Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664),

Saint Francis of Assisi, circa 1658, oil

on canvas, 64 x 53, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Saint François d'Assise

Fondateur de l'Ordre des

Frères Mineurs (+ 1226)

Né à Assise au foyer de

Pierre Bernardone et de Dame Pica, François vit d'abord une jeunesse folle.

Participant à la guerre entre Assise et Pérouse, il est fait prisonnier.

Plus tard, parti pour une

autre guerre, il entend une voix lui dire: "Pourquoi sers-tu le serviteur

et non le maître?"

C'est pour lui le début

d'une nouvelle existence. Rentré à Assise, "le roi de la jeunesse" se

tourne vers les pauvres et les lépreux.

Il a 24 ans. Dans la

chapelle de Saint Damien, il entend le grand crucifix lui dire: "Répare ma

maison qui, tu le vois, tombe en ruines."

Le voilà transformé en

maçon. Pour réparer la chapelle, il dépense l'argent de son père qui l'assigne

devant l'Évêque.

Il se dépouille alors de

tous ses vêtements en déclarant qu'il n'a d'autre père que celui qui est aux

Cieux.

Un matin, il entend

l'évangile de l'envoi en mission des disciples. Appliquant l'Évangile à la

lettre, il parcourt la campagne, pieds nus et une corde pour ceinture, en annonçant:

"Que Le Seigneur vous donne sa Paix."

Des compagnons lui

viennent et il leur rédige une Règle faite de passages d'Évangile. Quand ils

seront douze, ils iront à Rome la faire approuver par le Pape Innocent III.

Parallèlement, Claire

Favarone devient la première Clarisse.

Pour les laïcs, il fonde

un troisième Ordre, appelé aujourd'hui "la Fraternité séculière." Il

envoie ses Frères de par le monde et lui-même rencontre le sultan à Damiette

pour faire cesser la guerre entre Chrétiens et Musulmans.

A son retour, il trouve

l'Ordre en grandes difficultés d'unité. Il rédige une nouvelle Règle et se

retire, épuisé, sur le mont Alverne où il reçoit les stigmates du Christ en

Croix.

Il connaît ainsi dans son

cœur l'infini de l'Amour du Christ donnant sa vie pour les hommes. En 1226, au

milieu de très grandes souffrances, il compose son "Cantique des

Créatures" et le 3 octobre, "nu, sur la terre nue", il accueille

"notre sœur la mort corporelle."

Ce cantique a été composé

par François d’Assise deux ans avant sa mort et achevé par Frère Pacifique.

Saint François d'Assise

est le patron de tous les louveteaux.

Savez-vous

pourquoi ? C'est à cause d'un épisode de sa vie : le loup de Gubbio.

La figure du Saint

italien évoque un art de vivre et une manière d'être Chrétien.

Le Pape Grégoire IX l'a

Canonisé en 1228. Amoureux de la nature, Jean Paul II l'a fait patron de

l'écologie en 1979.

Il inspire aussi les

non-violents. (Église

catholique en France)

Prière de Saint François

d'Assise: Seigneur,

fais de moi un instrument de ta paix...

"Jean-Paul II, en

1979, un an après son accession au pontificat, évoque la volonté du Créateur de

voir l'homme être en communion avec la nature et non en position d'exploiteur

ou de destructeur.

Il désigne Saint François

d'Assise comme patron des écologistes, sorte de Bénédiction à une époque où on

les regardait souvent de travers." (Source: la

sauvegarde de la création - Église catholique en France)

Le 4 Octobre, mémoire de

Saint François d’Assise. Après une jeunesse légère, il choisit de vivre selon

l’Évangile, en servant le Christ, découvert principalement dans les pauvres et

les abandonnés, et en se faisant pauvre lui-même.

Il attira à lui et

rassembla des compagnons, les Frères Mineurs. Sur les routes, jusqu’en Terre

sainte, il prêcha à tous l’Amour de Dieu, cherchant par sa parole et ses gestes

à suivre le mieux possible Le Christ, et voulut mourir sur la terre nue, en

1226.

Martyrologe romain

Loué sois-tu, mon

Seigneur, avec toutes tes créatures, spécialement messire frère Soleil, par qui

tu nous donnes le jour, la lumière ; il est beau, rayonnant d’une grande

splendeur, et de toi, le Très-Haut, il nous offre le symbole

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/800/Saint-Francois-d-Assise.html

Cimabue (1240–1302), Madonna Enthroned with the Child, Saint Francis and Four Angels, circa 1278, 320 x 340, Lower Basilica of San Francesco

Cimabue (1240–1302),

Madonna Enthroned with the Child, Saint Francis and Four Angels, circa 1278, 320 x

340, Lower

Basilica of San Francesco

Saint François d'Assise

Fondateur

(1182-1226)

La vie de saint François

d'Assise est la condamnation des sages du monde, qui regardent comme un

scandale et une folie l'humilité de la Croix. Il naquit à Assise, en Ombrie.

Comme ses parents, qui étaient marchands, faisaient beaucoup de commerce avec

les Français, ils lui firent apprendre la langue française et il parvint à la

parler si parfaitement, qu'on lui donna le nom de François, quoiqu'il eût reçu

celui de Jean au baptême.

Sa naissance avait été

marquée par une merveille: d'après un avis du Ciel, sa mère le mit au monde sur

la paille d'une étable. Dieu voulait qu'il fût, dès le premier moment,

l'imitateur de Celui qui eut pour berceau une crèche et est mort sur une Croix.

Les premières années de François se passèrent pourtant dans la dissipation; il

aimait la beauté des vêtements, recherchait l'éclat des fêtes, traitait comme

un prince ses compagnons, avait la passion de la grandeur; au milieu de ce

mouvement frivole, il conserva toujours sa chasteté.

Il avait une grande

compassion pour les pauvres. Ayant refusé un jour l'aumône à un malheureux, il

s'en repentit aussitôt et jura de ne plus refuser à quiconque lui demanderait

au nom de Dieu. Après des hésitations, François finit par comprendre la Volonté

de Dieu sur lui et se voua à la pratique de cette parole qu'il a réalisée plus

que tout autre Saint: "Si quelqu'un veut venir après Moi, qu'il se renonce

lui-même, qu'il porte sa Croix et qu'il Me suive!"

Sa conversion fut

accompagnée de plus d'un prodige: un crucifix lui adressa la parole; un peu

plus tard, il guérit plusieurs lépreux en baisant leurs plaies. Son père fit

une guerre acharnée à cette vocation extraordinaire, qui avait fait de son

fils, si plein d'espérance, un mendiant jugé fou par le monde. François se

dépouilla de tous ses vêtements, ne gardant qu'un cilice, et les remit à son

père en disant: "Désormais je pourrai dire avec plus de vérité:

"Notre Père, qui êtes aux Cieux."

Un jour, il entendit, à

l'Évangile de la Messe, ces paroles du Sauveur: "Ne portez ni or ni

argent, ni aucune monnaie dans votre bourse, ni sac, ni deux vêtements, ni

souliers, ni bâtons." Dès lors, il commença cette vie tout angélique et

tout apostolique dont il devait lever l'étendard sur le monde. On vit, à sa

parole, des foules se convertir; bientôt les disciples affluèrent sous sa

conduite; il fonda un Ordre de religieux qui porta son nom, et un Ordre de

religieuses qui porte le nom de sainte Claire, la digne imitatrice de François.

Ces deux frêles tiges devinrent des arbres immenses.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_francois_d_assise.html

Bonaventura Berlinghieri (1210–1287),

San Francesco e storie della sua

vita, tempera su tavola, 1235, 160 x 123, chiesa di San Francesco / Church of Saint Francis, Pescia

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 27 janvier 2010

Saint François d’Assise

Chers frères et sœurs,

Dans une récente

catéchèse, j'ai déjà illustré le rôle providentiel que l'Ordre des frères

mineurs et l'Ordre des frères prêcheurs, fondés respectivement par saint

François d'Assise et par saint Dominique Guzman, eurent dans le renouveau de

l'Eglise de leur temps. Je voudrais aujourd'hui vous présenter la figure de

François, un authentique « géant » de sainteté, qui continue à fasciner de très

nombreuses personnes de tous âges et de toutes religions.

« Surgit au monde un

soleil ». A travers ces paroles, dans la Divine Comédie (Paradis, chant XI), le

plus grand poète italien Dante Alighieri évoque la naissance de François,

survenue à la fin de 1181 ou au début de 1182, à Assise. Appartenant à une

riche famille – son père était marchand drapier –, François passa son

adolescence et sa jeunesse dans l'insouciance, cultivant les idéaux

chevaleresques de l'époque. A l'âge de vingt ans, il participa à une campagne

militaire, et fut fait prisonnier. Il tomba malade et fut libéré. De retour à

Assise, commença en lui un lent processus de conversion spirituelle, qui le

conduisit à abandonner progressivement le style de vie mondain qu'il avait mené

jusqu'alors. C'est à cette époque que remontent les célèbres épisodes de la

rencontre avec le lépreux, auquel François, descendu de cheval, donna le baiser

de la paix, et du message du Crucifié dans la petite église de saint Damien.

Par trois fois, le Christ en croix s'anima, et lui dit: « Va, François, et

répare mon église en ruine ». Ce simple événement de la parole du Seigneur

entendue dans l'église de Saint-Damien renferme un symbolisme profond.

