je me sentais empli de vénération pour mon grand Basile,

pour ses mœurs sérieuses et la maturité et la sagesse de ses écrits, mais j'en

encourageais également d'autres, qui ne le connaissaient pas encore, à en faire

autant... Nous étions guidés par le même désir de savoir... Telle était notre

compétition: non pas qui était le premier, mais qui permettait à l'autre de

l'être. On aurait dit que nous avions une unique âme et un seul corps"

(Oratio 43, 16.20: SC 384, 154-156.164). Ce sont des paroles qui sont un peu

l'autoportrait de cette noble âme. Mais l'on peut également imaginer que cet

homme, qui était fortement projeté au-delà des valeurs terrestres, a beaucoup

souffert pour les choses de ce monde.

De retour chez lui,

Grégoire reçut le Baptême et s'orienta vers la vie monastique: la solitude, la

méditation philosophique et spirituelle le fascinaient: "Rien ne me semble

plus grand que cela: faire taire ses sens, sortir de la chair du monde, se

recueillir en soi, ne plus s'occuper des choses humaines, sinon celles

strictement nécessaires; parler avec soi-même et avec Dieu, conduire une vie

qui transcende les choses visibles; porter dans l'âme des images divines

toujours pures, sans y mêler les formes terrestres et erronées, être

véritablement le reflet immaculé de Dieu et des choses divines, et le devenir

toujours plus, en puisant la lumière à la lumière...; jouir, dans l'espérance

présente, du bien à venir et converser avec les anges; avoir déjà quitté la

terre, tout en restant sur terre, transporté vers le haut par l'esprit"

(Oratio, 2, 7: SC 247, 96).

Comme il le confie dans

son autobiographie (cf. Carmina [historica] 2, 1, 11 de vita sua 340-349: PG

37, 1053), il reçut l'ordination sacerdotale avec une certaine réticence, car

il savait qu'il aurait dû faire ensuite le Pasteur, s'occuper des autres, de

leurs affaires, et donc ne plus se recueillir ainsi dans la pure méditation:

toutefois, il accepta ensuite cette vocation, et accomplit le ministère

pastoral en pleine obéissance acceptant, comme cela lui arrivait souvent dans

la vie, d'être porté par la Providence là où il ne voulait pas aller. (cf. Jn

21, 18). En 371, son ami Basile, Evêque de Césarée, contre la volonté de

Grégoire lui-même, voulut le consacrer Evêque de Sasimes, une petite ville

ayant une importance stratégique en Cappadoce. Toutefois, en raison de diverses

difficultés, il n'en prit jamais possession et demeura en revanche dans la

ville de Nazianze.

Vers 379, Grégoire fut

appelé à Constantinople, la capitale, pour guider la petite communauté

catholique fidèle au Concile de Nicée et à la foi trinitaire. La majorité

adhérait au contraire à l'arianisme, qui était "politiquement

correct" et considéré comme politiquement utile par les empereurs. Ainsi,

il se trouva dans une situation de minorité, entouré d'hostilité. Dans la petite

église de l'Anastasis, il prononça cinq Discours théologiques (Orationes 27-31:

SC 250, 70-343) précisément pour défendre et rendre également intelligible la

foi trinitaire. Il s'agit de discours demeurés célèbres en raison de la sûreté

de la doctrine, de l'habilité du raisonnement, qui fait réellement comprendre

qu'il s'agit bien de la logique divine. Et la splendeur de la forme également

les rend aujourd'hui fascinants. Grégoire reçut, en raison de ces discours,

l'appellation de "théologien". Ainsi, il fut appelé par l'Eglise

orthodoxe le "théologien". Et cela parce que pour lui, la théologie

n'est pas une réflexion purement humaine, et encore moins le fruit uniquement

de spéculations complexes, mais parce qu'elle découle d'une vie de prière et de

sainteté, d'un dialogue assidu avec Dieu. Et précisément ainsi, elle fait

apparaître à notre raison la réalité de Dieu, le mystère trinitaire. Dans le

silence de la contemplation, mêlé de stupeur face aux merveilles du mystère

révélé, l'âme accueille la beauté et la gloire divine.

Alors qu'il participait

au second Concile œcuménique de 381, Grégoire fut élu Evêque de Constantinople

et assura la présidence du Concile. Mais très vite, une forte opposition se

déchaîna contre lui, jusqu'à devenir insoutenable. Pour une âme aussi sensible,

ces inimitiés étaient insupportables. Il se répétait ce que Grégoire avait déjà

dénoncé auparavant à travers des paroles implorantes: "Nous avons divisé

le Christ, nous qui aimions tant Dieu et le Christ! Nous nous sommes mentis les

uns aux autres à cause de la Vérité, nous avons nourri des sentiments de haine

à cause de l'Amour, nous nous sommes divisés les uns les autres!" (Oratio

6, 3: SC 405, 128). On en arriva ainsi, dans un climat de tension, à sa

démission. Dans la cathédrale bondée, Grégoire prononça un discours d'adieu

d'un grand effet et d'une grande dignité (cf. Oratio 42: SC 384, 48-114). Il

concluait son intervention implorante par ces paroles: "Adieu, grande

ville aimée du Christ... Mes fils, je vous en supplie, conservez le dépôt [de

la foi] qui vous a été confié (cf. 1 Tm 6, 20), souvenez-vous de mes

souffrances (cf. Col 4, 18). Que la grâce de notre Seigneur Jésus Christ soit

avec vous tous" (cf. Oratio 42, 27: SC 384, 112-114).

Il retourna à Nazianze

et, pendant deux ans environ, il se consacra au soin pastoral de cette

communauté chrétienne. Puis, il se retira définitivement dans la solitude, dans

la proche Arianze, sa terre natale, où il consacra à l'étude et à la vie

ascétique. Au cours de cette période, il composa la plus grande partie de son

œuvre poétique, surtout autobiographique: le De vita sua, une relecture en vers

de son chemin humain et spirituel, le chemin exemplaire d'un chrétien qui

souffre, d'un homme d'une grande intériorité dans un monde chargé de conflits.

C'est un homme qui nous fait ressentir le primat de Dieu, et qui nous parle

donc également à nous, à notre monde: sans Dieu, l'homme perd sa grandeur, sans

Dieu, le véritable humanisme n'existe pas. Ecoutons donc cette voix et

cherchons à connaître nous aussi le visage de Dieu. Dans l'une de ses poésies,

il avait écrit, en s'adressant à Dieu: "Sois clément, Toi, l'Au-Delà de

tous" (Carmina [dogmatica] 1, 1, 29: PG 37, 508). Et, en 390, Dieu

accueillait dans ses bras ce fidèle serviteur qui, avec une intelligence aiguë,

l'avait défendu dans ses écrits et qui, avec tant d'amour, l'avait chanté dans

ses poésies.

* * *

J’accueille avec plaisir

les pèlerins francophones, particulièrement les membres du pèlerinage organisé

par les Chanoines réguliers de Saint-Augustin, le groupe de Mende ainsi que les

pèlerins venus d’Égypte. Que le Seigneur vous aide à grandir dans une

connaissance authentique de sa personne pour que vous puissiez en vivre et en

témoigner parmi vos frères! Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique.

© Copyright 2007 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Gregory the Theologian (= Gregory of Nazianzus): fresco from Kariye Camii, Istanbul.

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI

Mercredi 22 août 2007

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

Chers frères et sœurs,

Dans le cadre des

portraits des grands Pères et Docteurs de l'Eglise que je cherche à offrir dans

ces catéchèses, j'ai parlé la dernière fois de saint Grégoire de Nazianze,

Evêque du IV siècle, et je voudrais aujourd'hui encore compléter ce portrait

d'un grand maître. Nous chercherons aujourd'hui à recueillir certains de ses

enseignements. En réfléchissant sur la mission que Dieu lui avait confiée,

saint Grégoire de Nazianze concluait: "J'ai été créé pour m'élever jusqu'à

Dieu à travers mes actions" (Oratio 14, 6 de pauperum amore: PG 35, 865).

De fait, il plaça son talent d'écrivain et d'orateur au service de Dieu et de

l'Eglise. Il rédigea de multiples discours, diverses homélies et panégyriques,

de nombreuses lettres et œuvres poétiques (près de 18.000 vers!): une activité

vraiment prodigieuse. Il avait compris que telle était la mission que Dieu lui

avait confiée: "Serviteur de la Parole, j'adhère au ministère de la

Parole; que jamais je ne néglige ce bien. Cette vocation je l'apprécie et je la

considère, j'en tire plus de joie que de toutes les autres choses mises

ensemble" (Oratio 6, 5: SC 405, 134; cf. également Oratio 4, 10).

Grégoire de Nazianze

était un homme doux, et au cours de sa vie il chercha toujours à accomplir une

oeuvre de paix dans l'Eglise de son temps, lacérée par les discordes et les

hérésies. Avec audace évangélique, il s'efforça de surmonter sa timidité pour

proclamer la vérité de la foi. Il ressentait profondément le désir de

s'approcher de Dieu, de s'unir à Lui. C'est ce qu'il exprime lui-même dans

l'une de ses poésies, où il écrit: parmi les "grands flots de la mer de la

vie, / agitée ici et là par des vents impétueux, / ... / une seule chose

m'était chère, constituait ma richesse, / mon réconfort et l'oubli des peines,

/ la lumière de la Sainte Trinité" (Carmina [historica] 2, 1, 15: PG 37,

1250sq.).

Grégoire fit resplendir

la lumière de la Trinité, en défendant la foi proclamée par le Concile de

Nicée: un seul Dieu en trois personnes égales et distinctes - le Père, le Fils

et l'Esprit Saint -, "triple lumière qui en une unique / splendeur se

rassemble" (Hymne vespéral: Carmina [historica] 2, 1, 32: PG 37, 512).

Dans le sillage de saint Paul (1 Co 8, 6), Grégoire affirme ensuite, "pour

nous il y a un Dieu, le Père, dont tout procède; un Seigneur, Jésus Christ, à

travers qui tout est; et un Esprit Saint en qui tout est" (Oratio 39, 12:

SC 358, 172).