Immédiatement, saint François est appelé à réparer cette petite église, mais

l'état de délabrement de cet édifice est le symbole de la situation dramatique

et préoccupante de l'Eglise elle-même à cette époque, avec une foi

superficielle qui ne forme ni ne transforme la vie, avec un clergé peu zélé,

avec un refroidissement de l'amour; une destruction intérieure de l'Eglise qui

comporte également une décomposition de l'unité, avec la naissance de

mouvements hérétiques. Toutefois, au centre de cette église en ruines se trouve

le crucifié, et il parle: il appelle au renouveau, appelle François à un

travail manuel pour réparer de façon concrète la petite église de Saint-Damien,

symbole de l'appel plus profond à renouveler l'Eglise même du Christ, avec la

radicalité de sa foi et l'enthousiasme de son amour pour le Christ. Cet

événement qui a probablement eu lieu en 1205, fait penser à un autre événement

semblable qui a eu lieu en 1207: le rêve du Pape Innocent III. Celui-ci voit en

rêve que la Basilique Saint-Jean-de-Latran, l'église mère de toutes les

églises, s'écroule et un religieux petit et insignifiant la soutient de ses

épaules afin qu'elle ne tombe pas. Il est intéressant de noter, d'une part, que

ce n'est pas le Pape qui apporte son aide afin que l'église ne s'écroule pas,

mais un religieux petit et insignifiant, dans lequel le Pape reconnaît François

qui lui rend visite. Innocent III était un Pape puissant, d'une grande culture

théologique, et d'un grand pouvoir politique, toutefois, ce n'est pas lui qui

renouvelle l'église, mais le religieux petit et insignifiant: c'est saint

François, appelé par Dieu. Mais d'autre part, il est intéressant de noter que

saint François ne renouvelle pas l'Eglise sans ou contre le Pape, mais

seulement en communion avec lui. Les deux réalités vont de pair: le Successeur

de Pierre, les évêques, l'Eglise fondée sur la succession des apôtres et le

charisme nouveau que l'Esprit Saint crée en ce moment pour renouveler l'Eglise.

C'est ensemble que se développe le véritable renouveau.

Retournons à la vie de

saint François. Etant donné que son père Bernardone lui reprochait sa

générosité exagérée envers les pauvres, François, devant l'évêque d'Assise, à

travers un geste symbolique, se dépouille de ses vêtements, montrant ainsi son

intention de renoncer à l'héritage paternel: comme au moment de la création,

François n'a rien, mais uniquement la vie que lui a donnée Dieu, entre les

mains duquel il se remet. Puis il vécut comme un ermite, jusqu'à ce que, en

1208, eut lieu un autre événement fondamental dans l'itinéraire de sa

conversion. En écoutant un passage de l'Evangile de Matthieu – le discours de

Jésus aux apôtres envoyés en mission –, François se sentit appelé à vivre dans

la pauvreté et à se consacrer à la prédication. D'autres compagnons

s'associèrent à lui, et en 1209, il se rendit à Rome, pour soumettre au Pape

Innocent III le projet d'une nouvelle forme de vie chrétienne. Il reçut un

accueil paternel de la part de ce grand Souverain Pontife, qui, illuminé par le

Seigneur, perçut l'origine divine du mouvement suscité par François. Le

Poverello d'Assise avait compris que tout charisme donné par l'Esprit Saint

doit être placé au service du Corps du Christ, qui est l'Eglise; c'est

pourquoi, il agit toujours en pleine communion avec l'autorité ecclésiastique.

Dans la vie des saints, il n'y a pas d'opposition entre charisme prophétique et

charisme de gouvernement, et si apparaissent des tensions, ils savent attendre

avec patience les temps de l'Esprit Saint.

En réalité, certains

historiens du XIXe siècle et même du siècle dernier ont essayé de créer

derrière le François de la tradition, un soi-disant François historique, de

même que l'on essaie de créer derrière le Jésus des Evangiles, un soi-disant

Jésus historique. Ce François historique n'aurait pas été un homme d'Eglise,

mais un homme lié immédiatement uniquement au Christ, un homme qui voulait

créer un renouveau du peuple de Dieu, sans formes canoniques et sans

hiérarchie. La vérité est que saint François a eu réellement une relation très

directe avec Jésus et avec la Parole de Dieu, qu'il voulait suivre sine glossa,

telle quelle, dans toute sa radicalité et sa vérité. Et il est aussi vrai

qu'initialement, il n'avait pas l'intention de créer un Ordre avec les formes

canoniques nécessaires, mais simplement, avec la parole de Dieu et la présence

du Seigneur, il voulait renouveler le peuple de Dieu, le convoquer de nouveau à

l'écoute de la parole et de l'obéissance verbale avec le Christ. En outre, il

savait que le Christ n'est jamais « mien », mais qu'il est toujours « nôtre »,

que le Christ, je ne peux pas l'avoir « moi » et reconstruire « moi » contre

l'Eglise, sa volonté et son enseignement, mais uniquement dans la communion de

l'Eglise construite sur la succession des Apôtres qui se renouvelle également

dans l'obéissance à la parole de Dieu.

Et il est également vrai

qu'il n'avait pas l'intention de créer un nouvel ordre, mais uniquement de

renouveler le peuple de Dieu pour le Seigneur qui vient. Mais il comprit avec

souffrance et avec douleur que tout doit avoir son ordre, que le droit de

l'Eglise lui aussi est nécessaire pour donner forme au renouveau et ainsi

réellement il s'inscrivit de manière totale, avec le cœur, dans la communion de

l'Eglise, avec le Pape et avec les évêques. Il savait toujours que le centre de

l'Eglise est l'Eucharistie, où le Corps du Christ et son Sang deviennent

présents. A travers le Sacerdoce, l'Eucharistie est l'Eglise. Là où le

Sacerdoce, le Christ et la communion de l'Eglise vont de pair, là seul habite

aussi la parole de Dieu. Le vrai François historique est le François de

l'Eglise et précisément de cette manière, il parle aussi aux non-croyants, aux

croyants d'autres confessions et religions.

François et ses frères,

toujours plus nombreux, s'établirent à la Portioncule, ou église Sainte-Marie

des Anges, lieu sacré par excellence de la spiritualité franciscaine. Claire

aussi, une jeune femme d'Assise, de famille noble, se mit à l'école de

François. Ainsi vit le jour le deuxième ordre franciscain, celui des Clarisses,

une autre expérience destinée à produire d'insignes fruits de sainteté dans

l'Eglise.

Le successeur d'Innocent III

lui aussi, le Pape Honorius III, avec sa bulle Cum dilecti de 1218 soutint le

développement singulier des premiers Frères mineurs, qui partaient ouvrir leurs

missions dans différents pays d'Europe, et jusqu'au Maroc. En 1219, François

obtint le permis d'aller s'entretenir, en Egypte, avec le sultan musulman,

Melek-el-Kâmel, pour prêcher là aussi l'Evangile de Jésus. Je souhaite

souligner cet épisode de la vie de saint François, qui est d'une grande

actualité. A une époque où était en cours un conflit entre le christianisme et

l'islam, François, qui n'était volontairement armé que de sa foi et de sa

douceur personnelle, parcourut concrètement la voie du dialogue. Les chroniques

nous parlent d'un accueil bienveillant et cordial reçu de la part du sultan musulman.

C'est un modèle dont devraient s'inspirer aujourd'hui encore les relations

entre chrétiens et musulmans: promouvoir un dialogue dans la vérité, dans le

respect réciproque et dans la compréhension mutuelle (cf. Nostra Aetate, n. 3).

Il semble ensuite que François ait visité la Terre Sainte, jetant ainsi une

semence qui porterait beaucoup de fruits: ses fils spirituels en effet firent

des Lieux où vécut Jésus un contexte privilégié de leur mission. Je pense

aujourd'hui avec gratitude aux grands mérites de la Custodie franciscaine de

Terre Sainte.

De retour en Italie,

François remit le gouvernement de l'ordre à son vicaire, le frère Pietro

Cattani, tandis que le Pape confia à la protection du cardinal Ugolino, le

futur Souverain Pontife Grégoire IX, l'Ordre, qui recueillait de plus en plus

d'adhésions. Pour sa part, son Fondateur, se consacrant tout entier à la

prédication qu'il menait avec un grand succès, rédigea la Règle, ensuite

approuvée par le Pape.

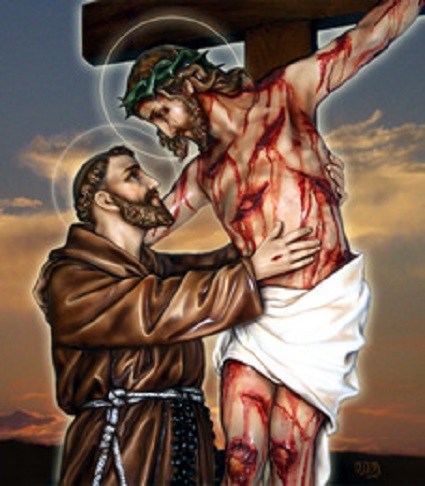

En 1224, dans l'ermitage

de la Verna, François vit le Crucifié sous la forme d'un séraphin et de cette

rencontre avec le séraphin crucifié, il reçut les stigmates; il devint ainsi un

avec le Christ crucifié: un don qui exprime donc son intime identification avec

le Seigneur.

La mort de François – son

transitus – advint le soir du 3 octobre 1226, à la Portioncule. Après avoir

béni ses fils spirituels, il mourut, étendu sur la terre nue. Deux années plus

tard, le Pape Grégoire IX l'inscrivit dans l'album des saints. Peu de temps

après, une grande basilique fut élevée en son honneur, à Assise, destination

encore aujourd'hui de nombreux pèlerins, qui peuvent vénérer la tombe du saint

et jouir de la vision des fresques de Giotto, le peintre qui a illustré de

manière magnifique la vie de François.

Il a été dit que François

représente un alter Christus, qu'il était vraiment une icône vivante du Christ.

Il fut également appelé « le frère de Jésus ». En effet, tel était son idéal:

être comme Jésus; contempler le Christ de l'Evangile, l'aimer intensément, en imiter

les vertus. Il a en particulier voulu accorder une valeur fondamentale à la

pauvreté intérieure et extérieure, en l'enseignant également à ses fils

spirituels. La première béatitude du Discours de la Montagne – Bienheureux les

pauvres d'esprit car le royaume des cieux leur appartient (Mt 5, 3) a trouvé

une réalisation lumineuse dans la vie et dans les paroles de saint François.

Chers amis, les saints sont vraiment les meilleurs interprètes de la Bible; ils

incarnent dans leur vie la Parole de Dieu, ils la rendent plus que jamais

attirante, si bien qu'elle nous parle concrètement. Le témoignage de François,

qui a aimé la pauvreté pour suivre le Christ avec un dévouement et une liberté

totale, continue à être également pour nous une invitation à cultiver la

pauvreté intérieure afin de croître dans la confiance en Dieu, en unissant

également un style de vie sobre et un détachement des biens matériels.

Chez François, l'amour

pour le Christ s'exprima de manière particulière dans l'adoration du Très Saint

Sacrement de l'Eucharistie. Dans les Sources franciscaines, on lit des

expressions émouvantes, comme celle-ci: « Toute l'humanité a peur, l'univers

tout entier a peur et le ciel exulte, lorsque sur l'autel, dans la main du

prêtre, il y a le Christ, le Fils du Dieu vivant. O grâce merveilleuse! O fait

humblement sublime, que le Seigneur de l'univers, Dieu et Fils de Dieu,

s'humilie ainsi au point de se cacher pour notre salut, sous une modeste forme

de pain » (François d'Assise, Ecrits, Editrice Francescane, Padoue 2002, 401).

En cette année

sacerdotale, j'ai également plaisir à rappeler une recommandation adressée par

François aux prêtres: « Lorsqu'ils voudront célébrer la Messe, purs de manière

pure, qu'ils présentent avec respect le véritable sacrifice du Très Saint Corps

et Sang de notre Seigneur Jésus Christ » (François d'Assise, Ecrits, 399).

François faisait toujours preuve d'un grand respect envers les prêtres et il

recommandait de toujours les respecter, même dans le cas où ils en étaient

personnellement peu dignes. Il donnait comme motivation de ce profond respect

le fait qu'ils avaient reçu le don de consacrer l'Eucharistie. Chers frères

dans le sacerdoce, n'oublions jamais cet enseignement: la sainteté de

l'Eucharistie nous demande d'être purs, de vivre de manière cohérente avec le

Mystère que nous célébrons.

De l'amour pour le Christ

naît l'amour envers les personnes et également envers toutes les créatures de

Dieu. Voilà un autre trait caractéristique de la spiritualité de François: le

sens de la fraternité universelle et l'amour pour la création, qui lui inspira

le célèbre Cantique des créatures. C'est un message très actuel. Comme je l'ai

rappelé dans ma récente encyclique Caritas in veritate, seul un développement

qui respecte la création et qui n'endommage pas l'environnement pourra être

durable (cf. nn. 48-52), et dans le Message pour la Journée mondiale de la paix

de cette année, j'ai souligné que l'édification d'une paix solide est également

liée au respect de la création. François nous rappelle que dans la création se

déploient la sagesse et la bienveillance du Créateur. Il comprend la nature

précisément comme un langage dans lequel Dieu parle avec nous, dans lequel la

réalité devient transparente et où nous pouvons parler de Dieu et avec Dieu.

Chers amis, François a

été un grand saint et un homme joyeux. Sa simplicité, son humilité, sa foi, son

amour pour le Christ, sa bonté envers chaque homme et chaque femme l'ont rendu

heureux en toute situation. En effet, entre la sainteté et la joie existe un

rapport intime et indissoluble. Un écrivain français a dit qu'il n'existe

qu'une tristesse au monde: celle de ne pas être saints, c'est-à-dire de ne pas

être proches de Dieu. En considérant le témoignage de saint François, nous

comprenons que tel est le secret du vrai bonheur: devenir saints, proches de

Dieu!

Que la Vierge, tendrement

aimée de François, nous obtienne ce don. Nous nous confions à Elle avec les

paroles mêmes du Poverello d'Assise: « Sainte Vierge Marie, il n'existe aucune

femme semblable à toi née dans le monde, fille et servante du très haut Roi et

Père céleste, Mère de notre très Saint Seigneur Jésus Christ, épouse de l'Esprit

Saint: prie pour nous... auprès de ton bien-aimé Fils, Seigneur et Maître »

(François d'Assise, Ecrits, 163).

* * *

Je suis heureux de saluer

les pèlerins francophones présents, en particulier Mgr Perrier, évêque de

Tarbes et Lourdes qui accompagne un groupe de l'Hospitalité Notre-Dame de

Lourdes. Prions Dieu afin qu'il donne à son Eglise des saints, qui soient

eux-aussi des « autres Christ ». Bon pèlerinage à tous!

APPEL

Il y a soixante-cinq ans,

le 27 janvier 1945, étaient ouvertes les grilles du camp de concentration nazi

de la ville polonaise d'Oswiecim, connue sous le nom allemand d'Auschwitz, et

les quelques survivants furent libérés. Cet événement, ainsi que les

témoignages des survivants révélèrent au monde l'horreur de crimes d'une

cruauté inouïe, commis dans les camps d'extermination créés par l'Allemagne

nazie.

Aujourd'hui, est célébré

« la Journée de la Mémoire de l'Holocauste », en souvenir de toutes les

victimes de ces crimes, en particulier de l'extermination programmée des juifs,

et en l'honneur de tous ceux qui, au risque de leur vie, ont protégé les

personnes persécutées, s'opposant à cette folie meurtrière. Avec une âme émue,

nous pensons aux innombrables victimes d'une haine raciale et religieuse

aveugle, qui ont subi la déportation, l'emprisonnement, la mort dans ces lieux

terribles et inhumains. Que la mémoire de ces faits, en particulier du drame de

la Shoah, qui a frappé le peuple juif, suscite un respect toujours plus

convaincu de la dignité de chaque personne, afin que tous les hommes se sentent

une unique et grande famille. Que Dieu tout-puissant illumine les cœurs et les

esprits, afin que de telles tragédies ne se répètent plus !

© Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Andrea Vanni (1332–1414). Saint

François d’Assise, 1355-1360, 100 x 46, Lindenau-Museum

Saint François d'Assise

Grâce aux multiples

rameaux de 1a famille franciscaine, Saint François d'Assise est assurément le

maître spirituel qui a le plus profondément influencé la conscience religieuse

populaire en Occident, singulièrement en ce qui touche la dévotion

eucharistique. Des Opuscules qui rassemblent les écrits de Saint

François d'Assise, on peut extraire une dizaine de textes particulièrement

édifiants pour la piété eucharistique.

Deux des vingt-huit Admonitions,

que l'on s'accorde à considérer comme les premières instructions de Saint

François d'Assise à ses frères, parlent de l'Eucharistie. Dans la

première Admonition, il range parmi les damnés, la « race charnelle »

de ceux « qui ne voient pas et ne croient pas, selon l'Esprit et selon

Dieu, que ce soit là réellement les très saints Corps et Sang de Notre-Seigneur

Jésus-Christ qui, chaque jour, s’humilie, exactement comme au jour où, quittant

son palais royal, il s'est incarné dans le sein de la Vierge. » Ces gens

sont condamnés parce que la dureté de leur coeur les empêche de contempler,

c'est-à-dire de chercher à voir, « avec les yeux de l’esprit » ce

qu'ils regardent avec leurs yeux de chair : « nous aussi, lorsque de nos

yeux de chair, nous voyons le pain et le vin, sachons voir et croire fermement

que nous avons là le Corps et le Sang très saints du Seigneur vivant et vrai. »

Il est bien clair, dans la démarche spirituelle de Saint François d'Assise, que

voir au-delà de ce que l'on regarde s'acquiert par l'effort du fidèle qui se

veut accorder à l'Esprit Saint qui réside en lui, « c'est donc 1' Esprit

du Seigneur, habitant ceux qui croient en lui, qui reçoit le Corps et le Sang

très saints du Seigneur. Tous les autres, qui n'ont point part à cet Esprit et

qui osent le recevoir, mangent et boivent leur condamnation. »

Ainsi, pour le baptisé,

contempler Jésus dans l'Eucharistie et recevoir les grâces de la communion,

procède de son acceptation des dons du Saint-Esprit qui s'épanouissent dans

l'âme de celui qui s'y soumet par un effort constant de la volonté. Or, pour se

réaliser pleinement, cet effort constant de la volonté doit nécessairement,

selon Saint François d'Assise, s'accompagner de trois conditions : confession

fréquente, respect aux ministres de l'Eucharistie, vénération habituelle des

lieux de culte.

La Regula I fratrum

minorum qui remplaça la règle primitive dont le texte ne nous est pas

parvenu, souligne que les frères ne recevront la communion « que contrits

et confessés. » Saint François d'Assise signale la même exigence dans la

première lettre, adressée à tous les fidèles, et, dans la sixième lettre, il

commande à ses frères, pour toutes les prédications qu'ils font, de prêcher au peuple

la pénitence. Parce que le fidèle reçoit le Seigneur « d'un coeur pur et

dans un corps chaste », il fait des oeuvres de pénitence qui sont fruits

de salut, dont la plus grande est l'amour du prochain. Au cours du XIII°

siècle, Thomas de Celano écrivait des premiers frères mineurs : « ils

s'examinaient continuellement et repassaient dans leur esprit toutes leurs

actions, rendant grâces à Dieu pour le bien qu'ils avaient fait, gémissant et

pleurant sur leurs négligences ou leurs manques de prudence. »

Dans l'antépénultième et

vingt-sixième Admonition, Saint François d'Assise s'écrie : « bienheureux

le serviteur de Dieu qui porte foi aux clercs, et malheur à ceux qui les

méprisent ! » Et Saint François d'Assise d'ajouter, dans son

Testament : « Le Seigneur m'a donné et me donne encore, à cause de

leur caractère sacerdotal, une si grande foi en les prêtres qui vivent selon la

règle de la sainte Eglise romaine, que même s'ils me persécutaient, c'est à eux

que je veux avoir recours ... Je veux les craindre, les aimer et les honorer

comme mes seigneurs. » Les prêtres ne sont pas vénérables à cause

d'eux-mêmes, écrivait Saint François d'Assise dans la première lettre, car ils

peuvent être pécheurs, mais à cause de leur charge de « ministres du Corps

et du Sang très saints de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ qu'ils sacrifient sur

l'autel, qu'ils reçoivent eux-mêmes et dont ils sont les dispensateurs pour les

autres. »

Saint François d'Assise,

dans sa première lettre, conjugue les nécessités de « visiter fréquemment

les église et de révérer les prêtres. » Dans sa deuxième lettre il déplore

les profanateurs qui « laissent l'Eucharistie à l'abandon, en des endroits

malpropres, la portant sans honneur dans les rues, la recevant indignement et

la distribuant aux autres sans discernement. » Il exige que la Présence

Réelle soit entourée d'honneur et de vénération, il entend qu'on observe les

règles du culte, qu'on place les saintes espèces « dans des lieux

précieusement ornés » , qu' on soit attentif à l'état des vases sacrés et

des linges, autant d'actes formels et d'attitudes révérencielles qui portent à

la contemplation. « Je vous en prie donc instamment, vous tous, mes

frères, en vous baisant les pieds et avec tout l'amour dont je suis

capable : témoignez toute révérence et tout honneur, aussi grandement que

vous pourrez, au Corps et au Sang très saints de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ,

en tout ce qu'il y a dans le ciel et tout ce qu'il y a sur la terre a été

pacifié et réconcilié au Dieu tout-puissant. »

Fondée sur une expérience

mystique privilégiée, la spiritualité de Saint François d'Assise mène à

l'adhérence totale au Christ à travers son imitation nourrie dans la méditation

de tous les aspects du Christ, singulièrement, comme nous le chantons à Noël,

de la crèche au crucifiement. Or, le Christ que Saint François d'Assise voulait

imiter exactement, et qui sanctionna cette adéquation par le don des stigmates,

se révélait à lui, immédiatement et sensiblement, dans l'Eucharistie. Son âme,

éprise de sa propre purification, ordonnée au Seigneur par ses mortifications,

communiait activement.