Grégoire a profondément

souligné la pleine humanité du Christ: pour racheter l'homme dans sa totalité,

corps, âme et esprit, le Christ assuma toutes les composantes de la nature

humaine, autrement l'homme n'aurait pas été sauvé. Contre l'hérésie d'Apollinaire,

qui soutenait que Jésus Christ n'avait pas assumé une âme rationnelle, Grégoire

affronte le problème à la lumière du mystère du salut: "Ce qui n'a pas été

assumé, n'a pas été guéri" (Ep 101, 32: SC 208, 50), et si le Christ

n'avait pas été "doté d'une intelligence rationnelle, comment aurait-il pu

être homme?" (Ep 101, 34: SC 208, 50). C'était précisément notre

intelligence, notre raison qui avait et qui a besoin de la relation, de la

rencontre avec Dieu dans le Christ. En devenant homme, le Christ nous a donné

la possibilité de devenir, à notre tour, comme Lui. Grégoire de Nazianze

exhorte: "Cherchons à être comme le Christ, car le Christ est lui aussi

devenu comme nous: cherchons à devenir des dieux grâce à Lui, du moment que

Lui-même, par notre intermédiaire, est devenu homme. Il assuma le pire, pour

nous faire don du meilleur" (Oratio 1, 5: SC 247, 78).

Marie, qui a donné la

nature humaine au Christ, est la véritable Mère de Dieu (Theotókos: cf Ep. 101,

16: SC 208, 42, et en vue de sa très haute mission elle a été

"pré-purifiée" (Oratio 38, 13: SC 358, 132, comme une sorte de

lointain prélude du dogme de l'Immaculée Conception). Marie est proposée comme

modèle aux chrétiens, en particulier aux vierges, et comme secours à invoquer

dans les nécessités (cf. Oratio 24, 11: SC 282, 60-64).

Grégoire nous rappelle

que, comme personnes humaines, nous devons être solidaires les uns des autres.

Il écrit: ""Nous sommes tous un dans le Seigneur" (cf. Rm 12,

5), riches et pauvres, esclaves et personnes libres, personnes saines et

malades; et la tête dont tout dérive est unique: Jésus Christ. Et, comme le

font les membres d'un seul corps, que chacun s'occupe de chacun, et tous de

tous". Ensuite, en faisant référence aux malades et aux personnes en

difficulté, il conclut: "C'est notre unique salut pour notre chair et

notre âme: la charité envers eux" (Oratio 14, 8 de pauperum amore: PG 35,

868ab). Grégoire souligne que l'homme doit imiter la bonté et l'amour de Dieu,

et il recommande donc: "Si tu es sain et riche, soulage les besoins de

celui qui est malade et pauvre; si tu n'es pas tombé, secours celui qui a chuté

et qui vit dans la souffrance; si tu es heureux, console celui qui est triste;

si tu as de la chance, aide celui qui est poursuivi par le mauvais sort. Donne

à Dieu une preuve de reconnaissance, car tu es l'un de ceux qui peuvent faire

du bien, et non de ceux qui ont besoin d'en recevoir... Sois riche non

seulement de biens, mais également de piété; pas seulement d'or, mais de

vertus, ou mieux, uniquement de celle-ci. Dépasse la réputation de ton prochain

en te montrant meilleur que tous; fais toi Dieu pour le malheureux, en imitant

la miséricorde de Dieu" (Oratio 14, 26 de pauperum amore: PG 35, 892bc).

Grégoire nous enseigne

tout d'abord l'importance et la nécessité de la prière. Il affirme qu'il

"est nécessaire de se rappeler de Dieu plus souvent que l'on respire"

(Oratio 27, 4: PG 250, 78), car la prière est la rencontre de la soif de Dieu

avec notre soif. Dieu a soif que nous ayons soif de Lui (cf. Oratio 40, 27: SC

358, 260). Dans la prière nous devons tourner notre coeur vers Dieu, pour nous

remettre à Lui comme offrande à purifier et à transformer. Dans la prière nous

voyons tout à la lumière du Christ, nous ôtons nos masques et nous nous

plongeons dans la vérité et dans l'écoute de Dieu, en nourrissant le feu de

l'amour.

Dans une poésie, qui est

en même temps une méditation sur le but de la vie et une invocation implicite à

Dieu, Grégoire écrit: "Tu as une tâche, mon âme, / une grande tâche si tu le

veux. / Scrute-toi sérieusement, / ton être, ton destin; / d'où tu viens et où

tu devras aller; / cherche à savoir si la vie que tu vis est vie / ou s'il y a

quelque chose de plus. / Tu as une tâche, mon âme, / purifie donc ta vie: /

considère, je te prie, Dieu et ses mystères, / recherche ce qu'il y avait avant

cet univers / et ce qu'il est pour toi, / d'où il vient, et quel sera son

destin. / Voilà ta tâche, /mon âme, / purifie donc ta vie" (Carmina

[historica] 2, 1, 78: PG 37, 1425-1426). Le saint Evêque demande sans cesse de

l'aide au Christ, pour être relevé et reprendre le chemin: "J'ai été déçu,

ô mon Christ, / en raison de ma trop grande présomption: / des hauteurs je suis

tombé profondément bas. / Mais relève-moi à nouveau à présent, car je vois /

que j'ai été trompé par ma propre personne; / si je crois à nouveau trop en

moi, / je tomberai immédiatement, et la chute sera fatale" (Carmina

[historica] 2, 1, 67: PG 37, 1408).

Grégoire a donc ressenti

le besoin de s'approcher de Dieu pour surmonter la lassitude de son propre moi.

Il a fait l'expérience de l'élan de l'âme, de la vivacité d'un esprit sensible

et de l'instabilité du bonheur éphémère. Pour lui, dans le drame d'une vie sur

laquelle pesait la conscience de sa propre faiblesse et de sa propre misère,

l'expérience de l'amour de Dieu l'a toujours emporté. Ame, tu as une tâche -

nous dit saint Grégoire à nous aussi - , la tâche de trouver la véritable

lumière, de trouver la véritable élévation de ta vie. Et ta vie est de

rencontrer Dieu, qui a soif de notre soif.

***

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins francophones présents ce matin, en particulier les pèlerins du diocèse

d’Obala, au Cameroun, les appelant, à l’exemple de saint Grégoire de Nazianze,

à trouver dans l’écoute de la Parole de Dieu et dans la charité envers les

pauvres la volonté de servir toujours davantage le Christ et l’Église.

© Copyright 2007 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Gregory of Nazianzus in Constantinople. Григорий Богослов приезжает в Константинополь. http://www.pravoslavieto.com/life/01.25_sv_Grigorij_Bogoslov.htm

Saints Basile et saint

Grégoire

Évêques et docteurs de

l'Eglise

Depuis la réforme du

calendrier par Paul VI, en célébrant ensemble saint Basile le Grand, évêque de

Césarée et saint Grégoire de Nazianze, évêque de Sazimes puis patriarche de

Constantinople, l’Eglise veut souligner la vertu de leur amitié exemplaire.

Saint Basile de Césarée

et saint Grégoire de Nazianze naquirent en Cappadoce, vers 330, l’un à Césarée

de Cappadoce et l’autre à Arianze ; tous les deux appartenaient à des familles

éminemment chrétiennes puisque le premier, fils et petit-fils de saintes, était

le frère de saint Grégoire de Nysse, de saint Pierre de Sébaste et de sainte Macrine

la Jeune, tandis que le second était le fils de Grégoire l’Ancien, évêque de

Nazianze. Les deux amis qui avaient reçu une solide éducation, se rencontrèrent

à l’école de Césarée mais ne lièrent indéfectiblement qu’à l’école d’Athènes

quand Basile revint de l’école de Constantinople et Grégoire de celle

d’Alexandrie. Ensemble, ils furent moines, près de Néo-Césarée, dans le Pont,

où ils composèrent ensemble la Philocalie et écrivirent deux règles

monastiques.

Basile fut élu évêque de

Césarée (370), en même temps qu’il était fait métropolite de Cappadoce et

exarque du Pont ; quand il créa de nouveaux sièges épiscopaux, il fit confier à

Grégoire qu’il consacra, celui de Sazimes (371). En 379, Grégoire fut désigné

pour réorganiser l’Eglise de Constantinople dont il fut nommé patriarche par

l’empereur Théodose I° et confirmé par le concile de 381 ; la légitimité de sa

nomination étant contestée, il démissionna et, après avoir un temps administré

le diocèse de Nazianze, il se retira dans sa propriété d’Arianze où il mourut

en 390.

Quant à saint Basile, son

activité comme prêtre, apôtre de la charité et prince de l’Eglise, lui a

procuré de son vivant le surnom de Grand. Une importance particulière s’attache

à sa lutte victorieuse contre l’arianisme si puissant sous le règne de

l’empereur Valens. l’Empereur ne put porter atteinte qu’à la position

extérieure de saint Basile en partageant la Cappadoce en deux provinces (371),

ce qui amenait aussi le partage de la province métropolitaine (une cinquantaine

d’évêchés suffragants). Pour assurer de façon durable l’orthodoxie mise en

péril en Orient, saint Basile chercha, par l’entremise de saint Athanase et par

une prise directe de contact avec le pape Damase, à nouer de meilleures

relations et à obtenir une politique unanime des évêques d’Orient et

d’Occident. L’obstacle principal à l’union souhaité entre les épiscopats

d’Orient et d’Occident était le schisme mélécien d’Antioche ; les tentatives de

saint Basile pour obtenir la reconnaissance de Mélèce en Occident demeurèrent

sans résultat puisque le Pape ne voulait pas abandonner Paulin. Basile fut

moins comme un spéculatif qu’un évêque d’abord attaché à l’exploitation

pratique et pastorale des vérités de la foi.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/01/02.php

SAINT GRÉGOIRE de

NAZIANZE

Évêque, Docteur de l'Église

(312-389)

La mère de saint Grégoire

dut la naissance de ce fils à ses prières et à ses larmes. Elle se chargea

elle-même de sa première éducation et lui apprit à lire, à comprendre et à

aimer les Saintes Écritures. L'enfant devint digne de sa sainte mère, et

demeura pur au milieu des séductions.