Se mettre à l'école du

père séraphique, exige que l'on s'échine à considérer le Christ sous tous ses

aspects pour pouvoir discerner, dans nos propres vies, ceux auxquels il nous

associe et que nous reproduisons dans le siècle. Comme le résumeront plus tard

les pères de l'École française de spiritualité, mettre Jésus devant nos yeux,

pour qu'il pénètre nos coeurs, puis anime nos mains. Pour parler comme Bossuet

à propos de l'Église, le chrétien n'est autre que le Christ répandu et

communiqué. Cependant le fidèle ne saurait être au Christ en dehors de l'Eglise

qui, d'une part, transmet son enseignement et, d'autre part, communique sa vie.

Enfin, à l'exemple et par l'intercession de la Vierge Marie, le chrétien se

laisse saisir par le Saint-Esprit pour engendrer spirituellement les âmes dans

le Christ et l'Église, opération qui s'accomplit chez celui qui accueille dans

sa propre vie le Christ sous tous ses aspects, qui vise à aimer Dieu et le

prochain par des oeuvres pieuses et miséricordieuses, qui cherche toujours

davantage la pureté du coeur par l'examen de sa conscience et la réforme de

soi.

Voilà donc ce que chacun

de nous doit attendre de la communion qui sera d'autant plus efficace que,

avant de la recevoir, il se sera déjà préparé à ses fruits par d'actifs

exercices de soumission aux dons du Saint-Esprit. Au lieu d'attendre béatement

que l'Eucharistie, reçue plus ou moins dignement, veuille bien nous transformer

à l'image du Christ, ayons soin de nous préparer à cette conversion par l'obéissance

à l'enseignement de l'Église, par la vénération du Saint-Sacrement, par des

actes de charité fraternelle, par la contrition, la pénitence et la confession.

Que le ministère de la Vierge Marie, Mère de Dieu et notre Mère, nous y aide

par l’intermédiaire des saint anges et l’intercession des saints.

O Frères bien aimés, ô

Fils béni pour l'éternité, écoutez-moi, écoutez la voix de votre Père :

nous avons promis de grandes choses ; de plus grandes nous sont

promises : observons les unes, soupirons après les autres.

Le plaisir est court, la

peine est éternelle. La souffrance est passagère, la gloire est infinie.

Beaucoup sont appelés, peu sont élus. Tous sont rétribués. Mes Frères, pendant

que nous en avons le temps, faisons le bien.

Saint François d'Assise

Des profondeurs de

l'éternité, Dieu appelle chacun de nous à l'existence : Dès avant la

fondation du monde, écrivait saint Paul aux Ephésiens, il nous a élu

en lui ; en nous créant, le Seigneur a déjà pour chacun de nous des

projets et, tout au long de notre vie, il nous appelle constamment à les

réaliser par des dépassements de nous-mêmes qui nous font de plus en plus

devenir, avec le secours de sa grâce, ce qu'il attend de nous depuis toujours.

Dieu ne crée pas au

hasard des êtres à qui, selon la nécessité, il donnerait une vocation, mais il

peut dire à chacun, comme au prophète Jérémie : avant de te former au

ventre de ta mère, je t'ai connu, avant même que tu sois sorti du sein, je t'ai

consacré.

Peut-être avez-vous eu de

grands rêves ... Sans doute avez-vous planifié votre avenir... Ou, plus

simplement, dans une attente diffuse, vous ne savez pas où la vie vous mènera

... Quoi qu'il en soit du dessein de Dieu sur vous, il vous faut le découvrir

de sorte qu'on ne puisse pas vous reprocher d'avoir gaspillé vos talents.

Invoquez l'aide et

l'intercession de saint François d'Assise, mettez-vous à son école pour savoir

répondre à votre vocation comme il le fit lui-même dans la petite église de

Saint Damien.

Ne placez jamais votre

confiance dans les moyens de la puissance humaine, mais ceux dans la grâce

divine : appliquez votre intelligence aux vérités que le Seigneur nous a

révélées, observez les commandements qu'ils nous donnés, recevez les secours

qu'il nous a préparés.

Puisez dans la prière et

la mortification vos énergies pour concrétiser votre communion au Christ

crucifié qui vous appelle à vous offrir avec lui pour le salut des hommes.

Efforcez-vous de lire

l'Évangile, de le méditer et essayez de l'appliquer à la lettre et sans

glose. Vous pourrez dire alors avec saint François : Personne ne me

montra ce que je devais faire, mais le Très-Haut lui-même me révéla que je

devais vivre selon le saint Évangile.

Quoi qu'il arrive, restez

fidèles à l'Eglise ; uni au Pape et à tous les fidèles, priez et oeuvrez dans

l'Eglise militante ; imitez ce que vous pouvez de vie des saints, appelez leur

aide et confiez-vous à l'intercession de l'Eglise triomphante ; intercédez pour

la libération des âmes de l'Eglise souffrante.

Travaillez de vos mains à

la construction de l'Eglise, cherchez à acquérir les compétences qui vous

manquent, sachez faire profiter les autres de vos richesses spirituelles,

intellectuelles et matérielles.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/04.php

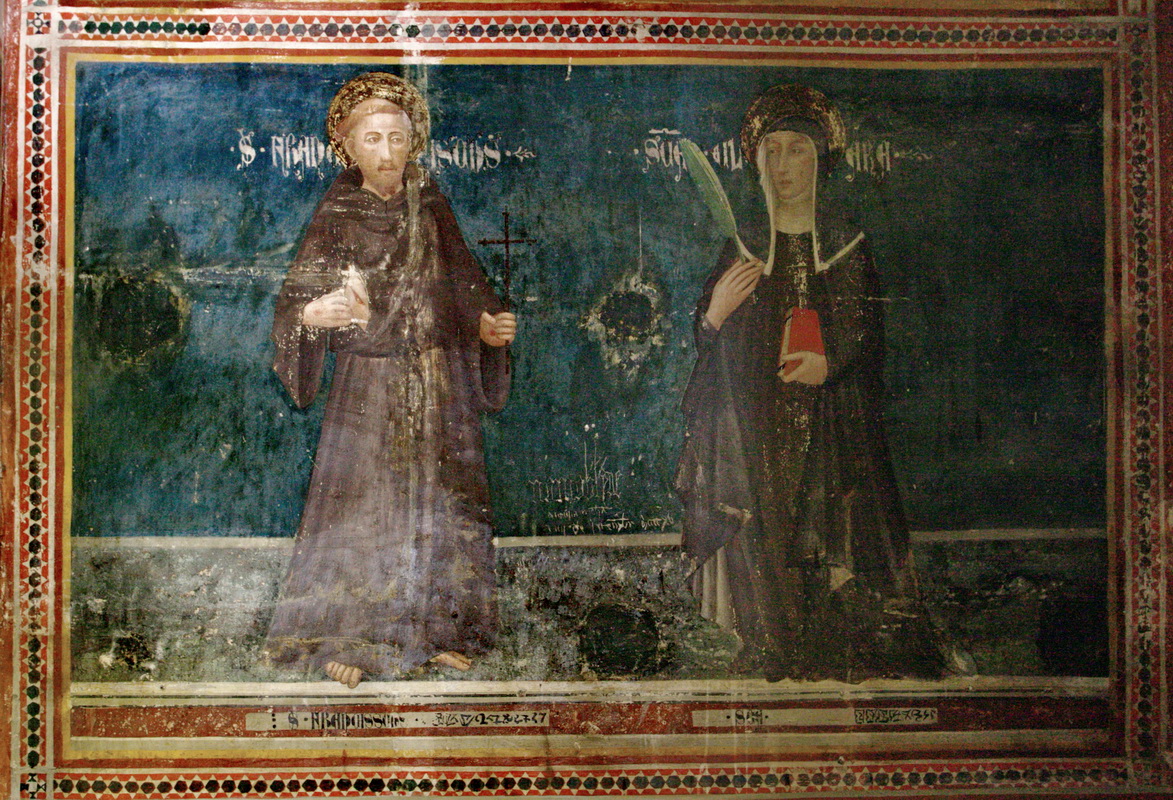

Ferrer Bassa (1285/1290 – 1348). Sant

Francesc i Santa Clara, circa 1346, fresco, Monastery of Pedralbes

La vraie sagesse

Nous ne devons pas être

sages et prudents selon la chair, mais bien plutôt simples, humbles et purs.

Nous ne devons jamais

désirer dominer les autres, mais bien plutôt nous devons être les serviteurs et

les sujets de toute créature humaine pour l’amour de Dieu. Et sur tous ceux qui

auront agi ainsi et persévéré jusqu’à la fin « l’Esprit du Seigneur se reposera,

et il fera en eux son habitation et sa demeure » (cf. Jn 14, 17), et

ils seront les fils du Père céleste (Mt 5, 45) dont ils

accomplissent les œuvres ; ils sont les époux, les frères et les mères de

notre Seigneur Jésus Christ. Nous sommes ses époux quand par l’Esprit Saint

l’âme fidèle est unie à Jésus Christ ; nous sommes ses frères

quand nous faisons la volonté de son Père qui est dans les cieux (Mt

7, 21) ; nous sommes ses mères quand nous le portons dans notre cœur et

dans notre corps, par l’amour et par une conscience pure et sincère, et quand

nous l’enfantons par nos œuvres saintes, dont l’exemple doit éclairer le

prochain.