"Un jour, raconte-t-il

lui-même, j'aperçus près de moi deux vierges d'une majesté surhumaine. On

aurait dit deux soeurs. La simplicité et la modestie de leurs vêtements, plus

blancs que la neige, faisaient toute leur parure. A leur vue, je tressaillis

d'un transport céleste. "Nous sommes la Tempérance et la Chasteté, me

dirent-elles; nous siégeons auprès du Christ-Roi. Donne-toi tout à nous, cher

fils, accepte notre joug, nous t'introduirons un jour dans les splendeurs de

l'immortelle Trinité." La voie de Grégoire était tracée: il la suivit sans

faiblir toute sa vie.

Il s'embarqua pour

Athènes, afin de compléter ses études. Dieu mit sur le chemin de Grégoire, dans

la ville des arts antiques, une âme grande comme la sienne, saint Basile. Qui

dira la beauté et la force de cette amitié, dont le but unique était la vertu!

"Nous ne connaissions que deux chemins, raconte Grégoire, celui de

l'église et celui des écoles." La vertu s'accorde bien avec la science;

partout où l'on voulait parler de deux jeunes gens accomplis, on nommait Basile

et Grégoire.

Revenus dans leur patrie,

ils se conservèrent toujours cette affection pure et dévouée qui avait

sauvegardé leur jeunesse, et qui désormais fortifiera leur âge mûr et consolera

leur vieillesse. Rien de plus suave, de plus édifiant que la correspondance de

ces deux grands hommes, frères d'abord dans l'étude, puis dans la solitude de

la vie monastique et enfin dans les luttes de l'épiscopat.

A la mort de son père,

qui était devenu évêque de Nazianze, Grégoire lui succède; mais, au bout de

deux ans, son amour de la solitude l'emporte, et il va se réfugier dans un

monastère. Bientôt on le réclame pour le siège patriarcal de Constantinople. Il

résiste: "Jusqu'à quand, lui dit-on, préférerez-vous votre repos au bien

de l'Église?" Grégoire est ému; il craint de résister à la Volonté divine

et se dirige vers la capitale de l'empire, dont il devient le patriarche

légitime. Là, sa mansuétude triomphe des plus endurcis, il fait l'admiration de

ses ennemis, et il mérite, avec le nom de Père de son peuple, le nom glorieux

de Théologien, que l'Église a consacré. Avant de mourir, Grégoire se retira à

Nazianze, où sa vie s'acheva dans la pratique de l'oraison, du jeûne et du

travail.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_gregoire_de_nazianze.html

Gregory of Nazianzus (russian icon), 16th century, http://days.pravoslavie.ru/Images/ii535&37.htm

Heureux prélude

Bien peu de gens honorent

les Maccabées, sous prétexte que leur lutte n’a pas eu lieu après le Christ,

eux qui sont pourtant dignes d’être honorés de tous parce que leur endurance

s’est exercée pour la défense des institutions de leurs pères ! Et que

n’auraient fait les hommes qui ont subi le martyre avant la passion du Christ,

s’ils avaient été persécutés après le Christ et l’avaient imité dans sa mort

pour nous ? Car ceux qui, sans l’aide d’un pareil exemple, ont fait preuve

d’une si grande vertu, comment ne se seraient-ils pas montrés plus nobles encore

dans des dangers affrontés après cet exemple ?

Voici Éléazar, prémices

de ceux qui sont morts avant le Christ, comme Étienne l’a été de ceux qui sont

morts après le Christ. C’est un saint homme et un vieillard, aux cheveux

blanchis et par la vieillesse et par la prudence. Auparavant il sacrifiait pour

le peuple et priait, mais maintenant c’est lui-même qu’il offre à Dieu en

sacrifice très parfait, victime expiatoire de tout le peuple, heureux prélude

de la lutte, exhortation parlante et silencieuse. Il offre aussi les sept

enfants, l’accomplissement de son éducation, en sacrifice vivant,

saint, capable de plaire à Dieu (Rm 12, 1), plus splendide et plus pur que

tout sacrifice conforme à la Loi. Car il est parfaitement juste et légitime de

porter au compte du père les actions des enfants. Imitons Éléazar, qui a montré

le meilleur exemple en parole et en acte.

St Grégoire de Nazianze

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze († v. 390), docteur de l’Église, est le premier après saint Jean à

avoir été surnommé le « Théologien » pour la profondeur de ses

discours sur Dieu. / Discours 15,1.3.12, trad. R. Ziadé, Les

martyrs Maccabées : de l’histoire juive au culte chrétien, Leyde, Brill, 2007,

p. 301-302, 311.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/mardi-16-novembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Heureux, par diverses

voies

Heureux celui qui mène

une vie tranquille, sans se mêler à ceux dont les voies sont terrestres, et qui

a élevé son esprit vers Dieu.

Heureux celui qui, mêlé à

la multitude, ne se tourne pas vers une multitude de choses, mais a adressé à

Dieu tout son cœur.

Heureux celui qui, au

prix de tout ce qu’il possédait, a acheté le Christ, a la croix pour seule

possession et la porte bien haut.

Heureux celui qui, maître

de ses légitimes possessions, tend la main de Dieu à ceux qui en ont besoin.

Heureux celui qui,

exerçant le pouvoir sur le peuple, avec de purs et grands sacrifices conduit le

Christ aux terriens.

Toutes ces vies

remplissent les pressoirs célestes, qui sont là pour accueillir le fruit de nos

âmes.

St Grégoire de Nazianze

Saint Grégoire de Nazianze

(† v. 390), docteur de l’Église, est le premier après saint Jean à avoir été

surnommé le « Théologien » pour la profondeur de ses discours sur

Dieu. / Les Béatitudes des divers modes de vie, trad. G. Bady, in

Dominicat, Paris, Cerf/Magnificat, 2020, p. 420-421.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/mardi-1-novembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Digne de le

recevoir ?

Se lancer dans la

théologie, je sais que c’est téméraire. Nul n’est digne du Dieu suprême, à la

fois victime et grand prêtre, s’il n’a pas commencé par s’offrir lui-même à

Dieu en offrande vivante, bien plus, s’il ne s’est pas fait le temple saint et

vivant du Dieu vivant. Sachant cela, comment pourrais-je me charger

témérairement de m’occuper de la parole de Dieu ou approuver celui qui s’en

charge sans réfléchir ? Le désirer n’est pas louable ; s’en charger

est redoutable.

Il faut donc commencer

par se purifier soi-même, ensuite s’entretenir avec l’Être pur. Sinon nous en

viendrions à subir le sort de Manoué et à dire, en imaginant que nous sommes en

présence de Dieu : « Femme, c’en est fait de nous, nous avons vu

Dieu » (Jg 13, 22) ; ou, comme le célèbre centurion, nous

implorerions la guérison en refusant de recevoir chez nous le guérisseur. Aussi

longtemps qu’on est le centurion qui commande une centurie de malices et

davantage, et qu’on reste au service d’un César qui gouverne l’univers des

réalités terre à terre, que chacun de nous dise à son

tour : « Je ne suis pas digne que tu entres sous mon

toit. » Mais, lorsque je verrai Jésus, bien que je sois petit comme

le célèbre Zachée par la stature spirituelle, et que je grimperai moi aussi

dans le sycomore en mortifiant mes membres terrestres et en réduisant à rien le

corps de ma bassesse, alors aussi je recevrai Jésus chez moi, je l’entendrai

dire : « Aujourd’hui le salut est arrivé pour cette

maison » (Lc 19, 9).

St Grégoire de Nazianze

Cappadocien, saint

Grégoire de Nazianze († 390) a été surnommé « le Théologien » pour la

profondeur de ses discours sur Dieu. / Discours 20, 1.4, trad. J. Mossay et G.

Lafontaine, Paris, Cerf, 1980, Sources Chrétiennes 270, p. 59.63-65.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/lundi-18-septembre-2/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Icône

russe du xviiie siècle, représentant Jean

Chrysostome et Grégoire de Nazianze.

Святители

Иоанн Златоуст и Григорий Богослов. Икона XVIII в. Россия

John

Chrysostom and Gregory Nazianzus.

Icon

02036 Svyatiteli Ioann Zlatoust i Grigorij Bogoslov. Ikona XVIII v. Rossiya

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

Naissance:

Deux hypothèses ont été proposées au sujet de la chronologie de sa carrière.

L'historiographie ancienne et la tradition byzantine rapportée par la Souda

(Suidae Lexicon, éd. A. ADLER, Leipzig, 1928, p. 541-543), font état de son

grand âge; il serait mort nonagénaire en 390. Les historiens modernes et

l'hagiographie récente adoptent une chronologie plus brève et placent sa

naissance vers 325/329. Cette chronologie courte s'appuie sur le postulat selon

lequel Grégoire aurait eu approximativement le même âge que S. Basile et sur

l'interprétation de plusieurs textes poétiques et ambigus. Cette hypothèse

explique mal les nombreuses allusions que Grégoire fait à son grand âge, dès

l'époque de son ordination sacerdotale (Or. 2, 12). D'autre part, il dit

formellement que sa mère, Nonna, était quinquagénaire en 325. La biographie

longue est notamment défendue par le bollandiste Daniel Papebroch (Acta

Sanctorum, Maii t. 2, p. 370D - 371F).

Études:

Grégoire est intentionnellement discret sur la période de ses études (De vita

sua, v. 108 et 211-212), et l'on ignore combien d'années il y a consacrées. Il

étudia à Césarée de Cappadoce, à Césarée de Palestine et à Alexandrie. En

Palestine, il fut, selon Saint Jérôme (De viris illustribus, 113), élève de

Thespesius et condisciple d'Euzoius, futur évêque arien de Césarée. A-t-il été

l'auditeur de S. Cyrille de Jérusalem, dans cette dernière ville, en 348 ou

349? Cela expliquerait l'importance des réminiscences de la VIe et de la IXe

Catéchèses de Cyrille dans l'Or. 28 (BERNARDI, Prédication, p. 185; SINKO, De

traditione, I, 12-18). Fut-il élève de Libanius à Antioche, comme l'affirme

Socrate (Hist. eccl., IV, 26)? C'est possible. D'Alexandrie, il gagna Athènes

avec une hâte qu'il fait remarquer sans l'expliquer en racontant les détails de

cette traversée mouvementée. Il ne fut pas étudiant pendant toute la durée de

son séjour dans les écoles d'Athènes. Il y enseigna. Lorsque Basile de Césarée

vint à Athènes comme étudiant, Grégoire l'accueillit et l'introduisit dans les

milieux athéniens. Il partageait les goûts de Basile pour la vie religieuse et

il décida de suivre lui aussi une vocation de type monastique mal précisé; on

ignore à quel moment, entre 354/355 et 363, il renonça à la carrière profane et

rentra au pays.

Carrière religieuse en Cappadoce:

Les Invectives contre Julien (Or. 4 et 5), composées sans doute vers 364, selon

M. Regali, sont des polémiques contre l'hellénisme à l'antique, que des lettrés

païens encouragés par l'empereur Julien (361-363) remettaient à la mode.

Ordonné prêtre sous le règne de Julien ou de Valens (365-378), il composa à

cette occasion un traité sur le sacerdoce (Or. 2). Sa carrière sacerdotale puis

épiscopale en Cappadoce jusqu'en 374 est celle d'un ecclésiastique jouant le

rôle de notable en même temps qu'il partage les charges pastorales de son vieux

père, dans la bourgade montagnarde de Nazianze à l'écart des grands centres. Il

évoque dans ses écrits des réactions monastiques défavorables aux positions

doctrinales de son père, des divergences théologiques sollicitant le clergé

divisé entre nicéens et neo-nicéens d'une part, et entre diverses tendances

dérivées de l'arianisme d'autre part; il intervient avec son père dans

l'élection de S. Basile comme évêque de Césarée, mais quand Basile l'a fait

sacrer évêque de Sasimes, il lui reproche d'avoir abusé de lui et de manquer

d'égards à son âge. En effet, il néglige obstinément de s'installer à Sasimes,

bourg qu'il dit peu plaisant. Les raisons administratives et ecclésiastiques

qui l'avaient amené là ne dissimulent guère des questions doctrinales et

personnelles sous-jacentes. Grégoire resta à Nazianze comme auxiliaire de son

père jusqu'à la mort de ce dernier, survenue en 374; comme on tardait à donner

un successeur à son père, Grégoire, faisant valoir son âge, se retira à

Séleucie de Pisidie.

Séjour à Constantinople:

En 379, la communauté nicéenne de Constantinople fit appel à lui; les ariens de

tendances diverses étaient majoritaires dans la capitale. Il organisa les

services religieux dans une maison particulière, l'Anastasia, qui devint plus

tard l'église Ste-Anastasie. Lorsque Théodose Ier, favorable aux nicéens

orthodoxes, insalla ceux-ci dans les églises officielles, Grégoire hésita à se

laisser introniser à la Grande Église par le pouvoir civil, mais il fut comme

plébiscité par le peuple et le clergé quelques jours après le 24 nov. 380. En

381, le 1er concile de Constantinople valida les fonctions d'évêque de

Constantinople qu'il exerçait. Mais des dissensions éclatèrent entre les

évêques d'Orient et d'Occident, on remit en question la légitimité des

fonctions de Grégoire. En fait la question du rôle ecclésiastique du siège de

la Nouvelle Rome dans la chrétienté et celle de la légitimité politique de

l'orthodoxie étaient posées; Grégoire renonça à la présidence du concile en

même temps qu'au trône épiscopal et regagna Nazianze.

Les dernières années en Cappadoce:

De retour à Nazianze, il y administra l'église locale en attendant qu'on lui

donne un titulaire dans la personne d'un de ses parents, Eulalios. Retiré dans

son domaine d'Arianze, avec l'intention de limiter son ministère aux activités

littéraires, Grégoire y mourut et y fut inhumé, en 390.

SOURCE : http://nazianzos.fltr.ucl.ac.be/002BiosEF.htm

Basil

of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, John Chrysostom. Orthodoxy icon.

Три

святителя: Василий Великий, Григорий Богослов, Иоанн Златоуст. Русская

православная икона.

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

Fête saint : 09 Mai

Présentation

Titre : Surnommé le

Théologien

Date : 312-389

Pape : Saint Melchiade ;

Saint Sirice

Empereur : Constantin ;

Théodose

La Vie des Saints : Saint

Grégoire de Nazianze

Auteur

Mgr Paul Guérin

Les Petits Bollandistes

- Vies des Saints - Septième édition - Bloud et Barral - 1876 -

Saint Grégoire de

Nazianze

À Nazianze, le

bienheureux décès de saint Grégoire, évêque, surnommé le Théologien ; à cause

de la grande science qu'il avait des choses divines. Il releva à Constantinople

la foi catholique qui y était fort déchue, et réprima les hérésies qui

s'élevèrent de son temps. + 389.

Hagiographie

Près de la petite ville

de Nazianze, en Cappadoce, dans un bourg nommé Arianze, vivait, au commencement

du IVe siècle, une sainte femme qui s’appelait Nonna. Elle était fervente

chrétienne ; son mari, Grégoire, avait une âme droite ; mais il était païen, —

d’une secte monothéiste, il est vrai : les hypsistaires, c’est-à-dire les

adorateurs du Très-Haut. Tous deux appartenaient à une noble race et

possédaient une belle fortune ; Grégoire avait même occupé les premières charges

de Nazianze. Nonna était heureuse selon le monde ; mais elle avait deux

chagrins cuisants : son mari n’avait pas sa foi ; Dieu ne lui avait donné

qu’une fille, et déjà Grégoire et elles avaient passé cinquante ans. Enfin le

Seigneur écouta son ardente prière : il lui accorda deux fils, Grégoire et

Césaire ; et leur père, touché de la grâce, se convertit en 325, Du premier

pas, s’élevant aux cimes, il se montra si fervent, que le clergé et le peuple

le choisirent pour évêque ; il gouverna l’église de Nazianze

pendant quarante-cinq ans et mourut presque centenaire. Bien plus : la

famille entière, Grégoire l’Ancien, Nonna, leurs enfants Gorgonie, Grégoire,

Césaire, ont obtenu les honneurs des Saints.

Grégoire, l’aîné des

fils, de bien bonne heure, avait été prévenu de la grâce. Il a raconté comment,

dans sa prime jeunesse, il eut une vision, un songe « qui lui inspira sans

peine l’amour de la virginité ». Deux vierges lui apparurent, d’une beauté

céleste et d’une ravissante modestie. « Elles n’avaient d’autre parure que de

n’en avoir pas… Leurs têtes et leurs visages étaient voilés, leurs yeux

baissés, leurs lèvres closes. » À la demande de l’enfant : « Nous sommes,

dirent-elles, la Chasteté et la Tempérance. Près du Christ-Roi, nous nous

plaisons à la vue des vierges qui habitent le Paradis. Courage, enfant ! Unis

ton cœur à nos cœurs, afin que nous puissions te mettre en présence de

splendeurs de l’éternelle Trinité. » Elles l’embrassèrent et disparurent,

laissant « son cœur ravi de cette radieuse image de la chasteté ».

Grégoire fut fidèle à

cette très sainte invitation ; dès lors, son âme fut acquise à la vertu. Mais

en même temps l’étude le passionnait et il y montrait autant de talent que

d’ardeur. Il était d’usage alors d’aller, dans les villes étrangères, écouter les

professeurs célèbres. Grégoire n’en eut que de tels ; mais en même temps, bien

gouverné par son père, il ne s’attacha qu’à des maîtres chrétiens.

Césarée, Constantinople, Alexandrie, Athènes le virent successivement. Il

n’était pas baptisé encore, malgré la piété de ses parents, qui suivaient sur

ce point la fâcheuse habitude de leur temps. Dieu le rappela au devoir de cette

initiation, en le laissant exposé à une terrible tempête d’abord, entre

Alexandrie et Rhodes, puis à un tremblement de terre épouvantable à Athènes. Le

jeune homme promit à Dieu de recevoir le baptême le plus tôt possible. Il tint

parole ; mais on ne sait si ce fut dans cette dernière ville ou à Nazianze.

À Athènes, il se lia

d’une étroite amitié avec Basile, jeune Cappadocien du Pont ; arrivé quelque

temps avant lui, Grégoire put, grâce à cette circonstance, rendre à Basile des

services qui contribuèrent à les unir. Dès lors cette affection mutuelle devint

célèbre ; on la compara à celle d’Oreste et de Pylade, de David et de Jonathas ;

elle, est restée le modèle des amitiés juvéniles. C’est justice, car elle

ne servit qu’à enflammer mutuellement leur zèle pour la science et pour la

vertu.

« Nous ne connaissions, a

écrit Grégoire, que deux routes : celle de l’église et celle de l’école. »

Bien différents d’un

condisciple, appelé à une tout autre notoriété, Julien, celui qui serait

l’Apostat, et pour lequel dès lors les deux amis conçurent une aversion

trop justifiée.

Quand Basile, rappelé

dans le Pont, partit d’Athènes, Grégoire voulut le suivre. Mais il fut arrêté,

déjà presque sur le navire, par la foule des étudiants, qui, quasi de force, le

ramelièrent et l’assirent dans une chaire de professeur. Cette violence

honorable ne le retint guère ; peu après il s’échappa et vint rejoindre son ami

dans la solitude où il s’était enfermé et avait fondé une petite société de

cénobites. Tous deux s’y livrèrent à une étude profonde des saintes Lettres,

éclairée par celle de la Tradition et des premiers écrivains ecclésiastiques.