St François d’Assise

Saint François d’Assise

(† 1226), fondateur de l’ordre des Franciscains, fut, avec saint Dominique, l’un

des artisans majeurs d’un renouveau spirituel de l’Église romaine. / « Lettre à

tous les fidèles », Œuvres, Paris, Albin Michel, coll. « Spiritualités

vivantes », 2006, p. 140-141.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/lundi-9-aout/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Giotto

di Bondone (1267-1337), Le songe d’Innocent III (Vie de saint François),

circa 1295, Assise,

Basilique supérieure

SAINT FRANÇOIS D’ASSISE

Né en 1182, mort en 1226.

Canonisé en 1228, fête immédiate.

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon. François

naquit à Assise en Ombrie, et suivit l’exemple de son père, en se livrant au

commerce, dès sa jeunesse. Un jour qu’un pauvre lui demanda l’aumône pour

l’amour de Jésus-Christ, François, contre son habitude, le repoussa d’abord,

mais troublé aussitôt de ce refus, il lui accorda plus qu’il n’avait coutume de

donner, et, le jour même promit à Dieu de ne jamais refuser son aumône à

quiconque la lui demanderait. Quelque temps après il tomba gravement malade, et

à peine fut-il guéri qu’il commença à se livrer très ardemment aux offices de la

charité, et fit de tels progrès dans cette vertu qu’épris de la perfection

évangélique il distribuait aux pauvres tout ce qu’il possédait. Son père ne put

souffrir une telle conduite, aussi l’obligea-t-il, par devant l’Évêque

d’Assise, à renoncer à tous les biens patrimoniaux. François abandonna tout et

jusqu’à ses habits, disant que désormais il aurait un motif de plus de répéter

: Notre Père, qui êtes aux cieux.

Cinquième leçon. Ayant

entendu lire cette parole de l’Évangile : « Ne possédez ni or, ni argent, ni

aucune monnaie dans vos ceintures, ni sac pour la route, ni deux tuniques, ni

chaussures, » François se proposa de la prendre pour règle de vie. Quittant

donc ses chaussures, se contentant d’une seule tunique, et s’associant douze

compagnons, il institua l’Ordre des Mineurs. En l’année mil deux cent neuf, il

se rendit à Rome, pour que le Saint-Siège confirmât la règle de son Ordre. Sa

demande fut d’abord rejetée par le souverain Pontife Innocent III. Mais ayant

vu en songe, pendant la nuit, celui qu’il avait repoussé, soutenir sur ses

épaules la basilique de Latran chancelante, le Pape, troublé par cette vision,

fit rechercher François, le reçut avec bonté et confirma sa règle. Le saint

fondateur envoya donc ses frères prêcher l’Évangile dans tout l’univers ; et

lui-même, ambitionnant la gloire du martyre, fit voile pour la Syrie, où il fut

reçu par le Soudan avec toutes sortes d’égards. N’obtenant pas le résultat

qu’il désirait, il revint en Italie.

Sixième leçon. Après avoir construit quantité de maisons de son institut, François se retira dans la solitude, sur le mont Alverne. Ayant commencé là un jeûne de quarante jours, en l’honneur de l’Archange saint Michel, il advint qu’en la fête de l’Exaltation de la sainte Croix, un Séraphin lui apparut, portant entre ses ailes l’image du Crucifié. Ce Séraphin imprima sur les mains, les pieds et le côté de François, les stigmates des clous. Saint Bonaventure affirme dans ses lettres avoir entendu le Pape Alexandre IV déclarer, dans un sermon, qu’il avait vu les stigmates. Ces témoignages de l’amour de Jésus-Christ excitèrent l’admiration de tous. Enfin, deux ans après, se sentant gravement malade, François voulut qu’on le transportât dans l’église de Sainte-Marie-des-Anges, afin de rendre, son dernier souffle là même où Dieu lui avait accordé la vie de la grâce. En ce lieu, il exhorta ses frères à conserver très fidèlement la pauvreté, la patience et la foi de la sainte Église romaine. Pendant qu’il récitait le Psaume : « De ma voix, j’ai crié vers le Seigneur, » étant arrivé à ce verset : « Des justes m’attendent jusqu’à ce que vous m’exauciez, » il rendit son âme à Dieu. C’était le quatrième jour des nones d’octobre. De nombreux miracles l’ayant illustré, Grégoire IX l’inscrivit au catalogue des Saints.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/04-10-St-Francois-d-Assise

Giovanni Bellini (circa 1430–1516),

Francis of Assisi in the Desert, circa 1480,

oil and tempera on poplar wood, 124,4 x 141,9, The Frick Collection

Prière de Saint-François

d'Assise

"Seigneur, fais de

moi un instrument de ta paix,

Là où est la haine, que

je mette l'amour.

Là où est l'offense, que

je mette le pardon.

Là où est la discorde,

que je mette l'union.

Là où est l'erreur, que

je mette la vérité.

Là où est le doute, que

je mette la foi.

Là où est le désespoir,

que je mette l'espérance.

Là où sont les ténèbres,

que je mette la lumière.

Là où est la tristesse,

que je mette la joie.

O Seigneur, que je ne

cherche pas tant à

être consolé qu'à

consoler,

à être compris qu'à

comprendre,

à être aimé qu'à aimer.

Car c'est en se donnant

qu'on reçoit,

c'est en s'oubliant qu'on

se retrouve,

c'est en pardonnant qu'on

est pardonné,

c'est en mourant qu'on

ressuscite à l'éternelle vie."

Giotto,

François d'Assise prêchant aux oiseaux (d'après les Fioretti), Basilique Assise

SAINT FRANÇOIS *

François s'appela,

d'abord Jean, mais, dans la suite; il changea de nom et s'appela François. Il

paraît que ce fut pour plusieurs motifs que ce changement ut lieu. 1° Comme

souvenir d'une chose merveilleuse; savoir: qu'il reçut de Dieu d'une manière

miraculeuse le don de la langue française ; ce qui fait dire dans sa légende

que, toujours, quand il était embrasé du feu de l’Esprit Saint, il exprimait en

français ses émotions brûlantes. 2° Afin que son ministère fût manifesté; c'est

pour cela qu'il est dit dans sa légende que ce fut par un effet de la sagesse

divine qu'il, fut ainsi appelé, afin due par ce nom singulier, que personne

n'avait encore porté, le but de son ministère fût plus vite connu dans tout

l’univers. 3° Pour indiquer les résultats qu'il devait obtenir; car, ainsi, on

donnait à comprendre que, par lui et par ses enfants, il devait rendre francs

et libres une quantité d'esclaves du péché et du démon. 4° A raison de sa

magnanimité de cœur, car franc vient de férocité; il y a, en effet., dans le

caractère français; un instinct de férocité joint à la magnanimité. 5° En

raison de la vertu de sa parole, qui tranchait dans le vice comme une

francisque. 6° Pour la terreur que le démon ressentait quand François le

mettait en fuite. 7° Pour sa sécurité dans la vertu, la perfection de ses

oeuvres et l’honnêteté de sa manière de vivre. On dit, en effet, que les

francisques étaient des insignes ayant la forme de haches, portées au-devant

des consuls, comme marque .de terreur, de sécurité et d'honneur tout à la fois.

François, le serviteur et

l’ami du Très-Haut, né dans la ville d'Assise, et négociant, vécut dans la

vanité jusqu'à l’âge de près de vingt ans. Notre-Seigneur se servit du fouet de

l’infirmité pour le corriger et le changea subitement en un autre homme, en

sorte que, dès cet instant, l’esprit de prophétie commença à se faire remarquer

en lui. Une fois, en effet, que pris avec beaucoup d'autres par des Pérousins,

il avait été mis en une dure prison, quand tous ses compagnons étaient dans la

tristesse, seul il entra dans des transports de joie ; et comme ils l’en

reprenaient, il leur dit : « Vous saurez que si je me réjouis, c'est que je.

serai honoré, comme un saint, du monde entier. » Un jour, dans un voyage qu'il

faisait à Rome par dévotion, il se dépouilla de ses habits et prenant ceux d'un

pauvre, il s'assit au milieu des mendiants devant l’église de Saint-Pierre; il

mangea avidement avec eux, comme l’un d'entre eux; ce qu'il eût fait plus

souvent s'il n'eût été retenu par respect pour lés personnes de sa

connaissance. L'antique ennemi s'efforçait de le détourner de son bon propos,

et lui rappela le souvenir d'une femme de son pays monstrueusement bossue, en

le menaçant de le rendre comme elle, s'il ne se désistait de son entreprise ;

mais le Seigneur qui le fortifia lui fit entendre ces paroles : «

François, les choses amères, prends-les pour douces, et méprise-toi toi-même,

si tu désires me connaître. » Il rencontra lors un lépreux, et quoique

tous ceux qui sont affligés de cette maladie soient un sujet d'horreur, il se

rappela l’oracle divin et courut embrasser ce lépreux, qui disparut aussitôt

après. A l’instant il se hâte d'aller dans les asiles des lépreux, leur

embrasse les mains avec dévotion et leur donne de l’argent. II entre pour faire

sa prière dans l’église de Saint-Damien, et une image du Christ lui

adresse miraculeusement ces paroles : « François, va réparer ma maison, qui,

comme tu le vois, s'écroule de toutes parts. » A dater de ce moment, son âme

s'était comme fondue et la compassion pour J.-C. crucifié fut merveilleusement

empreinte en son cœur. Il mit tous ses soins à réparer l’église, et après avoir

vendu ce qu'il avait, il voulait en donner l’argent à un prêtre; comme celui-ci

refusait de le recevoir par crainte des parents de François, le saint jeta cet

argent, en sa présence, comme une poussière méprisable. Ce fut alors que son

père le fit saisir et lier, mais François lui rendit le prix de la vente de ses

biens, et se défit pareillement de son habit; dans cet état de nudité il se

jeta dans les bras du Seigneur, et se revêtit d'un cilice. Le serviteur de Dieu

appelle alors un simple particulier qu'il regarde comme son père en sollicitant

ses bénédictions à la place de celui qui l’accablait de malédictions. Son frère

le rencontra, un jour d'hiver, couvert de haillons, et en prières. En le voyant

tout grelottant, il dit à quelqu'un : « Demande à François de te vendre une

once de sueur. » Ce qu'entendant François, il répondit : « Vraiment j'en

vendrai à mon Seigneur (Chronique de l’Ordre de Saint-François, Ire p. l. I, c.