Là furent jetés les fondements de cette science éminente de la foi qui leur ont

valu à tous deux le titre de docteur de l’Église et à Grégoire le surnom de

Théologien.

La pieuse union ne dura

que trop peu d’années. Le vieil évêque de Nazianze ne pouvait plus se passer

d’une aide ; il réclama celle de son fils, et celui-ci répondit à son devoir

filial. Malgré la résistance de son humilité, il fut alors élevé à l’honneur du

sacerdoce ; prêtre, il commença cette merveilleuse carrière d’orateur où il

s’est égalé aux plus éloquents maîtres de la parole, s’il ne les a pas

surpassés.

Il était à Nazianze

lorsque Julien, monté sur le trône, exerça contre les chrétiens son hypocrite

persécution. L’Apostat avait interdit aux fidèles du Christ les écoles et

l’enseignement des auteurs de l’antiquité. L’indignation de Grégoire fut

grande.

« Qu’avec moi,

s’écria-t-il, se courrouce quiconque aime l’éloquence et appartient comme moi

au monde de ceux qui la cultivent… Car je l’aime plus que toute autre chose,

seules exceptées les choses divines et les invisibles espérances ! »

Peut-être même prit-il

part à la tentative des deux Apollinaires, rhéteurs de Laodicée, qui essayèrent

de remplacer par des compositions chrétiennes les chefs-d’œuvre antiques qu’ils

ne pouvaient plus commenter. Car Grégoire était poète autant qu’orateur ; il a

laissé plus de vingt mille vers, et Villemain a pu en dire qu’ils révèlent «

deux dons précieux, la grâce naturelle et la mélancolie vraie ». Et il ajoute :

« On l’a appelé le

Théologien de l’Orient ; il faudrait surtout l’appeler le Poète du

christianisme oriental. »

L‘âge de la paix

studieuse était passé pour Grégoire. Sa vie active lui réservait des déboires

cruels et des combats, toujours vaillants, mais douloureux. Sa santé, dès lors

atteinte, peut-être, par les froids humides de sa retraite du Pont, ne devait

plus se remettre ; du reste à elles seules ses austérités l’eussent

compromises, et les épreuves dont il fut assailli la ruinèrent. D’ailleurs son

humilité, son goût pour la vie contemplative et l’étude, luttant contre les

honneurs et les charges dont on prétendait les accabler, lui causaient des

angoisses et des répugnances qui parfois peut-être le rendirent moins apte aux

résultats heureux attendus de son génie et de sa vertu. Son ami Basile le fit

sacrer évêque de Sasime : c’était bien malgré lui, de force même ; aussi dès la

première occasion renonça-t-il à ce siège ; et, revenu à Nazianze, ce ne fut

pas sans une nouvelle et longue résistance qu’il consentit à devenir le

coadjuteur de son père.

Il ne le resta pas

longtemps. Le vénérable évêque mourut en 374. Grégoire essaya, mais en vain, de

lui faire donner un successeur ; il dut conserver, à titre provisoire, le

gouvernement de son église. Mais en 378, il fut fortement sollicité de

venir porter secours à celle de Constantinople, ravagée par les hérésies d’Anus

et de Macédonius. Son zèle ne put s’y refuser ; bientôt il eut reconstitué,

raffermi, multiplié le petit troupeau orthodoxe. C’est alors qu’il écrivit

les Cinq Discours théologiques, qui font les cinq parties d’un traité

complet sur la Trinité, œuvre magistrale, point culminant de son génie et de

son éloquence. Aussi le concile de Constantinople, en 381, voulut qu’il

acceptât le siège épiscopal de cette ville, où l’appelait le vœu unanime des

fidèles. Mais il ne l’occupa que peu de mois. Bientôt il se trouva en

opposition avec les Pères du concile au sujet de la succession à l’église

d’Antioche et crut comprendre qu’il n’avait plus leur confiance. Il offrit donc

sa démission, et elle fut acceptée avec un étrange empressement. Le peuple,

rempli de douleur, voulut s’opposer à son départ ; tout fut inutile. Grégoire,

libéré avec le consentement de l’empereur Théodose, reprit le gouvernement de

l’église de Nazianze. Il s’y occupa surtout de faire enfin nommer un successeur

à son père.

Désormais, — on était à

la fin de 383, — il vécut retiré dans sa petite propriété d’Arianze, où il

était né. On peut dire que les six ans qui lui restaient à vivre furent une

longue mort. Les souffrances de son pauvre corps se doublaient des souffrances,

plus cruelles, de son âme : tentations pénibles, scrupules achevaient, au

milieu des austérités qu’il ajoutait à ses douleurs, de purifier sa sainte âme.

Il ne cessait pourtant d’écrire. En prose, en vers, il continuait le bon combat

de la foi. Non pas certes qu’il n’aimât point la paix ; rien ne lui était plus

cher. Mais il se croyait tenu de faire, jusqu’à la fin, valoir le talent remis

par Dieu entre ses mains. Et c’est ainsi que, peu avant de mourir, il écrivait

encore au patriarche Nectaire de Constantinople, pour lui dénoncer l’hérésie et

les excès des apollinaristes.

Enfin, « l’incomparable

orateur de Nazianze, le champion intrépide de la Trinité, le doux et triste

archevêque de Constantinople », — ainsi le nomme de Broglie, — alla prendre

au sein de Dieu son éternel repos le 9 mai 389, à l’âge d’environ 64 ans.

Écrits de saint Grégoire

La seule édition

grecque-latine complète des œuvres de saint Grégoire de Nazianze, est celle de

M. l’abbé Migne, tomes XXXV à XXXVIII de la Patrologie. Ces œuvres sont :

1°)

Des Discours au nombre de quarante-cinq. Les plus fameux sont les

cinq discours dits Théologiques contre les Eunomiens et les

Macédoniens ; en faveur de la divinité du Fils de Dieu et l’Esprit-Saint.

2°) Deux cent douze

Lettres très-intéressantes.

3°) Son Testament,

dont il a été parlé dans sa vie.

4°) Des Poèmes, les

uns théologiques, à savoir : trente-huit pièces dogmatico-bibliques et

quarante pièces morales : les autres historiques, dont

quatre-vingt-dix-sept se rapportent à saint Grégoire lui-même, deux cent

trente-et-une à d’autres personnages, cent vingt-neuf épitaphes et

quatre-vingt-dix-neuf épigrammes.

Dans le poème 131, le

saint docteur reconnaît qu’il fut redevable de sa naissance aux prières de sa

mère, et que, étant tombé dangereusement malade, il recouvra la santé par

la sainte table ; c’est-à-dire par le sacrifice de l’autel.

Il enseigne et pratique,

en plusieurs endroits de ses ouvrages, l’invocation des Saints. Il rapporte, or.

18, que sainte Justine demanda, par l’intercession de la Mère de Dieu, d’être

délivrée du danger auquel sa pureté était exposée. Selon lui, les âmes des

Saints connaissent dans le sein de la gloire ce qui nous concerne, ép.

201. Il dit, en parlant de saint Athanase, or. 24, « qu’il voit nos

besoins du haut du ciel, qu’il tend les bras à ceux qui combattent encore pour

la vertu, et qu’il s’intéresse d’autant plus en leur faveur, qu’il est

affranchi des liens du corps »·

Il conjure saint

Basile, 0r. 20, d’intercéder dans le ciel pour ceux qu’il avait gouvernés

et aimés sur la terre. Ailleurs, or. 18, il prie saint Cyprien de

l’assister. Il reproche à Julien son aversion pour les martyrs dont on

célébrait les fêtes, et le refus qu’il faisait d’honorer leurs corps, qui

chassaient les démons et guérissaient les malades. On voit que, de son temps,

il s’opérait plusieurs miracles par la vertu des cendres de saint Cyprien.

« Ceux », dit-il, or. 18,

« qui l’ont éprouvé, l’attestent hautement ».

De là, ce zèle avec

lequel il s’éleva contre les païens, qui, sous Julien l’Apostat, brûlaient les

tombeaux des martyrs et jetaient leurs reliques au vent, afin de les priver de

l’honneur qu’on leur rendait, or. 4. Julien lui-même, Misopog.,

reproche aux chrétiens de n’avoir employé, durant la persécution de sept mois

qu’ils souffrirent à Antioche, d’autres moyens pour se défendre, que la

dévotion des vieilles femmes qu’ils envoyaient prier assidûment devant les tombeaux

des martyrs.

Odiosam islam severitatem

septimum jam mensem perpessi, vota quidem et preces, quo tantis malis

enperemur, ad vetulas dimisimus quae circum seputera mortuorum assidue

versantur.

Tous les passages de

saint Grégoire, que nous venons de rapporter, ont fait dire au ministre Lailliée, de

cultu relig., que ce saint docteur avait contribué par ses paroles et ses

exemples à accréditer et à étendre le culte des Saints.

Si le style de saint

Grégoire de Nazianze a moins de douceur et de facilité que celui de saint

Basile, il est certainement plus fleuri et plus majestueux. Ce Père conçoit

toujours les choses noblement, et il les exprime avec une délicatesse et une

élégance inimitables.

Selon quelques auteurs,

saint Grégoire est le plus grand des orateurs tant sacrés que profanes. Saint

Basile partage cette gloire avec lui, au jugement de Dupin et de plusieurs

autres es savants. Le seul défaut qu’on puisse lui reprocher, c’est de

présenter à ses lecteurs trop de beautés, et de faire peut-être un usage

excessif des fleurs et des figures.

Ses vers sont dignes

d’Homère, pleins de douceur et de facilité ; on y trouve une sublimité qui leur

assure la préférence sur toutes les productions du même genre qui sont sorties

de la plume des écrivains ecclésiastiques. Ils mériteraient bien d’être lus dans

les écoles publiques.

Le cardinal Mai a

retrouvé sur les poésies de saint Grégoire de précieux commentaires, par Cosme,

précepteur de saint Jean Damascène, et plus tard évêque de Mazume ou Athédon,

dans le patriarcat d’Alexandrie.