v).» Un jour qu'il avait entendu ces paroles adressées par Notre-Seigneur à ses

disciples, quand il les envoya prêcher, à l’instant il se mit en devoir de les

pratiquer toutes à la lettre : il ôte ses souliers, se couvre d'une seule

tunique, encore est-elle grossière et à la place d'une ceinture de cuir, il

emprunte une corde. Par un temps de neige, et passant dans une forêt, il fut

pris par des larrons; ils lui demandèrent qui il était, il répondit qu'il est

le héraut de Dieu. Alors ils le prirent et le jetèrent dans la neige, en

disant: « Dors, rustique héraut de Dieu. »

Beaucoup de nobles et de

roturiers, tant clercs que laïques, quittèrent les pompes du monde pour

s'attacher à lui. Ce père en sainteté leur enseigna à pratiquer la perfection

évangélique, à embrasser la pauvreté et à marcher dans: la voie de la sainte

simplicité. Il écrivit en outre une règle évangélique pour lui et

les frères qu'il avait et qu'il aurait, règle qui fut confirmée par le pape

Innocent III. Depuis lors, il commença à répandre avec plus de ferveur que

jamais la semence de la parole de Dieu, et à parcourir les villes et les

bourgs, animé d'un zèle admirable. — Il y avait un frère qui, extérieurement,

paraissait d'une éminente sainteté, toutefois il était fort original; il

observait la règle du 'silence avec une telle rigueur qu'il ne se confessait

que par signes et non de vive voix. Tout le monde le louait comme un saint,

mais l’homme de Dieu vint dire : « Cessez, mes frères, de louer en lui des

illusions diaboliques : Qu'on l’avertisse de se confesser une fois ou d'eux par

semaine; que s'il ne le fait pas, il y a tentation du diable et supercherie. »

Quand les frères donnèrent cet. avis à cet homme, il mit un doigt sur sa bouche

et secouant la tête, il fit signe qu'il ne se confesserait pas. Peu de jours

après; il retourna à son vomissement et mourut après avoir passé sa vie dans

des actions criminelles. — Dans un voyage, le serviteur de Dieu fatigué allait

monté sur un âne; son compagnon frère Léonard d'Assises, qui . était aussi

fatigué, se mit à penser et à dire en lui-même : « Ses parents et les miens ne

jouaient pas de pair ensemble. » A l’instant l’homme de Dieu descendit de son

âne et dit à son frère : « Il n'est pas convenable que j'aille sur un âne et

que vous alliez à pied, car vous avez été plus noble que moi. » Le frère,

stupéfait, se jeta aux pieds du père et lui demanda pardon. — Il rencontra, un

jour sur son passage, une femme noble qui marchait à pas précipités. Le saint eut

pitié de sa fatigue et de l’état d'oppression qui en était la suite; il lui

demanda ce qu'elle cherchait « Priez pour moi, mon père, lui dit-elle, parce

que mon mari m’empêche de mettre à exécution un salutaire propos que j'ai

résolu de suivre; et il me gêne fort de servir J.-C. » Saint François lui dit :

« Allez, ma fille, dans peu, vous en recevrez de la consolation, et vous lui

annoncerez, de la part de Dieu tout-puissant et de la mienne, que c'est

maintenant pour lui le temps du salut, plus tard, ce sera celui de la justice.

» Cette femme rapporta ces paroles à son mari qui se trouva changé tout d'un

coup et promit de garder la continence. — Un paysan mourait de soif dans un

lieu désert; le saint lui obtint au même endroit une fontaine par ses prières.

— Par l’inspiration du Saint-Esprit, il révéla le secret suivant à un des

frères qui était de ses intimes : « Il existe aujourd'hui sur la terre un

serviteur de Dieu, en faveur duquel, tant qu'il sera en vie, le Seigneur ne

permettra pas que la famine sévisse sur les hommes. » Or, on raconte que la

prédiction se réalisa effectivement : mais quand il fut mort, il en arriva tout

autrement; car, après son heureux trépas, il apparut au même frère et lui dit :

« Voici la famine, que,

tout le temps de ma vie, le Seigneur ne laissa pas venir sur la terre.» — A la

fête de Pâques, les frères grecs du désert avaient préparé la table d'une

manière plus recherchée qu'à l’ordinaire, avec des nappes et des verres ; quand

l’homme de Dieu eut vu cela, il se retira à l’instant; il se mit sur la tête le

chapeau d'un pauvre qui se trouvait là pour lors, et un bâton à la main, il

sort dehors et va attendre à la porte. Pendant que les frères étaient à table,

il criait à la porte que, pour l’amour de Dieu, ils donnassent l’aumône à un

pèlerin pauvre et infirme. On appelle le pauvre, on le fait entrer : il

s'assied par terre à l’écart et pose son plat sur la cendre. Les frères, voyant

cela, furent tout stupéfaits, et il leur dit «J'ai vu la table parée et ornée,

je me suis aperçu que ce n'est pas là l’ordinaire de pauvres qui vont mendier

de porte en porte. »

Il aimait à tel point la

pauvreté en lui et chez les autres qu'il appelait toujours la pauvreté sa dame

mais quand il voyait quelqu'un plus pauvre que lui, il en était jaloux et

craignait d'être dépassé en cela par autrui. En effet; un jour qu'il avait

rencontré une pauvre femme, il dit à son compagnon : « Le dénument de

cette personne nous a fait honte; c'est une critique achevée de notre pauvreté,

car à la place de mes richesses, j'ai fait choix de la pauvreté pour ma dame et

voici qu'elle reluit plus en cette femme qu'en moi (Hist. ord. Min., Ire p., I.

VI, c. CVII). » — Un pauvre vint à passer devant lui, et l’homme de Dieu

en fut touché d'une vive compassion; alors son compagnon lui dit : « Bien que

cet homme soit pauvre, peut-être aussi n'y en a-t-il pas dans tout le pays qui

soit plus riche en désir. » L'homme de Dieu répliqua: « Dépouillez-vous vite de

votre tunique, donnez-la à ce pauvre, jetez-vous à ses pieds et reconnaissez

hautement la faute dont vous venez de vous rendre coupable. » Le compagnon

obéit tout aussitôt. — Une fois il rencontra trois femmes semblables en tout

pour la figure et pour la manière d'être, et elles le saluèrent en ces termes :

« Que dame pauvreté soit la bienvenue », et elles disparurent de suite, sans

qu'on les ait plus jamais vues. — En venant à Arezzo où une guerre intestine

s'était émue, l’homme de Dieu vit du faubourg des démons qui se réjouissaient

au-dessus de ce pays; et appelant son compagnon nommé Silvestre, il lui dit : «

Allez à la porte de la ville, et, de la part de Dieu tout-puissant, commandez

aux démons d'en sortir. » Silvestre se hâta d'aller à la porte, où il cria avec

force : « De la part de Dieu et par l’ordre de notre père François, démons,

sortez, tous. » Peu de temps après, la concorde se rétablit parmi les citoyens.

— Ce même Silvestre, n'étant encore que prêtre séculier, vit en songe sortir de

la bouche de saint François une croix d'or dont le sommet touchait le ciel, et

les bras étendus au large embrassaient l’une et l’autre partie du monde. Touché

de componction, le prêtre quitta aussitôt le monde et devint un parfait

imitateur de l’homme de Dieu.

L'homme de Dieu était en

oraison et le diable l’appela trois fois par son nom. Le saint lui répondit, et

le diable ajouta : « Il n'est dans ce monde aucun homme, tel pécheur qu'il

soit, auquel le Seigneur ne fasse miséricorde, s'il se convertit ; mais celui

qui se tuera par une dure pénitence, ne trouvera jamais miséricorde. » Aussitôt

le serviteur de Dieu connut par révélation la malice de l’ennemi qui s'était

efforcé de le faire tomber dans la tiédeur. Mais l’antique ennemi voyant qu'il

n'avait pas eu le dessus de cette manière, lui inspira une forte tentation de

la chair ; en la ressentant, l’homme de Dieu se dépouilla de son habit et se

frappa avec une corde très mince, très serrée, en disant Allons, frère l’âne,

garde-toi bien de remuer, voilà comment il faut subir le fouet. » Mais comme la

tentation tardait à s'éloigner, saint François alla se précipiter tout nu dans

une neige épaisse, puis prenant de cette neige, il en fit sept blocs cri forme

de boule, et se les mettant sous les yeux, il parla à son corps « Vois, lui

dit-il : celle-ci qui est plus grosse, c'est ta femme ; de ces quatre, deux

sont tes fils et deux sont tes filles, les deux qui restent sont ton domestique

et ta servante. » Hâte-toi de les revêtir toutes, car elles meurent de froid;

mais si ces soins multipliés t'importunent, ne sers que le Seigneur avec

sollicitude. » Aussitôt le diable confus se retira et le saint revint à sa

cellule en glorifiant Dieu. — Il logeait depuis quelque temps chez Léon,

cardinal de Sainte-Croix, qui l’avait invité. Une nuit les démons vinrent le

battre avec la plus grande violence. Il appela alors son compagnon et lui dit :

« Les démons sont des hommes d'affaires destinés par Notre-Seigneur pour punir

nos excès : or, je ne me rappelle pas avoir commis une faute que je n'aie

expiée avec la miséricorde de Dieu et par la satisfaction; mais peut-être que

le majordome (Castaldus.

Sic appellabant Longobardi locorum, praediorum ac villarum praefectos, rerum dominicarum actores, procuratores, administratores, villicos. Ducange,V° Castaldus)

a permis que ses gens se ruent sur moi, parce que je demeure à la cour des

grands; ce qui a pu fournir à mes pauvres petits frères l’occasion de concevoir

de mauvais soupçons, quand ils me voient vivre dans les délices et,

l’abondance. » Il se leva de grand matin et s'en alla. — Il était en oraison,

un jour qu'il entendit sur le toit de la maison, des troupes de démons qui

couraient avec grand bruit : aussitôt il sortit et faisant sur lui le signe de

la croix, il dit : « De la part du Dieu tout-puissant, je vous dis, démons, de

faire sur mon corps tout ce qui vous est permis : je suis disposé à tout

supporter, parce que n'ayant pas de plus grand ennemi que mon corps, vous me

vengerez de mon adversaire, pendant qu'à ma place, vous exercerez vengeance

contre lui. » Alors les démons confus s'évanouirent. — Un frère, le compagnon

de l’homme de Dieu, vit, en extase, parmi les trônes du ciel, un de ces trônes

très remarquable et brillant d'une gloire extraordinaire. Plein d'admiration il

se demandait à qui ce siège éclatant était réservé, et il entendit qu'on lui

disait : « Ce siège a appartenu à un des princes chassés du ciel et maintenant

il est préparé à l’humble François. » Après sa prière, il demanda à l’homme de

Dieu : « Que pensez-vous de vous-même, père? » « Je me considère, répondit

le saint, comme un très grand pécheur. » Et aussitôt l’Esprit dit dans le coeur

du frère « Sache que ce que tu as vu est véritable; parce que l’humilité

élèvera le plus humble de tous au trône qui a été perdu par l’orgueil. »

Dans une vision, le

serviteur de Dieu aperçut au-dessus de lui un séraphin crucifié qui imprima les

marques de sa crucifixion d'une manière si évidente sur François que le saint

paraissait avoir été lui-même crucifié. Ses mains, ses pieds et son côté,

furent marqués du caractère de la croix; mais il cacha ces stigmates à tous les

yeux avec grand soin. Quelques-uns cependant les virent de son vivant; mais à

sa mort, il y en eut beaucoup qui les considérèrent. L'existence réelle de ces

stigmates fut confirmée par de nombreux miracles, dont il suffira d'en

rapporter deux qui eurent lieu après son décès. Dans la Pouille, un homme

appelé Roger, qui avait sous les yeux l’image de saint François, se mit à

penser ceci en lui-même: « Serait-il vrai qu'il eût été honoré d'un pareil

miracle; ou bien serait-ce une pieuse illusion, ou même une fourberie inventée

par ses frères ? » Tandis qu'il roulait cela dans son esprit, tout à coup il

entendit, un bruit semblable à celui d'un javelot lancé, par une baliste, et se

sentit grièvement blessé à la main gauche; mais comme il n'y avait aucune

déchirure à son gant, il l’ôta et trouva sur la paume de sa main une blessure

profonde faite comme par une flèche. Il en résultait une chaleur si vive qu'il

semblait devoir entièrement défaillir de douleur et de chaleur. Alors il se repentit

et témoigna croire à la réalité des stigmates de saint François ; deux jours

après, ayant prié le saint par ses stigmates, il fut aussitôt guéri. — Au

royaume de Castille, un homme dévot, à saint François allait à complies, et fut

la victime innocente d'embûches dressées pour faire mourir un autre que lui ;

il fut mortellement blessé et laissé pour mort. Après quoi, sort cruel

meurtrier lui enfonça une épée dans la gorge et ne pouvant la retirer, il

s'enfuit. On accourt, de toutes parts, on s'écrie et on le pleure comme un

homme mort. Or, à minuit, comme la cloche des frères sonnait les matines, sa

femme se mit à lui crier: « Mon maître, lève-toi et va aux matines ; voici la

cloche qui t'appelle. » Aussitôt le blessé lève la main et semble faire signe à

quelqu'un d'extraire l’épée, quand, aux yeux de tous, voici l’épée qui saute en

l’air comme si elle eût été lancée par un poignet très vigoureux : à l’instant

cet homme se leva parfaitement guéri en disant: « Le bienheureux François est

venu à moi, et apposant ses stigmates sur mes blessures, il en a rempli chacune

d'elles d'une onction suave et les a guéries miraculeusement par ce contact:

comme il voulait se retirer, je lui faisais signe d'ôter l’épée, parce que je

ne pouvais parler autrement. Il la saisit et la jeta avec force et aussitôt il

guérit entièrement ma gorge, en passant doucement ses stigmates dessus. » —

Saint François et saint Dominique, ces deux lumières du monde, se trouvaient à

Rome en compagnie du cardinal d'Ostie qui fut dans la suite souverain pontife.

Cet évêque leur dit : « Pourquoi ne faisons-nous pas de vos frères des évêques

et des prélats qui l’emporteraient sur les autres par leur enseignement et

leurs exemples ? » Ce fut à qui répondrait le premier. L'humilité de saint François

lui donna la victoire en ne s'avançant pas : saint Dominique remporta aussi la

victoire en répondant le premier par obéissance. Saint Dominique répondit donc

: « Seigneur, s'ils veulent le reconnaître, mes frères ont été élevés à une

position convenable; et tant que cela sera en mon pouvoir, je ne souffrirai pas

qu'ils obtiennent d'autre marque de dignité. » Après quoi saint François prit

la parole et répondit : « Seigneur, mes frères ont été appelés mineurs, afin

qu'ils n'eussent pas la présomption de devenir majeurs. » Saint François, qui

avait la simplicité d'une colombe, invitait toutes les créatures à l’amour du

Créateur; il prêchait les oiseaux qui l’écoutaient, qui se laissaient toucher

par lui et qui ne se retiraient qu'après en avoir reçu la permission. Des

hirondelles babillaient tandis qu'il prêchait, elles se turent immédiatement

après qu'il leur eut donné ordre de le faire.

A la Portioncule,

une cigale qui restait sur un figuier, vis-à-vis de sa cellule, chantait

souvent. L'homme de Dieu étendit la main et l’appela en disant : « Ma soeur la

cigale, viens à moi. » L'insecte obéissant monta aussitôt sur la main de saint

François qui lui dit :

« Chante, ma soeur la

cigale, et loue ton. Seigneur. Elle se mit aussitôt à chanter et ne se retira

qu'après avoir été congédiée. Il ne touchait ni aux lanternes, ni aux lampes,

ni aux chandelles, car il ne voulait pas en ternir l’éclat avec sa main. Il marchait

sur les pierres avec révérence par considération, pour celui qui s'appelle

Pierre. Il ôtait les vers de dessus le chemin de crainte qu'ils ne fussent

écrasés sous les pieds des passants. Afin que les abeilles ne mourussent pas au

milieu du froid de l’hiver, il leur faisait donner du miel et ce qu'il y a de

meilleur en vin. Tous les animaux il les appelait ses frères. Rempli d'une joie

merveilleuse et ineffable dans son amour pour le Créateur, il contemplait le

soleil, la lune et les étoiles et les invitait à aimer le Créateur. Il

empêchait qu'on ne lui fît une grande couronne en disant: « Je veux

que mes frères simples aient part en mon chef. » — Un homme fort mondain, ayant

rencontré le serviteur de Dieu François qui prêchait à Saint-Séverin, vit,

par une révélation divine, deux épées très brillantes placées en travers sur le

saint en forme de croix; l’une allait de la tête aux pieds et la seconde

s'étendait d'une main à l’autre en passant transversalement par sa poitrine.

Or, il n'avait jamais vu François, mais il le reconnut à cette marque: alors il

fut touché, entra dans l’ordre des frères Mineurs où il mourut heureusement. —

Les larmes qu'il versait constamment. lui firent contracter une maladie aux

yeux; on lui conseilla alors de cesser de pleurer; mais il répondit : « Ce

n'est pas par amour pour cette lumière qui nous est commune avec les mouches

qu'il faut renoncer à voir la lumière éternelle. » — Ses frères le pressaient

de se laisser faire une opération à cause de son mal d'yeux, et le chirurgien

avait en main un instrument de fer rougi au feu; alors l’homme de Dieu dit : «

Mon frère, le feu, sois doux et courtois pour moi. Je prie le Seigneur qui t'a

créé de tempérer pour moi ta chaleur. » Et en disant cela il fit le signe de la

croix sur l’instrument qui fut enfoncé dans la chair vive depuis l’oreille

jusqu'au sourcil, sans qu'il en ressentît aucune douleur; il le témoigna

lui-même. — Le serviteur de Dieu était attaque d'une très grave maladie à

l’ermitage de Saint-Urbain. Sentant lui-même que la nature était en

défaillance, il demanda à boire du vin, mais il n'y en avait point: on lui

apporta de l’eau qu'il bénit en faisant le signe de la croix ; et à l’instant

elle fut changée en un vin excellent. La pureté du saint homme lui fit obtenir

ce que la pauvreté d'un lieu désert n'avait pu lui procurer : il n'en eut pas

plutôt goûté qu'il entra de suite en convalescence. Il préférait les mépris aux

louanges : et lorsque les peuples exaltaient les mérites de sa sainteté, il

commandait à quelque frère de lui lancer aux oreilles des paroles de nature à

l’avilir. Et quand le frère, bien malgré lui, l’appelait rustique, mercenaire,

maladroit et inutile, saint François tout égayé lui disait : « Que le Seigneur

vous bénisse, parce que vous dites les choses les plus vraies : elles sont

telles que je dois en entendre. » Le serviteur de Dieu ne voulut pas tant être

supérieur qu'inférieur, ni tant commander qu'obéir. Aussi il se démit du

généralat et demanda nu gardien à la volonté duquel il serait soumis en tout.

Il promit et pratiqua toujours l’obéissance à l’égard du frère avec lequel il

avait coutume d'aller.