SOURCE : https://www.laviedessaints.com/saint-gregoire-de-nazianze/

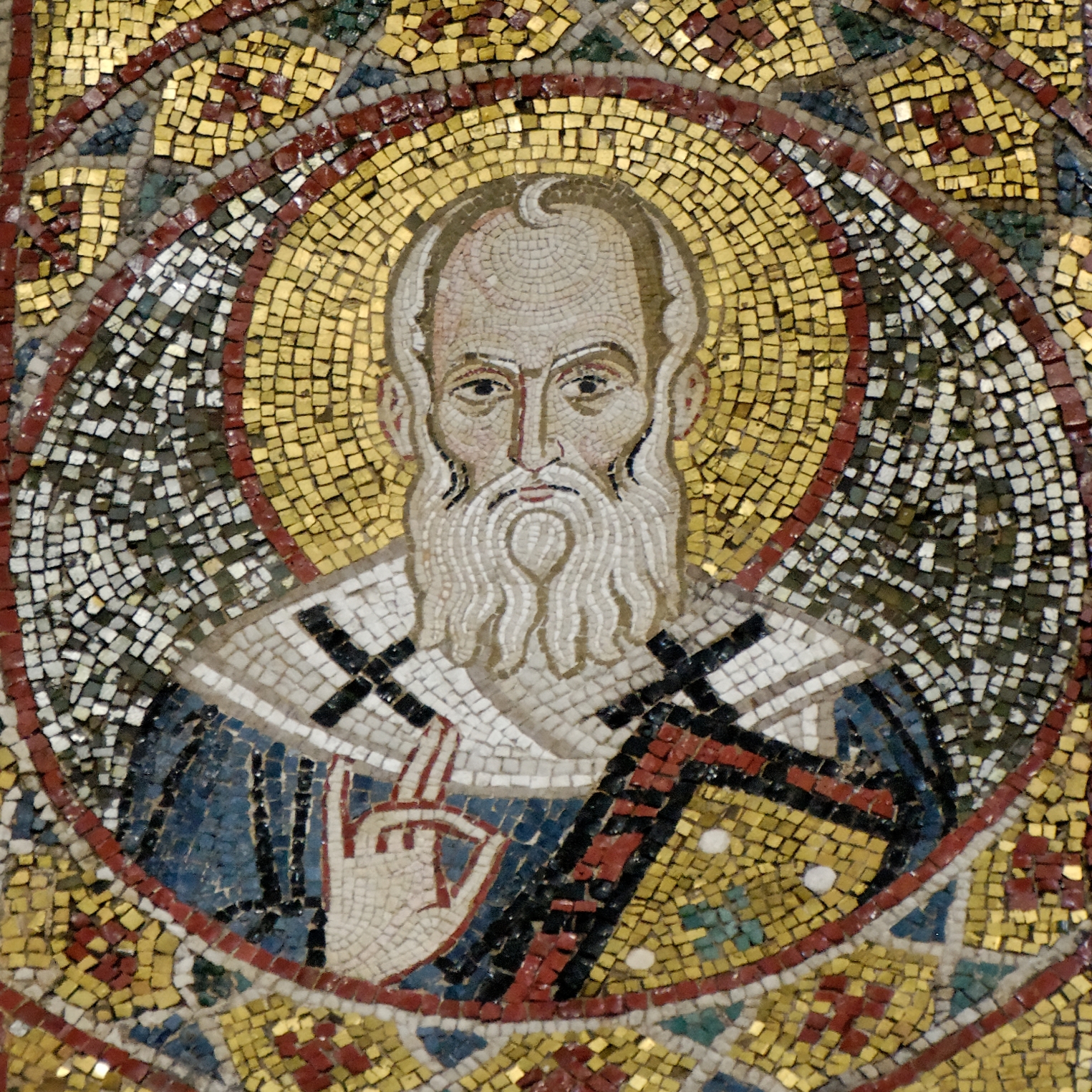

Fethiye

Camii, parekklesion, diakonikon, mosaics, Istanbul, Turkey - Apse conch, St.

Gregory the Theologian

St Grégoire de Nazianze,

évêque, confesseur et docteur

Mort le 25 janvier 379/380. Les Byzantins font mémoire de lui ce jour là. Les

martyrologes occidentaux le mentionnent au 9 mai. Sa fête se répandit au XVIe

siècle.

St Pie V en fit une fête double.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Quatrième leçon.

Grégoire, noble Cappadocien, qui fut surnommé le Théologien à cause de sa

science profonde des lettres divines, naquit à Nazianze, dans la Cappadoce.

Instruit à Athènes dans toutes sortes de sciences, en même temps que saint

Basile le Grand, il s’appliqua ensuite à l’étude de l’Écriture sainte. Les deux

amis s’y exercèrent durant quelques années dans un monastère, ayant pour

méthode d’interpréter les livres sacrés, non selon les lumières de leur esprit

propre, mais selon le raisonnement et l’autorité des anciens. Tandis qu’ils

florissaient par leur science et la sainteté de leur vie, ils furent appelés à

la charge de prêcher la vérité évangélique, et enfantèrent à Jésus-Christ un

grand nombre d’âmes.

Cinquième leçon.

Grégoire, étant retourné chez lui, fut d’abord créé Évêque de Sasime ; il

administra ensuite l’Église de Nazianze. Appelé plus tard à Constantinople pour

en gouverner l’Église, il purgea cette ville des hérésies dont elle était

infectée, et la ramena à la foi catholique ; mais son zèle, qui aurait dû lui

concilier la profonde affection de tous, lui attira l’envie d’un grand nombre.

Un grave dissentiment s’étant élevé à son sujet entre les Évêques, il renonça

spontanément à l’épiscopat, s’appliquant ces paroles d’un Prophète : « Si c’est

à cause de moi que cette tempête s’est élevée, jetez-moi dans la mer, afin que

vous cessiez d’être agités par l’orage ». Grégoire revint donc à Nazianze, et

ayant fait donner le gouvernement de cette Église à Eulalius, il se livra tout

entier à la contemplation des choses divines et à la composition d’ouvrages

théologiques.

Sixième leçon. Il écrivit

beaucoup, et en prose, et en vers, avec une piété et une éloquence admirables ;

il a mérité cet éloge, au jugement d’hommes doctes et saints, que l’on ne

trouve dans ses écrits rien qui ne soit conforme aux règles de la vraie piété et

de la foi catholique, rien qui puisse être contesté raisonnablement. Il fut le

ferme et zélé défenseur de la consubstantialité du Fils. De même qu’il n’était

inférieur à personne pour la sainteté de sa vie, il surpassait tous les autres

par la gravité de son style. Occupé à la lecture, l’étude et fa composition, il

vécut dans la solitude de la campagne à la manière d’un moine ; enfin, accablé

de vieillesse, il passa à ta vie bienheureuse du ciel, sous l’empire de

Théodose.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Aux côtés d’Athanase, un

second Docteur de l’Église se présente pour faire hommage de son génie et de

son éloquence à Jésus ressuscité. C’est Grégoire de Nazianze, l’ami et l’émule

de Basile, l’orateur insigne, le poète qui, dans la plus étonnante fécondité, a

su joindre l’énergie à l’élégance ; celui qui entre tous les Grégoires a mérité

et obtenu le grand nom de Théologien par la sûreté de sa doctrine, l’élévation

de s’a pensée, la, splendeur de son exposition. La sainte Église le voit avec

bonheur étinceler en ces jours sur le Cycle ; car nul n’a parlé avec plus de

magnificence que lui du mystère de la Pâque. On en peut juger par le début de

son deuxième discours pour cette auguste solennité. Écoutons.

« Je me tiendrai en

observation comme la sentinelle », nous dit l’admirable prophète Habacuc ; et

mot aujourd’hui, à son exemple, éclairé par l’Esprit-Saint, je fais aussi le

guet, j’observe le spectacle qui se découvre à moi, j’écoute les paroles qui

vont retentir. Et tandis que debout je considère, je vois assis sur les nuées

un personnage dont les traits sont ceux d’un Ange, et dont le vêtement est

éblouissant comme l’éclair. Sa voix retentit comme la trompette, et les rangs

pressés de l’armée céleste l’environnent ; et il dit : « Ce jour est le jour du

salut pour le monde visible et pour le monde invisible. Le Christ se lève

d’entre les morts, vous aussi levez-vous. Le Christ reprend possession de

lui-même, imitez-le. Le Christ s’élance du sépulcre, arrachez-vous aux liens du

péché. Les portes de l’enfer sont ouvertes, la mort est écrasée, le vieil Adam

est anéanti, et un autre lui est substitué : vous qui faites partie de la

création nouvelle dans le Christ, soyez renouvelés. »

« C’est ainsi qu’il

parlait, et les autres Anges répétaient ce qu’ils chantèrent au jour où le

Christ nous apparut dans sa naissance terrestre : Gloire à Dieu au plus haut

des deux, et sur la terre paix aux hommes de bonne volonté ! A moi maintenant

de parler sur toutes ces merveilles : que n’ai-je la voix des Anges, une voix capable

de retentir jusqu’aux confins de la terre !

« La Pâque du Seigneur !

La Pâque ! Encore la Pâque, en l’honneur de la Trinité ! C’est la fête des

fêtes, la solennité des solennités, qui l’emporte sur toutes les autres autant

que le soleil sur les étoiles. Dès hier combien fut auguste la journée, avec ses

robes blanches et ses nombreux néophytes portant des flambeaux ! Nous avions

double Fonction, publique et particulière ; toutes les classes d’hommes, des

magistrats et des dignitaires en grand nombre, dans cette nuit illuminée de

mille feux ; mais aujourd’hui combien ces allégresses et ces grandeurs sont

dépassées ! Hier n’était que l’aurore de la grande lumière qui s’est levée

aujourd’hui ; la joie que l’on ressentait n’était qu’un prélude de celle que

l’on éprouve en ce moment ; car en ce jour c’est la résurrection elle-même que

nous célébrons, non plus seulement espérée, mais accomplie, et s’étendant au

monde entier [1]. »

Ainsi préludait à la

harangue sacrée le sublime orateur, le poète divin qui ne fit que passer sur le

siège de Constantinople. Homme de retraite et de contemplation, les agitations

du siècle usèrent vite son courage ; la bassesse et la méchanceté des hommes

froissèrent son noble cœur ; et laissant à un autre le dangereux honneur

d’occuper un trône si disputé, il s’envola de nouveau vers sa chère solitude,

où il aimait tant à goûter Dieu et les saintes lettres. Il avait pu, dans son

rapide passage, malgré tant de traverses, raffermir pour longtemps la foi

ébranlée dans la capitale de l’empire, et tracer un sillon de lumière qui n’était

pas effacé, lorsque Jean Chrysostome vint s’asseoir sur cette chaire de Byzance

où tant d’épreuves l’attendaient à son tour.

L’Église grecque, dans

ses Menées, consacre à la mémoire de saint Grégoire de Nazianze les plus

magnifiques éloges. Nous en empruntons quelques traits.

(die xxv januarii.)

Célébrons par nos louanges le prince des pontifes, le grand docteur de l’Église

du Christ, celui dont la voix est semblable au plus riche concert, à la harpe

la plus mélodieuse, à la lyre la plus habile et la plus suave. Disons-lui :

Salut, ô abîme de la grâce divine ! Salut, docteur aux pensées sublimes et

célestes, Grégoire, Père des Pères ! Par quels hymnes et quels cantiques

pourrons-nous te célébrer, nomme égal aux Anges, toi qui as vécu sur la terre

au-dessus de l’humanité ? Tu fus le héraut de la divine parole, l’ami de la

chaste Vierge, le compagnon des Apôtres sur leur trône, l’honneur des martyrs

et des saints, l’adorateur de l’éternelle Trinité, ô pontife très saint.

Fidèles rassemblés pour

sa fête, célébrons dans nos chants spirituels le prince des pontifes, la gloire

des patriarches, l’interprète des plus profonds enseignements du Christ,

l’intelligence la plus sublime. Disons-lui : Salut, source de la théologie,

fleuve de la sagesse, initiateur aux connaissances divines ! Salut, astre

lumineux qui éclaires le monde entier par ta doctrine ! Salut, ô puissant

défenseur de la piété, adversaire généreux de l’impiété.

Tu as su éviter dans ta

sagesse les périls et les embûches de la chair, ô Grégoire notre père ; sur un

char conduit par les quatre vertus, tu es monté par le milieu du ciel, et tu

t’es envolé vers l’ineffable beauté. Elle t’enivre maintenant de délices, et tu

implores pour nos âmes la miséricorde et la paix.

Ouvrant ta bouche à la

parole de Dieu, tu as attiré l’Esprit de sagesse, et rempli de la grâce, tu as

fait retentir les dogmes divins, ô Grégoire trois fois heureux ! Placé aux

rangs des Puissances angéliques, tu as prêché la triple et indivisible Lumière

; éclairés par ta divine doctrine, nous adorons la Trinité, nous confessons en

elle une seule divinité, afin d’obtenir le salut de nos âmes !

O Grégoire inspiré de

Dieu, ta langue enflammée a consumé les formules captieuses des hérétiques

ennemis du Seigneur. Tu as paru comme une bouche divine, exposant dans

l’Esprit-Saint les grandeurs de Dieu ; dans tes écrits tu nous as manifesté la

puissance et la substance même de la Trinité mystérieuse et impénétrable. Comme

un triple soleil tu as éclairé ce monde terrestre ; et maintenant tu intercèdes

sans relâche pour nos âmes.

Salut, ô fleuve de Dieu,

toujours rempli des eaux de la grâce ! Tu baignes la cité du Christ roi, et tu

la réjouis par ta parole et tes enseignements divins : torrent de délices, mer

sans fond, gardien fidèle et juste de la doctrine, défenseur courageux de la

Trinité, organe de l’Esprit-Saint, génie attentif et vigilant, langue

harmonieuse , interprète des mystères les plus profonds de l’Écriture, supplie

maintenant le Christ de répandre sur nous s’a grande miséricorde.

Tu t’es élevé sur la

montagne des vertus, ayant abdiqué les choses de la terre, étant devenu

étranger aux œuvres de mort ; tu as reçu les tables écrites de la main de Dieu,

et le dogme de ta très pure théologie, et tu nous enseignes les mystères célestes,

ô Grégoire rempli ’de sagesse.

La Sagesse de Dieu a eu

ton amour, tu as recherché la beauté de sa parole, et tu l’as estimée au-dessus

de tout ce qui charme les hommes sur la terre ; c’est pourquoi le Seigneur a

orné ta tête d’une couronne de grâces, ô Bienheureux, et t’ayant mis à part, il

t’a choisi pour être le Théologien.

Afin que ton âme

s’éclairât tout entière des rayons de l’auguste Trinité , tu l’as polie, ô

Père, la rendant sans tache par ta noble profession de toutes les vertus, et

semblable à un miroir nouveau et préparé avec le plus grand soin ; alors la

réfraction du divin éclat t’a fait paraître semblable à un Dieu.

Tu as paru comme un

nouveau Samuel donné de Dieu ; avant d’être conçu tu fus donné à Dieu, ô

bienheureux ! La prudence et la continence ont été ta parure, et, orné de la

robe sacrée des pontifes, tu as été établi, ô Père, comme le médiateur entre le

Créateur et la créature.

Tu as approché tes lèvres

vénérables de la coupe qui contient la sagesse, ô Grégoire notre père ! tu as

aspiré les eaux divines de la théologie, et tu les as fait couler avec

abondance sur les fidèles ; tu as arrêté le torrent pernicieux de l’hérésie, ce

torrent qui roule le blasphème. L’Esprit-Saint a trouvé en toi un pasteur

gouvernant avec sainteté, repoussant et soulevant contre lui les audacieuses

fureurs des impies, semblables aux violents orages des vents sur la mer ; un

pasteur prêchant la Trinité dans l’unité de substance.

Brebis de la sainte

Église, célébrons dans nos divins cantiques la lyre de l’Esprit-Saint, la faux

des hérésies, les délices des orthodoxes, un second disciple reposant sur la

poitrine de Jésus, le contemplateur du Verbe, le patriarche rempli de sagesse.

Disons-lui : Tu es un bon pasteur, ô Grégoire ! tu t’es livré pour nous, comme

le Christ notre maître, et maintenant tu tressailles d’allégresse avec Paul, et

tu intercèdes pour nos âmes.

Nous vous saluons, ô

Grégoire, docteur immortel, vous à qui l’Orient et l’Occident ont décerné de

concert le titre de Théologien par excellence ! Illuminé des rayons de la

glorieuse Trinité, vous nous en avez manifesté les splendeurs, autant que notre

œil mortel les peut entrevoir à travers le nuage de cette vie. En vous s’est

accomplie cette parole : « Heureux ceux qui ont le cœur pur, parce qu’ils

verront Dieu [2] ! » La pureté de votre âme l’avait préparée à recevoir la

lumière divine, et votre plume inspirée a su rendre une partie de ce que votre

âme avait goûté. Obtenez-nous, ô grand Docteur, le don de la foi, qui met la

créature en rapport avec Dieu, et le don de l’intelligence, qui lui fait

entendre ce qu’elle croit. Tous vos labeurs eurent pour but de prémunir les

fidèles contre les séductions de l’hérésie, en faisant luire à leurs yeux les

dogmes divins dans toute leur magnificence ; rendez-nous attentifs, afin que

nous évitions les pièges de Terreur, et ouvrez notre œil à la lumière ineffable

des mystères, à cette lumière qui, comme dit saint Pierre, est pour nous «

semblable à une lampe « allumée dans un lieu obscur, jusqu’à ce que le « jour

commence à briller, et que l’étoile du ma- »tin se lève dans nos cœurs [3] ».

En ces temps où l’Orient,

si longtemps en proie à la triste immobilité de l’erreur séculaire et de la

servitude, semble à la veille d’une crise qui doit modifier profondément ses

destinées, tandis qu’une politique profane songe à exploiter au profit de

l’ambition humaine les changements qui se préparent, souvenez-vous, ô Grégoire,

de l’infortunée Byzance. Demain peut-être les puissances du monde se la

disputeront comme une proie. O vous qui fûtes un moment son pasteur, vous dont

le souvenir n’est pas encore effacé de sa mémoire, arrachez-la à l’esprit de

schisme et d’erreur. Elle n’est tombée sous le joug de l’infidèle qu’en

punition de sa révolte contre le vicaire du Christ. Bientôt ce joug sera brisé

; obtenez, ô Grégoire, qu’en même temps celui de l’erreur et du schisme, plus

dangereux et plus humiliant encore, se rompe et soit anéanti pour jamais. Déjà

un mouvement de retour se manifeste ; des provinces entières s’ébranlent et

semblent vouloir jeter un regard d’espérance vers la mère commune des Églises,

qui leur ouvre ses bras. O Grégoire ! Du haut du ciel, aidez à la

réconciliation. L’Orient et l’Occident vous honorent comme l’un des plus

sublimes organes de la vérité divine ; par vos prières, obtenez que l’Orient et

l’Occident soient encore une fois réunis dans un même bercail, sous un même

pasteur, avant que l’Agneau immolé et ressuscité d’entre les morts redescende

du ciel pour séparer l’ivraie du bon grain, et pour emmener avec lui dans sa

gloire l’Église son épouse et notre mère, hors du sein de laquelle il n’y a pas

de salut.