Un frère ayant commis un

acte de désobéissance, en témoignait du repentir ; cependant l’homme de Dieu,

pour inspirer de la crainte aux autres, fit jeter le capuce de ce frère dans le

feu. Après que le capuce fut resté quelque temps, en plein foyer, il ordonna,

de l’ôter et de le rendre au frère. On ôte donc le capuce du milieu des

flammes, saris qu'il y eût la moindre trace de brûlure. — Un jour qu'il se

promenait dans les marais de Venise, il trouva une énorme multitude d'oiseaux

qui chantaient, et il dit à son compagnon : « Mes frères les oiseaux louent

leur Créateur, allons au milieu d'eux chanter les heures canoniales. » Quand il

pénétra dans cette volée, les oiseaux ne furent pas effrayés, mais le saint et

son compagnon ne pouvant s'entendre l’un l’autre à cause du gazouillement

excessif de ces animaux, François dit : « Mes frères les oiseaux, cessez de

chanter jusqu'à ce que nous ayons terminé notre office de Laudes. » Les oiseaux

se turent aussitôt, et quand les Laudes furent achevées, il leur donna la

permission de chanter et à l’instant ils continuèrent leur ramage comme à

l’ordinaire. — Il avait été invité par un chevalier auquel il dit : « Frère hôte,

suivez mes avis, et confessez vos péchés, car bientôt vous mangerez ailleurs. »

Le chevalier consentit; il régla ses affaires domestiques, et reçut une

pénitence salutaire. Or, comme ils entraient pour se mettre à table, l’hôte

mourut subitement. — Il avait rencontré une multitude d'oiseaux et il les avait

salués comme des créatures douées de raison. « Mes frères les oiseaux, leur

dit-il, vous devez beaucoup de louanges à votre Créateur qui vous a revêtus de

plumes; il vous a donné des ailes pour voler, il vous a départi les régions de

l’air et il vous gouverne sans aucune sollicitude de votre part. » Les oiseaux

se mirent alors à allonger le cou, à battre de l’aile, à ouvrir le bec et à

regarder le saint attentivement. En passant au milieu d'eux, il les touchait

avec sa robe et cependant aucun ne changea de place jusqu'à ce que leur en

ayant donné la permission, ils s'envolèrent tous à la fois. — Au château

d'Alviane, pendant une prédication, on ne pouvait l’entendre à cause: du

gazouillement des hirondelles dont le nid était proche. Et il leur dit : « Mes

soeurs les hirondelles, c'est à moi de parler maintenant ; vous avez assez dit

; gardez le silence jusqu'à ce que la parole du Seigneur soit achevée. »

Aussitôt elles lui obéirent et Se turent.

Un jour que l’homme de

Dieu voyageait dans la Pouille, il trouva sur le chemin une grande bourse

toute grosse d'argent. En la voyant, son compagnon voulut la prendre, pour en

faire largesse aux pauvres ; mais le saint s'y opposa formellement. « Il n'est

pas permis, dit-il, mon fils, de prendre le bien d'autrui. » Mais comme le

frère insistait fortement, François, après une courte oraison, lui commanda de

ramasser la bourse qui au lieu d'argent ne renfermait plus qu'une couleuvre. A

cette vue le frère eut peur, mais comme il voulait obéir et exécuter l’ordre

qu'il avait reçu, il prit la bourse avec les mains, et il en sortit un grand

serpent. Alors le saint dit : « L'argent, pour les serviteurs de Dieu, n'est

rien autre chose que diable et serpent venimeux. » — Un frère, fortement tenté,

se mit dans l’esprit que s'il avait sur lui quelque papier avec l’écriture du

saint, la tentation cesserait aussitôt. Mais comme il n'osait pas lui

manifester son désir, il arriva que l’homme de Dieu l’appela : « Apportez-moi,

lui dit-il, mon fils, du papier et de l’encre, car je veux écrire quelque chose

à la louange de. Dieu. » Et après avoir écrit, il dit: « Prenez ce papier et

gardez-le soigneusement jusqu'au jour de votre mort. » Et aussitôt toute

tentation s'éloigna de lui. — Ce même frère, lorsque le saint était malade, se

mit à penser : « Voilà que le Père est près de mourir, et ce serait pour moi

grande consolation, si; après sa mort, j'avais la tunique de mon Père. » Peu

après, saint François l’appelle et lui dit : « Je vous donne cette tunique et

après ma mort, elle vous appartiendra de plein droit. » — Il avait reçu

l’hospitalité à Alexandrie, en Lombardie, chez. un honnête homme, qui le pria,

pour observer l’évangile, de manger de tout ce qu'on servirait. Le saint ayant

consenti au pieux désir de son hôte, celui-ci courut lui préparer un chapon de

sept ans pour le repas. Pendant qu'ils étaient à table, un infidèle demanda

l’aumône pour l’amour de Dieu. Aussitôt le saint homme, entendant bénir le nom

de Dieu, fit passer au mendiant un morceau de chapon. Le malheureux infidèle

conserve. ce, qui vient de lui être donné, et le lendemain, tandis que le saint

prêchait, il le montre en disant : « Voici, quelle sorte de viande mange ce

frère que vous honorez comme un saint : c'est ce qu'il m’a donné

hier soir. » Mais. le morceau de chapon parut à tout le monde être du poisson.

Alors l’infidèle, traité d'insensé par toute l’assemblée, ayant appris ce qu'il

en était, resta confus et demanda pardon. Le morceau reparut être de la chair

quand le prévaricateur fut rentré en lui-même (Saint Antonin, tit.

XXIV, ch. II, § 2. — Wading). — Une fois que le saint était à table et

qu'il y avait conférence sur la pauvreté de la Bienheureuse Vierge et de son

Fils, aussitôt l’homme de Dieu quitta 1a table en poussant des sanglots de

douleur et couvert de larmes il mange sur la terre nue le morceau de pain qui

lui reste. — Il voulait qu'on témoignât une grande révérence pour les mains des

prêtres à qui a été confié le pouvoir de faire le sacrement du corps de N.-S.

Aussi disait-il souvent : « Si je rencontrais un saint venant du ciel et un

pauvre prêtre, j'irais au plus tôt embrasser les mains du prêtre, et je dirais

au saint « Attendez-moi, saint Laurent, parce que les mains que voici touchent

le verbe de vie, et elles possèdent quelque chose de surhumain. »

Sa vie fut illustrée par

de nombreux miracles. En effet, des pains qu'on lui présenta à bénir guérirent

beaucoup de malades; il changea de l’eau en vin, et un malade qui en goûta

récupéra aussitôt la santé, il fit encore beaucoup d'autres miracles. Quand il

approcha de sa fin, bien que réduit par une longue maladie, il se fit mettre

sur la terre nue et appela auprès de lui tous les frères qui se trouvaient dans

la maison. Imposant alors les mains sur eux tous, il les bénit, et, comme à la

Cène du Seigneur, il donna à chacun une petite bouchée de pain. Il invitait,

suivant la coutume, toutes les créatures à louer Dieu ; la mort elle-même, qui

est si terrible pour tous et si odieuse, il l’invitait aussi; il l’accueillit

avec joie, et la priait de venir en son hôtellerie, en disant : « Qu'elle

soit la bienvenue, ma sueur la mort. » Quand fut arrivée sa dernière heure, il

s'endormit dans le Seigneur. Un frère vit son âme, sous la forme d'une étoile

semblable à la lune en grandeur et brillante, comme le soleil. Le supérieur des

frères dans la terre de Labour, appelé Augustin, qui était à l’extrémité, et

qui avait déjà perdu depuis longtemps l’usage de la parole, s'écria subitement

: « Attendez-moi, père, attendez ; je vais avec vous. » Comme les frères lui

demandaient ce qu'il voulait dire, il répondit : « Ne voyez-vous pas notre père

François qui va au ciel? » Et, au même instant, il s'endormit en paix et suivit

le père. — Une dame qui avait été fort dévouée à saint François vint à mourir.

Les clercs et les prêtres étaient autour de sa bière pour ses funérailles,

quand tout à coup cette femme se lève sur le lit funèbre, et appelant un des

prêtres qui étaient là, elle lui dit :

« Mon frère, je veux me

confesser. J'étais morte et j'étais destinée à rester dans une dure prison,

parce que je n'avais pas encore confessé un péché que je vous découvrirai; mais

saint François ayant prié pour moi, il m’a été accordé de revenir à mon

corps, afin qu'après avoir déclaré ce péché, je pusse en obtenir le pardon. Et

je ne vous l’aurai pas plus tôt dit, que sous vos yeux je reposerai en paix. »

Elle se confessa donc, reçut l’absolution ; après quoi, elle s'endormit dans le

Seigneur. — Les frères de Vicéra demandèrent à un homme de leur

prêter son chariot; il répondit, tout indigné : « J'aimerais mieux écorcher,

deux d'entre vous et saint François en même temps, que de vous prêter mon

chariot. » Mais, rentré en lui-même, il se reprocha sa conduite et se repentit

de son blasphème, par la peur de la colère de Dieu. Peu après, son fils devint

malade et, fut réduit à l’extrémité. Quand il vit son fils mort, il se roulait

par terre, pleurait, et évoquait saint François, en disant : « C'est moi

qui ai péché, c'est moi que vous auriez dû frapper. Rendez, ô saint, à celui

qui vous supplie dévotement, ce que vous avez ravi à celui qui a blasphémé

indignement. » Bientôt, son fils ressuscita, et fit cesser ses pleurs, en

disant : « Quand je fus mort, saint François m’a mené par un chemin

long et obscur, jusqu'à ce, qu'il m’eût placé dans un verger des

plus beaux, et ensuite il m’a dit : « Retourne vers « ton père je ne

veux pas te retenir davantage. » — Un pauvre devait une certaine somme d'argent

à un riche, qu'il pria, pour l’amour de saint François, de proroger son terme.

Ce riche lui répondit avec orgueil : « Je t'enfermerai dans un endroit où

ni saint François, ni personne ne pourra t'aider. » Et aussitôt il fit enfermer

cet homme dans une prison obscure, après l’avoir enchaîné. Peu après, saint

François vint, brisa la prison, rompit les chaînes de cet homme et le ramena

sain et sauf à la maison. — Un soldat, qui se moquait des oeuvres de saint

François et de ses miracles, jouait un jour aux dés, et, rempli de folie et

d'incrédulité, il dit aux assistants : « Si François est saint, qu'il vienne un

coup de dix-huit. » Et aussitôt les trois des apportèrent le nombre six, et

jusqu'à neuf fois de suite; à chaque coup, il amena sur les trois dés le nombre