Aidez-nous, en ces jours,

à contempler les grandeurs de notre divin Ressuscité ; faites-nous tressaillir

d’un saint enthousiasme dans cette Pâque qui vous inondait de ses joies, et

vous inspirait les sublimes accents que nous venons d’entendre. Ce Christ,

sorti triomphant du tombeau, vous l’avez aimé dès vos plus tendres années, et

dans votre vieillesse son amour faisait encore battre votre cœur. Priez, afin

que, nous aussi, nous lui demeurions fidèles, que ses divins mystères ravissent

toujours nos âmes, que cette Pâque demeure toujours en nous, que le

renouvellement qu’elle nous a apporté persévère dans notre vie, qu’à ses

retours successifs elle nous retrouve attentifs et vigilants pour l’accueillir

avec une ardeur toute nouvelle, jusqu’à ce que la Pâque éternelle nous

accueille et nous ouvre ses allégresses sans fin.

[1] Oratio II in sanctum

Pascha.

[2] Matth. v, 8.

[3] II Petr. I, 19.

Grzegorz

z Nazjanzu na ambonie z 1693 wyrzeźbiony przez Jana Krzysztofa Doebel w

Królewcu. W bazylice w Dobrym Mieście

Part of the pulpit sculpted by Jan Krzysztof Doebel in Koenigsberg.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Grégoire le Théologien,

comme l’appellent les Grecs à cause de l’excellence de son génie, avait une âme

douce et une nature éminemment poétique ; à l’humilité et à l’amour de la paix

il sacrifia la chaire même de Constantinople pour se retirer à la campagne et y

mener une vie de moine. Sa fête ne fut pas introduite dans le calendrier avant

1505, quand les études des humanistes et la culture grecque de la Renaissance

firent mieux apprécier ses mérites. La messe est entièrement du Commun des

Docteurs, avec l’épître Iustus qui s’adapte mieux au caractère mystique du

Saint.

Si, en effet, luttant et

souffrant avec une énergique constance, il arriva, au bout de quelques années,

à ramener la ville de Constantinople à la foi de Nicée, ce fut entièrement

l’œuvre de son zèle vraiment divin, car, par nature, Grégoire était l’homme qui

avait le plus horreur des positions difficiles et des luttes. Il le montra bien

quand, créé contre sa volonté évoque de Sasime par saint Basile, il ne sut pas

s’adapter à cette charge difficile et, après quelque temps, revint dans sa

patrie. La passion de Grégoire était la vie contemplative et la discipline

monastique, à laquelle il demeura fermement attaché jusqu’à la fin de ses jours

(+ 389 ou 390). Pour faire connaître aux lecteurs le genre du génie de saint

Grégoire de Nazianze, voici sa biographie faite par lui-même :

EPITAPHION (Carm. XXX)

CVR • CARNEIS • LAQVEIS •

TV • ME • PATER • IMPLICVISTI ?

CVR • SVBSVM • VITAE •

HVIC • QVAE • MIHI • BELLA • MOVET

DIVINO • PATRE • SVM •

GENITVS • SANCTAQVE • PARENTE

HAEC • MIHI • LVX • VITAE

• NAMQVE • PRECANTE • DATA • EST

ORAVIT • SVMMOQVE • DEO •

ME • VOVIT • ET • ORTVS

EST • MIHI • PER • SOMNVM

• VIRGINITATIS • AMOR

ISTA • QVIDEM • CHRISTI •

POST • AT • SVBIERE • PROCELLAE

RAPTA • MIHI • BONA •

SVNT • FRACTA - DOLORE • CARO

PASTORES • SENSI • QVALES

• VIX • CREDERET • VLLVS

ORBATVSQUE • ABII • PROLE

• MALISQVE • GRAVIS

GREGORII • HAEC • VITA •

EST • AT • CHRISTI • POSTERA • CVRAE

QVI • VITAE - DATOR • EST

• EXPRIMAT • ISTA • LAPIS

Pourquoi, ô divin Père,

me trouve-je embarrassé dans les lacs de la chair ? Pourquoi suis-je contraint

de supporter cette vie qui fait la guerre à mon esprit ? Je naquis d’un père

qui fut pourtant un saint évêque, et vertueuse fut aussi ma mère, aux prières

de qui je dus de venir au monde. Celle-ci me consacra aussitôt à Dieu, et, dans

une vision nocturne, l’amour de la virginité me fut inspiré. Jusqu’ici tout fut

don du Christ. Survinrent ensuite les luttes, je fus privé de mes biens, et la

douleur brisa mon corps. J’eus à connaître de tels pasteurs qu’on ne pourrait

pas même en imaginer d’autres ; mais je m’en allai (de Constantinople) privé de

mes enfants, et accablé de peine. Telle a été jusqu’à présent la vie de

Grégoire. De l’avenir, que le Christ, qui donne la vie, prenne soin. A cette

pierre d’exprimer ces choses.

On dit qu’un ancien

oratoire, près du monastère de Sainte-Marie in Campa Marzio, était consacré, à

Rome, à la mémoire de saint Grégoire de Nazianze. Bien plus, la tradition

locale des moniales voulait que celles-ci, venant de Constantinople à Rome au

temps du pape Zacharie, eussent apporté avec elles et déposé en ce lieu le

corps du saint docteur, à qui elles auraient pour cette raison dédié

l’oratoire. Cette assertion n’est cependant pas très acceptable, car, dans la

biographie de Léon III, le Liber Pontificalis fait déjà mention de quelques

dons offerts in oratorio sancti Gregorii quod ponitur in Campo Martis [4] ;

nous savons d’autre part que les reliques de saint Grégoire de Nazianze furent

transférées de la Cappadoce à la basilique des Apôtres à Constantinople seulement

vers le milieu du Xe siècle, alors que les moniales s’étaient établies dans

l’antique Champ-de-Mars à Rome depuis deux cents ans au moins.

[4] Lib. Pontif. Ed.

Duchesne, II, p. 25.

Гомилии

Григория Богослова gr. 510, f 915

Homilies

of Gregory the Theologian gr. 510, f 915

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

La sainte amitié.

Saint Grégoire. — Jour de

mort : 9 mai 390. Tombeau : Au Xe siècle, son corps fut transporté dans

l’Apostoleion, à Constantinople. Vie : Grégoire le Théologien (c’est ainsi que

les Grecs le nomment) naquit en 329. à Nazianze, en Cappadoce. Il fut une des «

trois lumières » de Cappadoce. Sa mère, sainte Nonna, posa les assises de sa

sainteté future. Pour sa formation intellectuelle, il visita les écoles les

plus célèbres de son temps, celles de Césarée, d’Alexandrie et d’Athènes. Dans

cette dernière ville, il noua avec saint Basile une amitié devenue historique.

En 381, il célébrait encore cette amitié avec un enthousiasme juvénile. En 360,

il reçut le baptême et vécut ensuite pendant quelque temps dans la solitude. En

372, il reçut la consécration épiscopale des mains de saint Basile. Son père,

Grégoire, évêque de Nazianze, insista pour qu’il l’aidât dans le ministère des

âmes. En 379, il fut appelé au siège de Constantinople. Mais, en raison des

nombreuses difficultés qu’il rencontra, il retourna à la solitude tant désirée.

Il se consacra entièrement à la vie contemplative. Sa vie se caractérise par

une alternance entre la vie contemplative et le ministère des âmes. Tous nos

désirs vont vers la solitude, mais les besoins du temps le rappellent sans cesse

à la vie active ; il doit prendre part au mouvement religieux d’alors. Ce qui

lui valut ses succès, ce fut son éloquence entraînante. Il fut, sans conteste,

l’un des meilleurs orateurs de l’antiquité chrétienne. Ses écrits lui ont valu

le titre d’honneur de docteur de l’Église.

Pratique : Nous devons,

nous aussi, concilier harmonieusement les deux aspects de la vie religieuse ;

la vie de piété et de contemplation qui recherche la solitude, et la vie

active, adonnée à la charité et au zèle des âmes, qui convient aux besoins de notre

temps. La messe est tirée du commun des docteurs (In medio). Saint Grégoire est

vraiment « la lumière placée sur le chandelier, qui brille pour tous ceux qui

sont dans la maison (l’Église) » (Évangile). Il fut rempli de « l’Esprit de

sagesse et de science » (Int. Ép.). La leçon (Justus) convient : mieux au

caractère contemplatif du saint que celle du commun.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/09-05-St-Gregoire-de-Nazianze

Meister

der Predigten des Heiligen Gregor von Nazianz. Sammlung der Predigten des Hl.

Gregor von Nazianz, Szene: Vision des Ezechiel (Bibliothèque nationale de

France MS Grc 510, folio 438v), vers 880, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

« Les cinq discours sur

Dieu » de saint Grégoire

Charles

Rouvier | 22 novembre 2016

La foi chrétienne est

souvent éprouvée. A tel point que la connaissance même des dogmes a beaucoup

reflué parmi les catholiques mêmes. Mais un secours nous vient des premiers

âges : saint Grégoire de Naziance (329-390) et ses Cinq Discours sur Dieu.

Une manière de renforcer les chrétiens sur le cœur même de leur foi : Dieu en

personne.

Une œuvre de combat sur

un thème crucial. Dits aussi « discours théologiques », les Cinq

Discours sur Dieu de saint Grégoire de Naziance sont une réponse aux hérésies

triomphantes du IVe siècle (marcionisme, arianisme, apollinarisme etc…) dont

certaines reviennent d’ailleurs sous d’autres noms, à la faveur du vide laissé

par la déchristianisation. Le grand mérite des cinq discours est de

d’éclairer et renforcer les chrétiens sur le cœur, sur l’objet même de leur

foi : Dieu en personne. Cinq discours seront consacrés à ce problème dont

l’importance est parfois oubliée et pourtant, c’est le cas de le dire,

cruciale.

Une initiation aux

mystères du Créateur

Pour cela, il procèdera

avec une méthode qu’il décrit lui-même, selon laquelle « tout exposé

comporte deux parties : une ou l’on établit ses idées, une autre où l’on

réfute ses adversaires ». Le chemin est donc clair, les discours sont une

invitation à découvrir d’abord la Vérité nette et pure, ensuite de comprendre

pourquoi elle est bel et bien la Vérité malgré les objections qui peuvent être

formulée.

Lire aussi :

Méditations

de l’Avent : « Le Dieu vivant est la Trinité vivante »

Ainsi détaillera-t-il